A Trade Creditor's Guide to Defending the "Wrong Payor" Fraudulent Transfer Case in Bankruptcy

A Trade Creditor's Guide to Defending the "Wrong Payor" Fraudulent Transfer Case in Bankruptcy

Consider the following hypothetical situation. One of your customers—we will call it “Debtor A”—is in significant financial trouble. You have done business with Debtor A for a long time, but lately Debtor A has fallen behind on its payments. The scuttlebutt is that Debtor A is about to file for bankruptcy. You receive a check on account of past due amounts owed by Debtor A. You notice the check is from Debtor B, which is a corporation affiliated with Debtor A. You count yourself lucky to be paid at all, and you deposit the check. You mark a red “X” on your calendar 90 days from the date the check cleared. If Debtor A holds off from filing bankruptcy until after that date, you think to yourself, you will be home free from a bankruptcy trustee avoiding that payment as a preference.

Happily, the 90-day period runs, and Debtor A and Debtor B file for bankruptcy 100 days after the check cleared. You sigh in relief, knowing you can rest easy because you cannot be sued on a preference.

To your surprise, two years later you are served with a complaint from Debtor B’s bankruptcy trustee. It does not allege a preference. Rather, it alleges a fraudulent transfer. The complaint alleges you invoiced Debtor A, your contract was with Debtor A, and the check from Debtor B paid for product that was delivered to Debtor A. All of this is true. The trustee’s complaint alleges that under these facts Debtor B did not receive “reasonably equivalent value” in exchange for Debtor B’s payment to you. Just when you thought you were home free, you find yourself embroiled in this “wrong payor” fraudulent transfer action.1

Introduction

While most credit managers and other professionals dealing with credit issues have encountered alleged preferential transfers, fraudulent transfer actions against trade creditors are not as common. One might assume that defending a fraudulent transfer is similar to defending an alleged preference, but it is a completely different statute—different elements, different defenses. This article explains defending wrong payor fraudulent transfer cases, offers guidance in defense strategy and analysis, and explores preventing these actions in the first place.

Avoidance Actions: A Brief Overview of Preferences and Fraudulent Transfers

A bankruptcy trustee2 can sue a creditor for payments that the creditor received prior to a debtor’s bankruptcy. This is known as the trustee’s “avoidance powers,” referring to the trustee’s power to avoid or “claw back” payments made to creditors by a debtor.

A trustee is empowered with a variety of avoidance actions. The most common is avoiding a payment as a “preference” under section 547 of title 11 of the United States Code (the “Bankruptcy Code”). In broad strokes, under section 547 all payments made by a debtor to a creditor in the 90 days prior to bankruptcy are presumed avoidable, unless the creditor can prove a defense. Important for purposes of this article, in order for a bankruptcy trustee to claw back a payment as a preference, section 547 requires the payment be “on account of antecedent debt owed by the debtor.” In other words, to be a preference, the debtor must have paid its own obligation.

But what if a debtor pays an obligation that is not its own obligation? What if, as in our opening example, the creditor provides the goods to Debtor A, invoices Debtor A, and then Debtor B pays the creditor? Under these facts, the payment could not be a preference under section 547; the statute requires that a payment must be “on account of antecedent debt owed by the debtor.” Rather, this payment by Debtor B appears on its face to be a payment on account of Debtor A’s obligation. The trustee will likely seek to claw back this payment as a fraudulent transfer under 548 of the Bankruptcy Code.

One important difference between preferences and fraudulent transfers is the scope of the payments potentially avoidable. While for preferences under section 547 of the Bankruptcy Code the trustee can seek to avoid payments made within the 90 days before bankruptcy, section 548 allows the trustee to avoid anything paid during the two years prior to bankruptcy. 11 U.S.C. § 548.

The Intentional Fraudulent Transfer

An intentional fraudulent transfer is one that the debtor makes with actual intent to defraud the creditors. 11 U.S.C. § 548(a)(1)(A). In an intentional fraudulent transfer case, the trustee must establish the debtor’s intent, which could be a difficult task for the trustee, who may not have easy access to the debtor or its records.

The Constructive Fraudulent Transfer

For a constructive fraudulent transfer, in contrast, the trustee must only establish that certain circumstances existed when the transfer was made, and it is not necessary for the trustee to establish the debtor’s intent. 11 U.S.C. § 548(a)(1)(B). The most common example of a constructive fraudulent transfer is one in which the debtor 1) received less than a reasonably equivalent value in exchange for the transfer and 2) was insolvent at the time the transfer was made. 11 U.S.C. § 548(a)(1)(B)(i), (ii). Under these “circumstances”—where the debtor receives less than reasonably equivalent value for a transfer made while insolvent—the Bankruptcy Code presumes that a transfer was fraudulent, and does not require the trustee to show the debtor’s intent.

Defending the Wrong Payor Fraudulent Transfer

There is no silver bullet to defend a wrong payor fraudulent transfer. Rather, the defense of these claims is highly fact-sensitive. The following is a summary of possible defenses and strategies.

The Best Defense Is a Good Offense: Taking the Fight to the Trustee on the Insolvency Element

Readers familiar with preference actions know that the bankruptcy trustee is required to establish that the debtor was insolvent at the time of the alleged preferential transfer. See 11 U.S.C. § 547(b)(3). For a 90-day preference action under section 547 of the Bankruptcy Code, the trustee enjoys a presumption that the debtor was insolvent at the time of the transfer. See 11 U.S.C. § 547(f). Insolvency is also an element of a constructive fraudulent transfer, see 11 U.S.C. § 548(a)(1)(B)(ii)(I), but in a fraudulent transfer action, as described below, it is much easier to attack the trustee’s case on insolvency.

Unlike a preference action, for a constructive fraud action there is no presumption of insolvency. That is, the trustee will have to affirmatively demonstrate and prove that the debtor was actually insolvent at the time of the allegedly fraudulent transfer. Both the proof of insolvency and the rebuttal are typically matters of opinion testimony most often provided by experts retained by the trustee and creditor. Much like the fraudulent transfer itself, an assessment of insolvency is unique and fact specific. Frequently, such analysis requires an intensive investigation of historical and expected financial performance of the debtor, an assessment of the balance sheet of the debtor (whether the value of assets exceeds the value of liabilities), and a determination of whether the business had adequate capital to continue to operate. While such an analysis can be complex, it can also significantly impact the case, as the proof of insolvency is a necessary fact for the trustee’s case to have merit. As such, the trustee’s retention of a qualified expert can have a significant impact on the case. Conversely, the defendant’s retention of a qualified expert to review the opinions and calculations put forth by the trustee can demonstrate that, in fact, the debtor was solvent at the time of the transfers.

In our example at the start of this article, we have two debtors: The transferor debtor (Debtor B, who paid an obligation of Debtor A) and the non-transferor debtor (Debtor A, whose obligation was paid). As discussed, one of the elements under the Bankruptcy Code is that Debtor B was insolvent at the time of the transfer. However, in addition to Debtor B’s solvency, Debtor A’s solvency could also be relevant. If Debtor A is solvent and wholly owned by Debtor B, any amount paid to Debtor A’s creditors increases the amount allocable to the owner of Debtor A—viz., Debtor B. Therefore, the argument would go, if Debtor A is solvent and Debtor B pays a certain sum to Debtor A’s creditors, the book value of equity held by Debtor B increases dollar-for-dollar, and thus a creditor, in this example, could assert that Debtor B received “reasonably equivalent value” in exchange for the payment to

a creditor.

First-Day Orders in Bankruptcy Regarding Cash Management

Corporate affiliates often employ some kind of centralized cash-management system. Continuing the Debtor A/Debtor B example, assume Debtor A is the operating company, and maintains its own bank accounts and receives cash from operations, and then Debtor A transfers or “upstreams” those funds to Debtor B.

One of the common “first day” motions in a chapter 11 bankruptcy case is a motion for authority to continue pre-bankruptcy cash-management practices. What if Debtor A and Debtor B file for bankruptcy as jointly administered cases, and ask the bankruptcy court to bless their cash-management practices? Does the bankruptcy court’s approval mean that pre-bankruptcy payments cannot be fraudulent? To the authors’ knowledge, only one reported case has dealt with this argument: In Collins & Airkman Corp. v. Valeo (In re Collins & Aikman Corp.), 401 B.R. 900 (Bankr. E.D. Mich. 2009), the defendants argued that the debtors’ first-day cash-management order prevented the debtors from going back and seeking to avoid as a fraudulent transfer the payments made by a non-operating debtor on behalf of an operating debtor.

The Collins & Aikman Case

The defendants in Collins & Aikman argued the doctrine of res judicata, which prevents a party from taking one position in litigation and then later taking a “clearly inconsistent” position. The defendants contended that the debtors could not argue at the beginning of the bankruptcy case (in the cash-management motion) that the cash-management system was important to preserving value and then argue (in the fraudulent transfer action) that payments made to these particular defendants according to that cash-management system were for less than reasonably equivalent value. Without ruling that a defense argument along these lines was per se invalid, the bankruptcy court rejected the defendants’ argument. The court held that the debtors’ representations in the cash-management motion related to debtors’ cash-management as a whole and debtors’ operations in the future, and that the allegations of fraudulent transfer against these particular defendants were not “clearly inconsistent” with the cash-management motion.

While the Collins & Aikman court rejected the res judicata argument in that case, the court may have found for the defendants if the facts were slightly different. If, for example, the cash-management motion made broader representations regarding the value of the debtors’ cash-management practices, or if the cash-management motion had referred specifically to payments to defendants, then the outcome could have been different. Creditors should keep this in mind when sued on a wrong payor fraudulent transfer, review closely any cash-management motions and orders, and determine whether they can make this defense argument work for them.

Indirect Benefit

While courts generally hold that a payment on behalf of a third party’s obligation provides no benefit to the paying debtor, some courts have recognized an exception referred to as the “indirect benefit” argument. An often-quoted case is Rubin v. Manufacturers Hanover Trust Co., 661 F.2d 979, 991-92 (2d Cir. 1981):

[A] debtor may sometimes receive “fair” consideration even though the consideration given for his property or obligation goes initially to a third person.. . . [A]lthough transfers solely for the benefit of third parties do not furnish fair consideration . . . the transaction’s benefit to the debtor need not be direct; it may come indirectly through benefit to a third person.

Id. at 991 (citations and internal quotation marks omitted). Determining the “indirect benefit” that the transferring debtor receives is highly fact-specific, and can arise in a variety of situations. In our continuing example, if Debtor A and Debtor B have a cash-management relationship such that Debtor A “upstreams” revenue from its operations to Debtor B, and Debtor B in turn pays Debtor A’s customers, such customers’ provision of goods or services to Debtor A surely provides an “indirect benefit” to Debtor B. See, e.g., Kovacs v. Hanson (In re Hanson), 373 B.R. 522 (Bankr. N.D. Ohio 2007). But “indirect benefit” can be found in much more complex transactions with multiple parties. See, e.g., Klein v. Tabatchnick, 610 F.2d 1043 (2d Cir. 1979) (fair consideration might exist for corporation’s grant of security interest in corporate property in exchange for secured party’s pledge of personal property as collateral for bank loan to majority stockholder, who loaned proceeds to corporation). The analysis of “indirect benefit” includes an assessment of what benefits may have been received (cash, collateral, rights, or perhaps simply time to continue to restructure in an effort to avoid bankruptcy). As such, it may be necessary to determine the value of such benefits. This, too, can be a challenging exercise in the case of benefits for which the value may not be intuitive or self-evident. Suffice it to say that in defending the “wrong payor” fraudulent transfer, a defendant should leave no stone unturned in looking for any potential benefit to the transferring debtors.3

Substance Over Form

“Substance over form” is a basic tenant of fraudulent transfer law. Boyer v. Crown Stock Dist., Inc., 587 F.3d 787, 792 (7th Cir. 2009). If the substance of the supposed “wrong payor” transaction does not appear to be fraudulent, a defendant likely has a strong argument against liability. This “substance over form” idea goes by many names: the step-transaction defense, the integrated-transaction defense, or the collapsing defense. Regardless of the name, it involves one central tenant: If the payment to the creditor by the debtor was merely a step in a larger transaction, and the larger transaction—when viewed as a whole—did not have a significant negative effect on the debtor, then the payment to the creditor was not fraudulent.

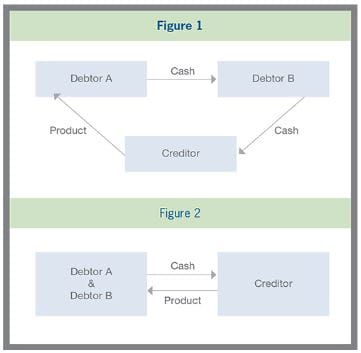

So, in our ongoing hypothetical, where Debtor B pays a customer of Debtor A, but Debtor B’s revenue is upstreamed to Debtor A [Figure 1], a court may “collapse” the transaction to its base: The creditor’s delivery of product to Debtor A/B, and Debtor A/B’s payment to the creditor on account of that product [Figure 2]. The following graphs illustrate this collapsing argument: Since in the collapsed transaction it is merely a case of a debtor paying a creditor on account of an obligation to the debtor, the argument would go, the creditor cannot be liable for a fraudulent transfer.

Good Faith/For Value Defense

The stand-by defenses to a preference action—ordinary course of business, ordinary business terms, and subsequent new value—are completely inapplicable in a fraudulent transfer case. However, there is a statutory defense available to a creditor-defendant faced with a wrong payor fraudulent transfer: The “good faith/for value” defense.

Section 548(c) of the Bankruptcy Code provides that a recipient of a constructively fraudulent transfer has a defense to the extent that the recipient took the payment “for value and in good faith”:

[A] transferee or obligee of [a fraudulent] transfer or obligation that takes for value and in good faith has a lien on or may retain any interest transferred or may enforce any obligation incurred, as the case may be, to the extent that such transferee or obligee gave value to the debtor in exchange for such transfer or obligation.

11 U.S.C. § 548(c).

The 548(c) defense requires both value and good faith. “Value” is broadly defined in the Bankruptcy Code as “property, or satisfaction or securing of a present or antecedent debt of the debtor.” 11 U.S.C. § 548(d)(2)(A). “Good faith” is notoriously hard to define. One way to describe it, however, is in the negative: That is, if the creditor knew or had reason to know of the debtor’s fraud, the creditor is not in good faith. Hayes v. Palm Seedlings Partners-A (In re Agric. Research & Tech. Group, Inc.), 916 F.2d 528, 535-36 (9th Cir. 1990). Knowledge of the debtor’s insolvency could prevent the creditor from being considered in good faith. Other courts have focused on whether there was anything to put the creditor on “inquiry notice” of the fraud, and whether the creditor reasonably followed up on the notice. Bayou Superfud LLC v. WAM Long/Short Fund II, L.P. (In re Bayou Group, LLC), 362 B.R. 624, 631 (Bankr. S.D.N.Y. 2007).

Conclusion

Defending the wrong payor fraudulent transfer is significantly different than defending a preference action. While there is no one-size-fits-all defense, the creditor that investigates the facts and knows the law has the best chance to fend off the trustee. The advice of experienced legal counsel and financial experts can assist in understanding the documents and information required to fully analyze the transactions at issue.

To prevent these issues from arising in the first place, a creditor should start with the businesspeople on the front lines of the credit relationships. The businesspeople should be aware of the potential issues of accepting a payment from a corporate entity different than that which appears on the creditor’s invoices or contract. While the parties at the time of doing business may be clear as to who is paying whom on whose behalf and why, a bankruptcy trustee years later may not understand the transaction from a cold read of the debtor’s records. The most important takeaway from this article should be the importance of documentation. Any document from the time of doing business that sets forth the understanding between the parties —even a simple e-mail between businesspeople—could be the basis for a bankruptcy trustee to walk away from a wrong payor fraudulent transfer. It is critical for credit managers and other credit businesspeople to understand these issues and document the transaction before customers run into financial trouble and file for bankruptcy.

Guest author:

Lucian B. Murley