Considerations for Potential SPAC Acquirees

Considerations for Potential SPAC Acquirees

A boom in SPAC transactions is accompanied by a number of financial reporting and other considerations for acquisition targets.

A once seldom-used liquidity alternative, SPACs’ popularity has boomed in recent years. A SPAC, or a special purpose acquisition company, is a “blank check” company that raises money from investors through an initial public offering (IPO ) with the sole purpose of acquiring a target company that has not been identified at the time of the SPAC’s IPO. Around since the 1990s, SPACs began garnering greater attention between 2017 and 2019 before booming in 2020, due in part to volatility in the IPO market and increasing interest from sophisticated financial sponsors and management teams. Coupled with greater acceptance among the small and midsize private companies that have historically been SPAC targets, the momentum from 2020 has poured into 2021, with the influx of interest leading SPACs to begin outpacing traditional IPOs.

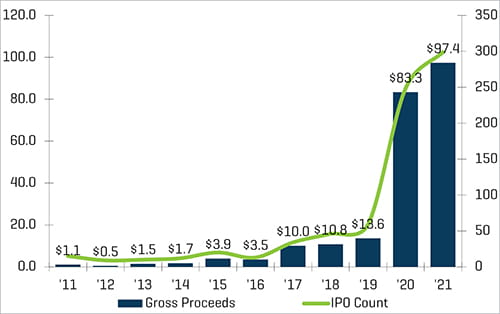

SPAC IPO Summary

Source: SPACInsider

2021 reflects year-to-date through 3/18/2021

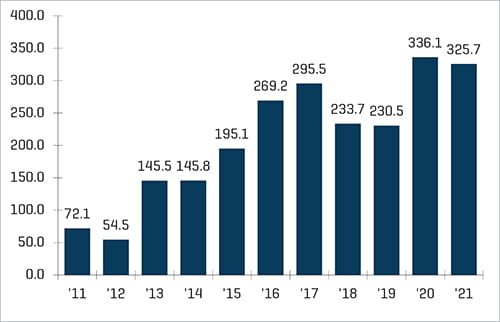

Average SPAC IPO Size

Source: SPACInsider

2021 reflects year-to-date through 3/18/2021

Expertise With Fair Value Measurement of SPACs

Life of a SPAC

The lifecycle of a SPAC includes its formation and IPO, search for a suitable acquisition target, vote by shareholders to approve the acquisition, and finally the merger with an acquisition target.

Formation and IPO

A SPAC is typically formed by an experienced management team or sponsor, who capitalize the SPAC by contributing nominal capital in exchange for founder shares that often comprise 20% of the shares of the company after the IPO, with the remaining interest held by public shareholders through units offered in the IPO. Each unit typically comprises one share of common stock plus a warrant to purchase a fraction of one share of common stock in the future. The warrants, intended to compensate holders for investing their capital in the SPAC before it acquires an operating company, become exercisable shortly after the SPAC acquires an operating company and are issued with a strike price that is out of the money (publicly traded shares are commonly priced at $10, with warrants maintaining an $11.50 strike price). Proceeds from the IPO are placed in a trust account until a future transaction is consummated or the SPAC is liquidated. Importantly, at the time of IPO, the SPAC cannot have identified an acquisition target and must also state in its registration statement that it has not identified any target.

Once formed, SPACs ultimately provide for a fixed 18 to 24 month period to identify and complete an initial business combination transaction. If it fails to do so, the SPAC must dissolve and return to investors their pro rata share of the assets in escrow.[1]

Target Search and Negotiation

After its formation and IPO, a SPAC has no other business purpose except to find a company to acquire or merge with. Similar to a typical merger and acquisition (M&A) transaction, the sponsor and management team will proceed to vet potential acquisition targets. Given the defined period to complete an acquisition, the due diligence process might move at an accelerated pace.

Shareholder Vote

Once a SPAC has identified and reached an agreement with an acquisition target, SPACs are typically required to send a proxy to shareholders (after filing with the SEC and responding to comments) before holding a shareholder meeting and corresponding vote. Importantly, when a SPAC proposes to acquire a specific target company, the SPAC’s public shareholders have the right to redeem their shares for a pro rata portion of the proceeds held in the trust account if they do not wish to invest in the proposed target (though the warrants received as part of each SPAC unit in the IPO remain outstanding regardless).

As a result of shareholder redemptions, it is possible that additional capital may be required to complete the transaction. Private investment in public equity (PIPE) deals involving affiliates of the sponsor or institutional investors purchasing common stock are a frequent source of capital in such situations. Other potential sources of capital include preferred equity investments from affiliates of the sponsors or institutional investors, the sale of additional common stock to public investors, or the issuance of debt.

Close of SPAC Merger

Upon the close of the SPAC merger (often referred to as “de-SPACing”), the sellers of the target company may receive cash, equity in the SPAC, or a combination thereof. In many cases, the sellers of the target company will retain some ownership in the merged entity. The post-merger combined entity moves forward as a publicly traded company.

Benefits to Acquirees

SPACs have garnered greater acceptance among companies of all sizes and across industries, and for good reason: SPACs offer a number of valuable benefits for the private companies they acquire.

- Quick execution: The SPAC planning and execution process might take five or six months for a target company, much faster compared with the potential 12 to 24 months to plan and execute a traditional IPO process. Going public through a SPAC may also be less expensive for a target company compared with a traditional IPO.

- Less volatility and uncertainty for target companies by locking in a price with the SPAC sponsor as part of a merger agreement. This avoids leaving money on the table by pricing an offering too low while also allowing target companies to negotiate valuation to account for nuances related to the business, such as tax attributes. SPACs become particularly attractive to target companies in times of high market volatility as they allow companies to avoid trying to time the market.

- Access to capital and liquidity, particularly for small and midsize companies that might not be traditional IPO candidates.

- Potential for seller to maintain upside by being paid in stock and / or retaining a significant interest in the target company post-transaction.

SPAC Readiness Considerations for Target Companies

Once a SPAC identifies a target, the SPAC then prepares a proxy statement to solicit shareholder approval for various aspects of the SPAC merger transaction. The financial statement requirements and related SEC review process for a SPAC transaction are largely consistent with the requirements for a traditional IPO.[2] As the SPAC merger process with a target company might be completed in as little as three to four months, a target company must accelerate public company readiness well in advance of any SPAC merger. In light of the compressed timeline, it is critical to engage a reputable advisor to efficiently and accurately assist in addressing key financial reporting and other public company readiness issues.

Unwinding Private Company Accounting Alternatives

While the targets of SPACs are usually privately held companies, they need to provide financial statements that comply with the form and content requirements of Regulation S-X and the U.S. GAAP requirements of a public business entity for use in the proxy statement. This may be particularly impactful for target companies that have historically elected private company accounting alternatives (“Accounting Alternatives”),[3] as they are required to retrospectively revise their financials from the date the Accounting Alternatives were elected before including them in a proxy statement.

- Recognition of Intangible Assets and Goodwill: Under the Accounting Alternatives, the recognition of non-competition agreements or customer-related intangible assets that are not capable of being sold or licensed independently from other assets of a business were not required to be recognized when performing an acquisition accounting valuation (commonly referred to as purchase price allocations) for a business combination. Rather, such value would have been subsumed into goodwill. In order to present public company-compliant financial statements, acquisition accounting valuation analyses[4] must be revised in order to determine the fair value of any previously un-recognized intangible assets. The recognition of such assets will also impact the amount of residual goodwill recognized in the business combination.

- Goodwill Impairment Testing: The Accounting Alternatives allow private companies to amortize goodwill on a straight-line basis over 10 years (or less) and avoid annual impairment tests (except when a triggering event occurs). This is in contrast with U.S. GAAP requirements, under which goodwill is an indefinite-lived asset and tested annually for goodwill impairment. In order to present public company-compliant financial statements, a company must not only unwind any goodwill amortization but also retrospectively perform annual goodwill impairment tests.This becomes particularly cumbersome when a target company is organized with multiple reporting units.

Unwinding the Accounting Alternatives can significantly increase the time needed to produce audited target company financial statements; thus, engaging a suitable valuation advisor is vital.

In addition, as a public company there are additional accounting issues (e.g., segment reporting, earnings-per-share) that will need to be addressed, documented, and reported.

Avoiding Cheap Stock Issues

Stock options and other forms of stock-based compensation are frequently issued to company officers and key employees in startup or early-stage companies in order to preserve cash and to align the incentives of key employees and investors. Commonly referred to as “cheap stock” issues, the SEC is on the lookout for stock-based compensation grants that are substantially below fair value in a pre-IPO period, as well as inadequate disclosures of the grant-date fair values. Target companies issuing stock-based compensation are well-served by coupling equity grants with a comprehensive valuation of the securities in order to meet financial reporting requirements in accordance with FASB ASC 718, to avoid any unintended IRC 409A tax consequences, and to avoid delays in the SPAC merger due to additional disclosures, restatements, and added professional fees.

Acquisition Accounting for the De-SPAC Merger

In addition to valuation-related work required for historical financial statements, de-SPACing itself may require substantial analysis, depending on whether the SPAC or the target company is determined to be the accounting acquirer in the transaction. Specifically, the accounting acquirer is the entity that has obtained control of the other entity, which might be different from the legal acquirer (which is generally the SPAC). If the target company is determined to be the accounting acquirer, the transaction will be treated similar to a capital raising event.[5] However, if the SPAC is determined to be the accounting acquirer, acquisition accounting in accordance with FASB ASC 805 will apply and the target company’s assets and liabilities will require a valuation to be stepped-up to fair value.[6] In determining the accounting acquirer, consideration should be given to the guidance detailed in ASC 805-10-55-11 through 55-15.

Public Company Readiness Assessment

After de-SPACing, the combined entity moves forward as a publicly-traded company subject to ongoing SEC reporting obligations. Early in its quest to be acquired by a SPAC, it is valuable for the target company to engage an advisor to determine whether the people, processes, and systems are in-place for the company to begin life as a public company. Key items to assess include (but are not limited to):

- Board of directors / governance

- Investor relations

- Budgeting and forecasting

- Financial reporting

- Internal controls and compliance with Sarbanes-Oxley Section 404, Section 302, and Section 906

- Treasury functions

Engaging an advisor to perform this assessment early in the SPAC pursuit will allow for a smoother process and provide ample time to remedy any areas that might need addressed in advance of becoming a public company.

Final Takeaways

SPACs offer a potentially quicker and cheaper path to the public markets for private operating companies while also avoiding stock market volatility. However, companies considering being acquired by a SPAC must keep in mind the substantial financial reporting requirements these companies must meet and the accelerated timeline upon which they must be met. Engaging an appropriate advisor will be critical to ensuring a smooth and successful transaction process.

- SPACs occasionally seek approval from shareholders to amend its charter documents to extend the acquisition deadline.

- Financial statements must comply with Regulation S-X, within which the SEC lays out the form and content of and requirements for financial statements.

- Accounting Alternatives include Financial Accounting Standards Board (“FASB”) Accounting Standard Update (“ASU”) 2014-02, Intangibles – Goodwill and Other (Topic 350): Accounting for Goodwill as well as FASB ASU 2014-18, Business Combinations (Topic 805).

- Per FASB Accounting Standards Codification (“ASC”) Topic 805, Business Combinations (“ASC 805”), and Topic 820, Fair Value Measurement (“ASC 820”).

- Also referred to as a reverse recapitalization.

- Also referred to as a forward merger.