The Impact of Tightening Debt Markets and Interest Deductibility Rules

The Impact of Tightening Debt Markets and Interest Deductibility Rules

After a succession of 2022 rate hikes by the Federal Reserve, unrelenting broad-based inflation, and the price of debt continuing to rise by the day, borrowers are having to adjust to a new normal. However, the new normal may entail more to navigate than just the higher interest rates.

If we set the “Wayback Machine” to 2017, the interest rate environment was markedly different, so much so that Congress enacted curbs on the tax benefits of debt for highly levered companies in the form of interest expense deduction limitations.

As part of the broader Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA), Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Section 163(j) was amended to place a limitation on the deductibility of interest that generally equaled 30% multiplied by Adjusted Taxable Income (ATI), effectively earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA). For this purpose, ATI is a company’s taxable income (Form 1120, Line 30), but adding back interest expense (Form 1120, Line 18), depreciation (Form 1120, Line 20), net operating loss (Form 1120, Line 29), and amortization (Form 4562). This limitation is calculated and reported on Form 8990, Limitation on Business Interest Expense Under Section 163(j).

There are also add backs for the Section 199A qualified business income deduction, non-trade or business losses or deductions, and certain other amounts. There are special rules applicable to partnerships and S corporations. There are reductions related to non-trade or business income or gain, business interest income (this prevents banks and financial institutions from having unintended limitations), and other items.

The 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) provided some taxpayer relief, increasing the 30% threshold to 50% for 2019 and 2020. For 2021, the threshold returned to 30%.

Even greater changes are currently underway for 2022 and future tax years. So now is a perfect time for financial sponsors and companies to dust off their old tax models because they will not be able to simply copy over the assumptions and formulas from last year.

For tax years starting January 1, 2022, the Section 163(j) rules became stricter, with the ATI limitation set at 30% of tax EBIT, rather than EBITDA. Without the benefit of the depreciation and amortization add back in the ATI calculation, many financial sponsors and their portfolio companies could find their interest expense deductions significantly limited in 2022.

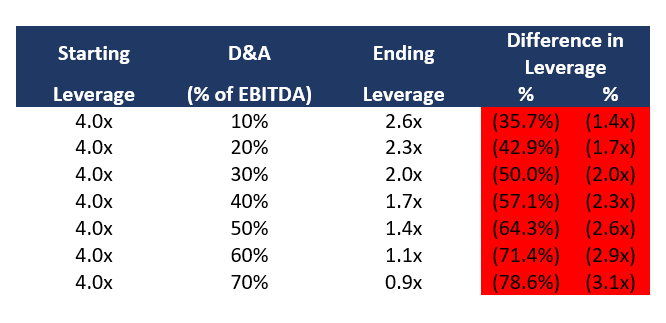

As an example, a company with $10 million of EBITDA that was paying 7.5% on its debt 12 months ago could have deducted up to $3 million of interest expense and supported up to $40 million of debt (4.0x leverage) with the full benefit of the tax shield. However, with rates now 300 basis points (bps) higher, that $40 million of debt would have an interest expense of $4.2 million, a full $1.2 million above the previously effective deductible tax shield ($3 million). Once you further reduce the denominator from EBITDA to EBIT, it amplifies the impact of the rate increase depending on the level of depreciation and amortization (D&A), as the effective deductible tax shield is impacted as follows:

Impact to Leverage – Sensitivity Analysis

As can be seen above, the impact will likely be much less severe for asset-light service companies, though any company with material tax amortization (e.g., portfolio companies that were acquired with a material tax basis step-up), may have interest expense tax deductibility issues to contend with. Regardless, the impact to the tax shield and corresponding leverage is meaningful, as even an asset light company with only 10% D&A would lose over a third of its tax shield.

This means that companies should review their estimated tax payments, tax provisions, and tax distribution calculations to ensure they are properly modeling the deductibility of their 2022 interest expense. Using the 2021 ATI rules could lead to companies underpaying their estimated federal or state income tax payments, overestimating after-tax cash flow, or failing to make sufficient tax distributions to partners.

There is still time to clean up these estimates and calculations before year end, including amending tax statements or making final estimated catch-up payments, as necessary. Companies should also keep an eye on Congress as we approach the end of the year, as there is still potential to provide some form of taxpayer relief from this stricter 2022 cap threshold.

This limitation will also apply to future tax years. Therefore, financial sponsors and their portfolio companies should be careful to model this increased limitation on interest deductibility into future estimates of cash taxes payable and factor this into their internal rate of return (IRR) analyses. For 2023 and future years, the limitation may have an even greater impact if interest expense increases either due to the terms of existing debt or new debt.

One small silver lining in this is the ability to carry forward unused interest expense deductions. In addition, on exit, the unused interest expense deductions carry forward similar to net operating losses (NOLs) and are also subject to the annual limitation rules of Sections 172 and 382. On exit, sellers may want to model the benefits of the interest expense carryforward to a buyer for purposes of requesting an increased valuation for the target. Buyers will be interested in modeling the potential benefit to determine what, if any, value the interest expense carryforward may hold, especially given the buyer’s own leverage considerations.

We note that these current rules are generally more restrictive than those in the European Union (EU). The interest expense limitation in the EU Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive (2016 ATAD) essentially limited interest deductibility to 30% of EBITDA, similar to the pre-2022 U.S. rules, but allowed member states the option to implement certain taxpayer relief mechanisms such as de minimis thresholds, escape clauses, and grandfathering provisions. The recent EU Debt-Equity Bias Reduction Allowance (DEBRA) directive proposes limiting the tax deductibility of interest expense to 85% of interest expense over interest income.

From a capital structure perspective, although subject to many commercial considerations, the combination of high interest rates, reduced interest deductibility, and future economic uncertainty may cause certain businesses to seek equity investments rather than take on new debt.

While great minds often think alike in making macroeconomic prognostications, every company needs to view its future outlook through the lens of its own unique facts and circumstances. This includes the ability to adapt to changing laws and regulations. However, unless Congress acts before year end to provide some relief, the tax headwinds described above will continue into 2023 and beyond. Companies should also keep an eye on the development of DEBRA in the EU, as the U.S. could be encouraged to follow suit in pursuit of an attempt at harmonizing global tax policies.