Apportionment: What Lies Beneath?

Apportionment: What Lies Beneath?

Federal Circuit remand of a $24 million damages award is a reminder that getting to the smallest salable unit is often not far enough.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit[1] issued the first substantive patent damages decision of 2018 with an important reminder: an apportionment methodology often needs to look deeper into the functionality of the accused product than the smallest salable unit to estimate the incremental benefit of the patent-in-suit.

In its decision to remand $24 million of the $39.5 million damages award in Finjan, Inc. v. Blue Coat Systems, Inc., the Federal Circuit rejected the damages opinion related to one of the patents-in-suit on the grounds that the methodology used did not apportion damages to the infringing functionality as is required. The Federal Circuit also took issue with the royalty rate used to measure this $24 million portion of the damages award, ruling that the rate was not supported by substantial evidence.

As we analyze this case, we also discuss two other interesting damages-related aspects of the Finjan opinion: the Federal Circuit allowed: 1) a simple fraction of allegedly infringing features from a list of product features to apportion the royalty base; and 2) damages in excess of the estimates offered by Finjan’s damages expert.

The decision also provides useful insight into the Federal Circuit’s approach to patent eligibility. However, our review herein only relates to the damages aspects of the opinion.

Case Law Background

A reasonable royalty in patent litigation has two primary components: the royalty rate and the royalty base (assuming a running royalty rather than a lump sum royalty). Once each is determined, the rate is multiplied against the base to determine the amount of compensation due to the patent holder for the infringement. In one approach, when the accused product contains multiple components and features, the revenue derived from the sale of the accused product is reduced to reflect only the revenue that relates to the patent(s) being asserted. In patent damages lingo, this process is referred to as apportionment and, in particular, apportioning the royalty base. Proper apportionment is important because, when evaluating the damages from the sale of a multicomponent product, an overly inclusive royalty base creates the risk of overcompensating the patent holder. As products become increasingly complex in terms of both the number of components and features, apportionment has become more difficult.

Under 35 U.S.C. Section 284, patent damages are set as those “adequate to compensate for the infringement.”[2] In the past decade, courts (including the Federal Circuit) have issued guidance, most often in the form of written opinions, on what damages experts need to consider. The Federal Circuit’s 2012 decision in LaserDynamics,[3] for example, limits the circumstances when the entire sales revenue of the accused product (the entire market value) can be used as the royalty base. Further, in 2014, the Federal Circuit ruled in VirnetX[4] that “the requirement that a patentee identify damages associated with the smallest salable patent-practicing unit [SSPPU] is simply a step toward meeting the requirement of apportionment.”[5] In cases where the SSPPU itself is a multicomponent apparatus with infringing and noninfringing features, “the patentee must do more to estimate what portion of the value of that product is attributable to the patented technology.”[6] And, a few months later, in Ericsson,[7] the Federal Circuit added, “The ultimate combination of royalty base and royalty rate must reflect the value attributable to the infringing features of the product, and no more.”[8]

Case Background

In August 2013, Finjan brought suit against Blue Coat in the Northern District of California, alleging patent infringement of six of its patents directed to identifying and protecting against malware. The infringing product is a cloud-based system for evaluating and categorizing websites, which is sold as one part of a suite of functionalities that make up a larger enterprise security system. The patents-in-suit were found to be directed to part of the cloud-based system for evaluating and categorizing websites.

After a trial, the jury found that Blue Coat infringed five of the asserted patents. The damages were awarded separately for each patent as follows:

$24,000,000 - '844 patent

$7,750,000 - ' 968 patent

$6,000,000 - '731 patent

$1,666,700 - '633 patent

$111,787 - '780 patent

Liability and damages issues related to the ’844, ’968, ’731, and ’633 patents were appealed to the Federal Circuit in 2016. The award relating to the ’780 patent was not appealed.

Damages Arguments ('844 patent)

Defendant's argument

On appeal, defendant Blue Coat argued against both the royalty base and royalty rate used to calculate the $24 million damages awarded for infringement of the ’844 patent.

As to the royalty base, Blue Coat argued that further apportionment was required to properly quantify the reasonable royalty damages directly attributable to the ’844 patent. Blue Coat argued that Finjan did not properly assess the incremental value associated with the patented invention because it did not properly assess the extent to which the defendant and its customers used the invention.

As to the royalty rate, Blue Coat argued that Finjan offered no substantial basis for the $8-per-user rate the jury used to calculate damages related to the ’844 patent. They argued that “$8 per unit is not a number that appears in any proposal, agreement or document in the record.”[9] Furthermore, Blue Coat argued that the sole evidence Finjan used to support this rate was testimony from Finjan’s own intellectual property (IP) licensing employee about an unrelated percentage rate derived from a 2008 verdict against a Blue Coat competitor in another lawsuit.

Plaintiff's argument

In defense of the royalty base, Finjan asserted that it satisfied the apportionment requirement relating to the ’844 patent because it calculated its royalty base by using the “smallest, identifiable technical component” of the accused product.

As to the royalty rate for the ’844 patent, Finjan maintained that the testimony from its vice president of IP licensing was sufficient to support the rate. Finjan also added that the rate was supported by the $14-$34 user fee Blue Coat charged for its products.

Federal Circuit ruling

In its ruling on damages related to the ’844 patent, the Federal Circuit agreed with Blue Coat, that the royalty base determination was not methodologically sound and the royalty rate was not properly supported.

In analyzing Finjan’s apportionment of the royalty base, the Federal Circuit found that further apportionment was necessary. While recognizing that Finjan may have identified “the smallest, identifiable technical component” for calculating the royalty base, the court ruled that having done so does not insulate Finjan from the “essential requirement” that the reasonable royalty award must be based on the incremental value of the patented invention.

The ruling made clear where Finjan’s apportionment theory fell short. WebPulse, the infringing product, is a cloud-based service that provides information about downloadables to a customer’s network gateway in order to help the gateway determine whether a particular downloadable can be accessed by a specific end user. All of the infringing functionality occurs in the Dynamic Real-Time Rating (DRTR) engine, which is a part of the accused WebPulse product. But some DRTR functions infringe, and some do not. Finjan attempted to tie the royalty base to the incremental value of the infringement by multiplying the number of WebPulse users by the percentage of traffic that passed through DRTR. However, DRTR also performed other noninfringing functions, and Finjan did not perform any further apportionment of the royalty base. The court stated that if the smallest salable unit contains noninfringing features, then the burden is on the party asserting damages to dig deeper, reiterating previous Federal Circuit decisions that it is a mistake to assume that there is no further constraint on the selection of the base once the smallest salable component is identified.

The Federal Circuit also agreed with Blue Coat that the $8-per-user royalty rate presented to the jury was not supported by the record. The court ruled that Finjan’s use of this rate failed on multiple fronts.

Specifically, Finjan:

-

Did not rely on any comparable license or negotiation that used or proposed an $8-per-user royalty rate

-

Failed to provide hard evidence or convincing testimony of how an 8%-16% rate derived from a verdict in another case related to an $8-per-user royalty rate in the present one

-

Failed to demonstrate how the technology at issue in the prior case related to that in the present case

-

Did not sufficiently explain how a royalty rate derived from a verdict in a separate case involving multiple patents applies to a single patent in the present case;

-

Incorrectly attempted to use a software user fee (the $14-$34 discussed above) to support a rate to license a patent

-

Presented contradictory evidence regarding what the $8-per-user rate represented. That is, on one hand, Finjan gave testimony that this is the current starting point in licensing negotiations, and on the other, Finjan stated this $8-per-user rate would have applied many years earlier during the hypothetical negotiation

Referencing these issues, the court’s opinion stated that the $8-per-user rate appeared to “have been plucked out of thin air,” and therefore could not be used as a basis for a reasonable royalty calculation.[10]

Based on the above, the Federal Circuit ruled that Finjan failed to present a case that could support the jury’s verdict with regard to the ’844 patent, and remanded for a determination of whether Finjan waived its right to establish reasonable royalty damages under a new theory and whether to order a new trial on damages.

Other Notable Aspects of the Decision

Our main takeaway from Finjan v. Blue Coat relates to the problems the court identified with the apportionment analysis surrounding the ’844 patent. The opinion, however, also provides some useful insight into how the Federal Circuit views the reliance on a technical expert to support a damages opinion and the court’s view of jury awards in excess of the damages amounts proffered by the experts at trial.

1. The court allowed a simple fraction of allegedly infringing features from a list of product features to apportion the royalty base under the assumption that each of the features was equally valuable.

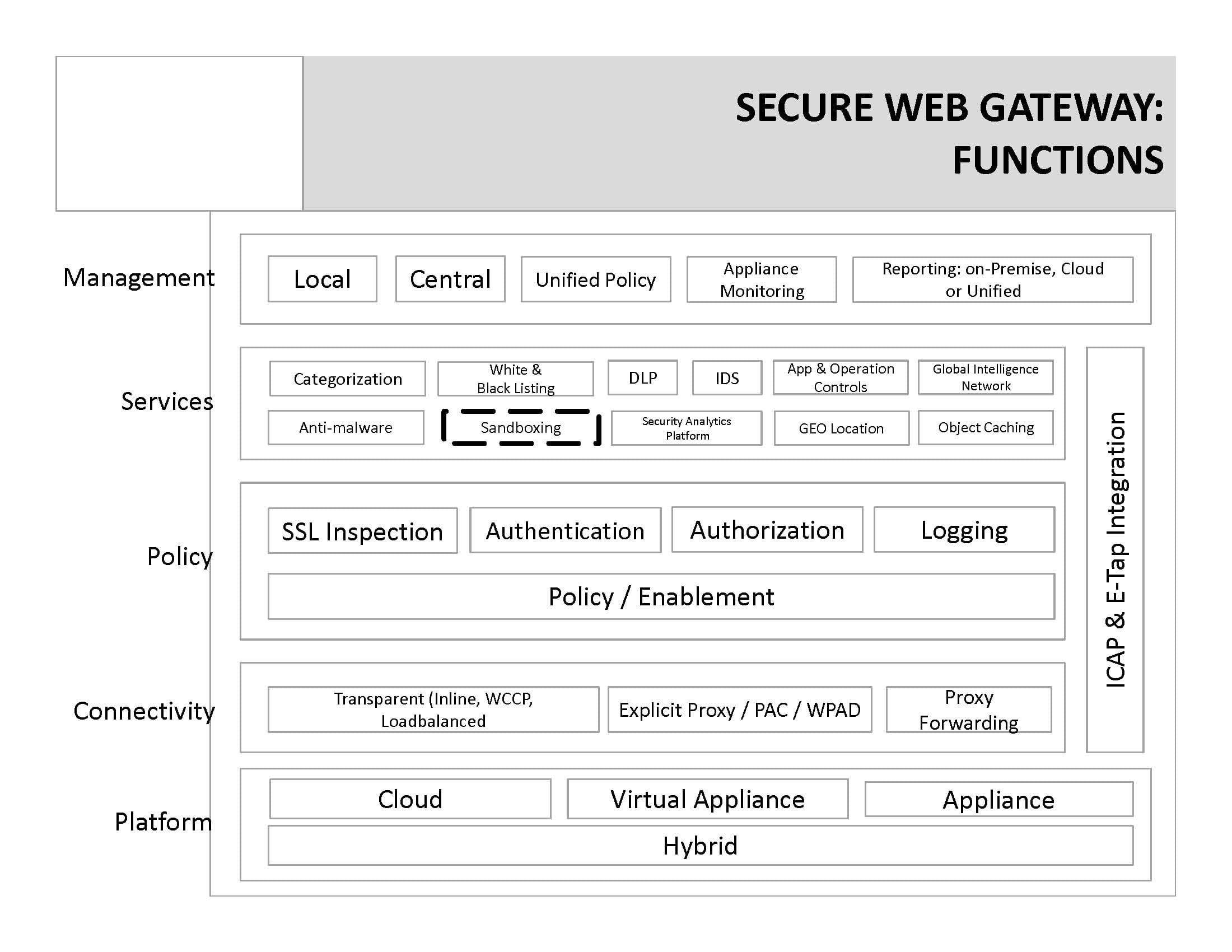

The court ruled that the royalty bases related to the ’731 and ’631 patents could be apportioned based on the fraction of the total number functions (as represented by boxes on a diagram) that infringed each of the patents respectively. The damages expert’s calculation assumed all the boxes/functions in the drawing were of equal importance. The plaintiff’s damages expert reached this understanding through discussions with Finjan’s technical expert as well as from testimony from a Blue Coat engineer, which purportedly confirmed the boxes/functions covered the full scope of the product. The diagram used is depicted here.

Because one function infringed the ’633 patent, and three infringed the ’731 patents, the expert used 1/24th apportionment for the ’633 patent and a 3/24th apportionment for the ’731 patent, which the court found acceptable.

2. The court allowed for damages in excess of the estimates offered by the plaintiff’s damages expert.

Finjan’s expert provided a range of damages for both the ’633 and ’731 patents. Finjan’s expert opined that the damages for the ’633 patent ranged between $833,350 and $1,111,133. The jury, however, awarded $1,666,700. As it related to the ’731, Finjan’s expert opined that the damages were between $2,979,805 and $3,973,073. The jury, however, awarded $6,000,000. The court allowed the awards, noting the expert’s estimates were conservative and that the underlying evidence could support the higher award.

Why Practitioners Need to Look Further

Lack of adequate support for the royalty rate aside, this ruling should remind us that the appearance of a superficial apportionment approach will struggle to withstand Federal Circuit scrutiny. Practitioners need to consider whether it is necessary to go further than the “smallest salable unit,” or, as Finjan submitted, “the smallest identifiable technical component,” to reasonably approximate the incremental value the invention adds to the end product. Through this decision, the Federal Circuit again informs us that incremental value of a patent is found in the value of the infringing functionality, especially when a component contains other important noninfringing functionality.

Co-authored by:

Scott Jones

Analyst - Dispute Consulting

+1.202.864.0378

sjones@stout.com

- CAFC or Federal Circuit or Fed. Circuit.

- 35 U.S.C. § 284.

- LaserDynamics, Inc. v. Quanta Computer, Inc., 694 F. 3d 51 - Court of Appeals, Federal Circuit 2012.

- VirnetX, Inc. v. Cisco Systems, Inc., 767 F. 3d 1308 - Court of Appeals, Federal Circuit 2014.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ericsson, Inc. v. D-Link Systems, Inc., 773 F. 3d 1201 - Court of Appeals, Federal Circuit 2014.

- Ibid. (emphasis added).

- Non-Confidential Brief of Appellant. Finjan, Inc. v. Blue Coat Systems, Inc. (December 20, 2016.)

- Ibid.