Warning! The Service Believes S Corporations are Undervalued

Warning! The Service Believes S Corporations are Undervalued

The 1999 decision of Gross v. Commissioner (“Gross”) fundamentally changed the manner in which valuation experts and the Tax Court treat valuations of S corporations.1 In this decision, the Tax Court accepted a valuation that concluded that S corporation shares, due to the unique tax characteristics of S corporations, are inherently more valuable than C corporation shares.2

Prior to the Gross decision, valuation experts for both taxpayers and the Internal Revenue Service (the “Service”) typically valued S corporations using measurements of income that included a provision for corporate income taxes commonly referred to as “tax-affecting”.3 This treatment does not fully reflect the unique tax characteristics of S corporations when compared to C corporations.4 Since 1999, the Tax Court has been consistent in its rejection of this valuation practice. When confronted with the valuation of an S corporation, the Tax Court has accepted valuations which remove the “hypothetical” corporate income taxes from the analysis, thereby significantly increasing the appraised value of the S corporation; sometimes by as much as 60% or more.

Emboldened by Gross and subsequent decisions, the Service continues to challenge taxpayers submitting S corporation valuation reports which fail to properly address the tax-affecting issue. Augmenting their challenges is the failure of the valuation profession to reach a universal consensus on an appropriate methodology to capture an S corporation’s unique tax characteristics.

With well over four million S corporations in existence, the impact of this development has significant consequences.5 What is the validity of the Service’s position and how can taxpayers support their S corporation valuations?

Case Law and the Significance of the S Corporation Issue

Prior to the Gross decision, the Service, in its IRS Valuation Guide for appeals officers, stated that corporate income taxes should be included in S corporation valuations. Additionally, tax-affecting was specifically approved by the Tax Court in Estate of Hall v. Commissioner and Rudolph M. Maris v. Commissioner.6

At issue in Gross was a gift valuation of an approximately 1.9% interest in common stock of a soft drink bottling company. Consistent with prevailing valuation practices at time, the expert for the taxpayer tax-affected the company’s earnings. The expert for the Service, however, argued that tax affecting was inappropriate since the company, as an S corporation, does not pay corporate taxes. In addition, there was no evidence presented that the company would cease to continue as an S corporation, and the company historically distributed 100% of earnings.

At trial, the Tax Court considered valuation opinion reports prepared by experts for the taxpayer and the Service. Based on the evidence presented, the Tax Court concluded that simplistic tax-affecting of the earnings of the company was not a reasonable approach to the analysis. Consequently, the Tax Court accepted the valuation proposed by the Service, which eliminated tax-affecting from the analysis, and concluded a substantially higher indication of value.

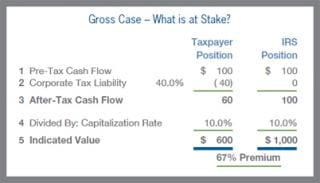

The impact of not tax affecting, given current and expected corporate tax rates, can be dramatic as illustrated in the hypothetical example below:

Subsequent to Gross, the Tax Court again raised the S corporation tax-affecting issue in the 2001 Wall v. Commissioner decision.7 Unlike Gross, the Tax Court found fault with both experts and ultimately accepted the Service’s original statutory deficiency notice while concluding that the taxpayer had not adequately supported the use of pretax P/E multiples (essentially a tax-affecting analysis) as a reasonable means to address the S corporation tax-affecting issue. Specifically, the Tax Court noted that “because this methodology attributes no value to . . . S Corporation status, we believe it is likely to result in an undervaluation of . . . stock.”

Unlike Gross and Wall, in the 2002 case of Heck v. Commissioner, the Service’s position against tax-affecting was accepted by both experts.8 Interestingly, the Service’s expert applied a 10% discount for lack of control which it believed incorporated the “additional risks associated with S corporations.” The Tax Court, by accepting this analysis, effectively incorporated a significant premium in value for the company’s status as an S corporation while mitigating it slightly with a small discount.

The 2002 case of Estate of William G. Adams, Jr. v. Commissioner extended the application of an S corporation premium to that of a controlling interest.9 Adams is also notable in that, while not discretely applying a reduction to cash flows for hypothetical corporate income taxes, the taxpayer’s expert increased the discount rates applicable to the company’s income. As discount rates are derived from transactions in securities of tax-paying entities (C corporations), they produce after-tax rates of return. The taxpayer’s expert increased the discount rates to a pre-tax rate of return. The expert reasoned that a pre-tax discount rate could be appropriately applied to the pre-tax cash flows of the company. In citing Gross, the Tax Court found the analysis to be an improper means to essentially tax-affect the earnings of the S corporation.

In the 2006 Robert Dallas v. Commissioner matter, the valuation experts for the taxpayer tax-affected the company’s earnings while the expert for the Service did not.10 However, the taxpayer’s experts attempted to distinguish this situation from Gross on the basis that the corporation in Gross distributed virtually all its income to shareholders while the company in Dallas distributed only an amount necessary to satisfy the shareholder pass-through tax liabilities. As such, the distribution of approximately 100% of income results in returns to shareholders over-and-above that of the associated tax liabilities. In contrast, distributions to shareholders that are less than the associated tax obligation results in no such return to shareholders. In rejecting this reasoning, the Tax Court indicated that the Gross treatment of tax-affecting “is independent of the proportion of earnings distributed.”

Accordingly, since 1999, the Tax Court has consistently:

- been presented with improper valuation models that do not adequately address the unique tax attributes of S corporations;

- rejected the simplistic application of hypothetical corporate taxes to the income of S corporations, thus concluding a significant valuation premium;

- recognized that certain tax characteristics of S corporations are detrimental which may mitigate the corporate and shareholder tax benefits;

- concluded that a tax-affecting valuation premium for S corporations applies to both minority and controlling equity interests; and

- disallowed efforts to effectively tax affect an S corporation’s income by arbitrarily adjusting discount rates or pricing multiples

Determining a Reasonable Adjustment

Any adjustment to the valuation of an S corporation relative to a C corporation must first recognize the fact that S corporation shareholders do not avoid taxation, but rather avoid a second layer of taxation on the dividends and capital appreciation of their ownership interest. Since the Tax Court has not been presented with a valid S corporation model in any of its decisions, it has been unable to properly consider the valuation related tax differences between S corporations, C corporations, and their respective shareholders. It is our view that if the Tax Court had been presented with a valid S corporation model, the concluded indications of value would likely have been substantially lower.

We understand the reasoning of the Tax Court given the evidence presented at various trials, however, when the valuation of an S corporation excludes any form of tax-affecting, the indications of value become so large that they begin to violate economic principles related to the cost of conversion of a C corporation to an S corporation. In other words, at valuation premiums implied by not tax-affecting, investors would constantly be asking themselves “why would I pay 66% more for an S corporation than a C corporation, when I could buy a C corporation and convert it to an S corporation for much less?”

The cost of a C-to-S conversion typically includes explicit costs (e.g., legal fees, accounting fees, valuation expert fees, etc.) and implicit costs (e.g., higher cost of capital, inherent tax liabilities associated with the recognition period, limitation on shareholders, etc.). Typically these costs would not approach the costs reflected by the level of premiums suggested by relevant Tax Court decisions. In addition, if a 60% valuation premium was available to qualified C corporations by conversion to an S corporation, an arbitrage opportunity would exist to maximize shareholder value by conducting C-to-S conversions. The trend towards pass-through entities as the preferred corporate organizational form is undeniable; however, C corporations have not converted en masse to avail themselves of such an opportunity. The anecdotal evidence suggests that the valuation premiums reflected in relevant Tax Court decisions are overstated.

The S Corporation Economic Adjustment Model

One valuation model that has gained widespread usage, credibility, and acceptance is the S Corporation Economic Adjustment Model (“SEAM”), developed by Daniel R. Van Vleet, ASA, of Stout Risius Ross, Inc.11

When using the SEAM, analysts first value the S corporation at its C corporation equivalent value. This is important since the discount rate used in the Discounted Cash Flow Method and the P/E multiples used in the Guideline Public Company Method are derived from publicly traded C corporations. Consequently the proper application of these methods requires that the earnings used to estimate S Corporation value are also on a C corporation equivalent basis. However, as properly noted by relevant Tax Court decisions, this type of analysis is simplistic, incomplete, and does not properly reflect the differences in tax attributes between S corporations, C corporations, and their respective shareholders. The SEAM is based on these tax differences and is used to adjust a C corporation equivalent value to an S corporation value. When properly conducted using current tax rates, the SEAM adjustment is typically in the 10% to 20% range over the C corporation equivalent value. This adjustment is significantly less than the 60%+ premiums suggested by various Tax Court decisions.

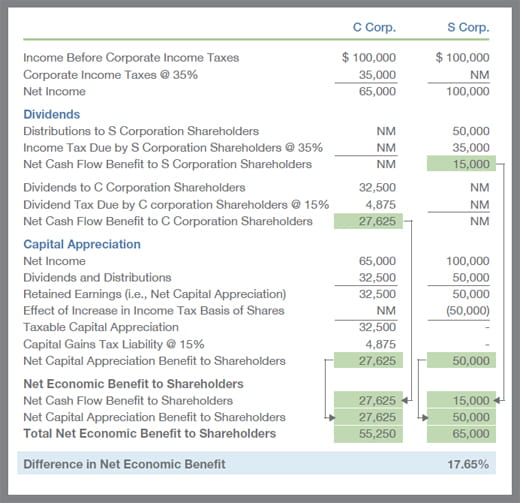

The following table provides an illustrative example of the components of the SEAM and the differences in economic benefits at the shareholder level between S corporations, C corporations, and their respective shareholders. The table was prepared using the income tax rate assumptions below:

- C corporation effective income tax rate of 35%;

- Individual ordinary income tax rate of 35%;

- Capital gains tax rate of 15%; and

- Income tax rate on dividends of 15%.

The table illustrates the income tax-related differences between C corporations, S corporations, and their respective shareholders and reflects the foundational basis of the SEAM. As demonstrated, the net economic benefit derived by S corporation shareholders is 17.65% greater than the net economic benefit derived by C corporation shareholders under the selected tax rate assumptions. In this example, the SEAM would increase the C corporation equivalent value of equity by 17.65%. As discussed, this adjustment is significantly lower than the 60%+ premiums suggested by relevant Tax Court matters.

In addition to the application of the SEAM, analysts should also consider the unique risk characteristics of S corporations vis-à-vis C corporations, including the following:

- loss of S corporation status due to an involuntary revocation for violations of IRS regulations,

- distributions by S corporations that are insufficient to pay for the shareholder pass-through income tax obligations,

- maximum number of shareholders limited to 100,

- prohibition against foreign ownership,

- prohibition of ownership by a C corporation,

- inability to become publicly traded without conversion to a C corporation,

- inability to create different classes of stock other than voting and nonvoting,

- changes in the ordinary income tax rate, and

- requirement that all shareholders consent to certain corporate transaction structuring events.

These factors may have an impact on the desirability of an S corporation equity security when compared to an identical C corporation equity security. A comprehensive valuation analysis of an S corporation should consider these differences and incorporate them into the analysis.

Conclusion

So far, the Tax Court has not been presented with a valid S corporation valuation model that properly addresses the unique tax attributes of S corporations. Consequently, the Tax Court has rendered its opinions based on the decision to simplistically “tax-affect” or “not tax-affect”. Unfortunately, when conducted in isolation, both tax-affecting and not tax-affecting are equally wrong. A proper S corporation valuation analysis will consider all the tax attribute differences between S corporations, C corporations, and their respective shareholders and adjust the value accordingly. The SEAM is an S corporation model that considers and properly reflects these differences.

The Service is becoming increasingly aggressive with taxpayers that fail to properly address the tax-affecting issue in their valuations of S corporations. It is important for any valuation of an S corporation to include specific adjustments that explicitly reflect the significant tax differences between S corporations and C corporations. Failure to do so may expose the owners of S corporations to a “red flag” audit issue with the Service. In addition, a valuation analysis that fails to consider these important tax differences would be correct only by coincidence.

Daniel R. Van Vleet, ASA

1 Gross v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 1999-254, affd. 272 F.3d 333 (6th Cir. 2001).

2 Because the tax attributes of pass-through entities are consistent in lacking the applicability of Federal corporate income taxes, the article utilizes the terms “S corporation” and “shareholder” to refer to pass-through entities and their owners in general.

3 “Tax affecting” is deducting hypothetical, corporate-level taxes in valuation models when no such legal obligation exists.

4 Unlike C Corporations, S corporations are not subject to federal income taxes at the entity level. Also, the distributions (i.e., dividends) of S corporations are generally not taxable and the capital appreciation of the stock is not taxable to the extent it is attributable to the retained earnings of the corporation. On the other hand, C corporation shareholders pay taxes on dividends upon receipt and capital gains upon sale of their stock. Also, unlike C corporations, the shareholders of S corporations report their pro-rata share of the income of the corporation on their personal tax returns and pay the taxes accordingly.

5 Statistics of Income, Internal Revenue Service, http://www.irs.gov/uac/Tax-Stats-2

6 Hall, T.C. Memo 1975-41. Maris, T.C. Memo 1980-144.

7 John E. Wall v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo 2001-75.

8 Heck v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2002-34.

9 Adams v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2002-80.

10 Robert Dallas v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo 2006-212.

11 “The Van Vleet Model”, Business Valuation & Taxes: Procedure, Law & Perspective, edited by Shannon P. Pratt and U.S. Tax Court Judge David Laro, 1st ed., New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2005.