How to Properly Capitalize Subsidiaries Without Getting Ensnared in the Earnings-Stripping Rules

How to Properly Capitalize Subsidiaries Without Getting Ensnared in the Earnings-Stripping Rules

The earnings stripping rules for MNOs certainly can be daunting; here are some ways to resolve key issues.

When multinational organizations (“MNOs”) create an entity overseas, they fund the new enterprise with debt and equity. Typically, financing primarily with debt is preferable because the new foreign subsidiary gets a tax deduction for the interest, and the payment allows the parent to immediately get its money back via interest charges. Debt used for financing is often in the form of an intercompany loan.

Taxing jurisdictions create thin capitalization (debt-to-equity) limits of 2-1, 3-1, etc., to prevent companies from overleveraging subsidiaries or stripping out the untaxed earnings.1 These limits prevent interest from being a disguised dividend (post-tax) remuneration to the parent company.

Once the debt-to-equity ratio is surpassed, the subsidiary cannot deduct the interest under the debt limit rules. In addition, typically the parent company must record the related interest income. In essence, the multinational organization is whipsawed, and to make the leverage breach even more unpalatable, the interest deduction disallowance could be permanently re-characterized as a deemed dividend.2

Recently, various taxing jurisdictions have addressed earnings stripping. Most notable among them is the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (“OECD”), which issued a report in February 2013 that provides 15 action items regarding base erosion and profit shifting (“BEPS”) and related topics. Action item number 4, on debt, actually suggests two actions: development of earnings stripping guidance for local interest deduction rules and development of transfer pricing guidance for related party transactions.3

This article addresses the background of thin capitalization, proposes ways to create proper intercompany documentation and identifies practical ways to resolve thin capitalization issues at different points of MNOs’ organizational life cycles.

Background of thin capitalization

Typically, U.S. based enterprises with foreign parent corporations cannot deduct interest paid to foreign related parties in excess of a 1.5-to-1 debt-to-equity ratio.4 Other countries impose similar restrictions on deducting intercompany interest. It is important to note, however, that these restrictions often do not apply to debt payable to a third party.5 The purpose of the thin capitalization rules is to prevent MNO’s from using intercompany debt to reduce taxable income and/or remove pre-tax profits in the form of interest rather than a dividend.

MNOs that have a group guarantee of third-party debt that includes a foreign parent are sometimes subject to the thin capitalization rules even though they do not have significant intercompany debt. Interest paid to a third party is subject to the thin capitalization rules because of this disqualifying guarantee.6

Intercompany documentation

Because thin capitalization relates primarily to intercompany debt, not third-party loans, it is necessary for MNOs to set up and maintain proper intercompany documentation for transfer pricing purposes. As previously mentioned, action item number 4 of BEPS draws the correlation between earnings stripping and transfer pricing. This is particularly applicable to true cross-border transactions.

Under the transfer pricing rules, it is necessary to set up intercompany documentation. The U.S. Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) states in the Internal Revenue Code (“IRC”) Section 482 regulations that a taxpayer should consider “all relevant factors,” including “the principal amount and duration of the loan, the security involved, the credit standing of the borrower, and the interest rate prevailing at the situs of the lender or creditor for comparable loans between unrelated parties.”7

Other countries have similar documentation requirements. For example, in its Taxation Ruling 92/11, the Australian Taxation Office cites the following factors, among others:

- The nature and purpose of the loan

- The market conditions at the time the loan was granted

- The amount, duration and terms of the loan

- The currency in which the loan was provided, and the currency in which repayment has to be made

- The security offered by the borrower

- Guarantees involved in the loan

- The credit standing of the borrower

- The situs of the lender and the borrower

- The prevailing interest rates for comparable loans8

In addition to IRC Section 482 and currently the subject of proposed regulations is IRC Section 385. Congress enacted IRC Section 385 in 1969, giving the IRS the power to determine whether intercompany loans are, in substance, equity investments. Tax authorities believed that characterizing intercompany loans as equity would resolve the thin capitalization issue.9

There is no question that the IRC Section 385 rules are complex and that guidance to taxpayers over the years on Section 385 has been nothing more than a large body of case law that prescribes criteria of what is intercompany debt versus equity. To address these challenges, the IRS recently issued proposed IRC Section 385 regulations that grant the IRS stronger regulatory powers to recast intercompany debt as equity.10 These proposed regulations require that intercompany debt should be acknowledged only if the exchange is for cash or other non-stock property that increases the non-stock gross assets of the issuer.

Resolutions to thin capitalization issues

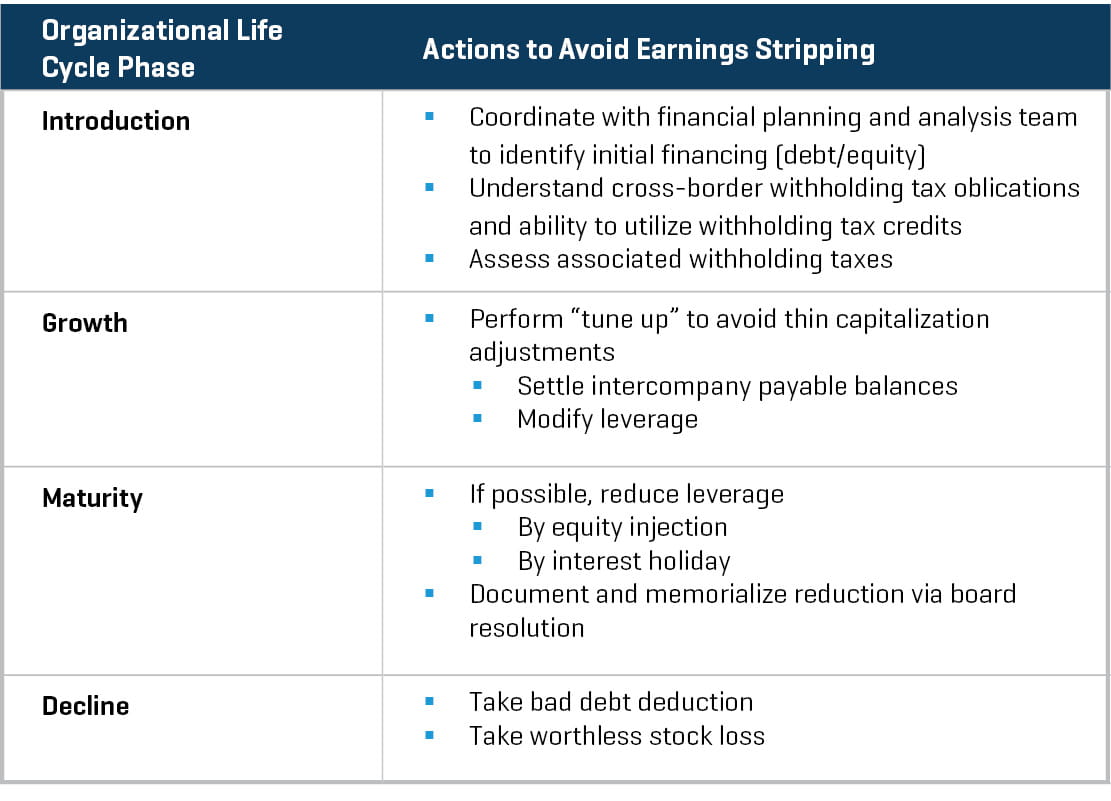

The appropriate resolution method depends on where an entity is in its organizational life cycle. According to Larry E. Greiner, the organizational life cycle comprises four phases: Introduction, Growth, Maturity and Decline.11 Thin capitalization is resolved differently in each of the phases.

Introduction

During this phase, consider the following factors:

- Initial Financing – Is the capitalized entity expected to be profitable within the next few years? It might be necessary to contact the organization’s financial planning and analysis team to determine how much sense it would make to add leverage to a subsidiary that is not expected to be profitable soon.

- Cross-Border Withholding Tax Obligations – Do the jurisdictions involved have the same withholding tax obligations? The IRC states that the withholding tax on U.S. source interest is 30% unless reduced by a tax treaty.12

- Associated Withholding Taxes – Does it make sense to capitalize a company with debt and then pay the associated withholding taxes on interest if the subsidiary does not have the capacity to pay the debt? If the answer is no, it might make sense to capitalize the entity primarily with equity.

Growth

Once the enterprise is up and running and presumably in the Growth phase, it is necessary to review the capitalization structure. Assuming the subsidiary has been financed with debt, the financing structure might require a “tune up,” including settling intercompany payable balances and modifying leverage based on expected business performance. A tune-up could prevent the enterprise from breaching the thin capitalization ratios.

Maturity

During the Maturity phase, it might be necessary to reduce leverage in order to avoid being subject to the earnings stripping rules. One common practice is for the parent company to make an equity injection into the subsidiary, thereby converting the debt-to-equity ratio and reducing the interest burden. A second method of reducing leverage is to grant the subsidiary an interest holiday for a short period of time. When taking either action, be sure to properly document and memorialize it in a board of director’s resolution.

Decline

The final – and oftentimes most difficult phase is Decline. If the subsidiary is likely to be closed, it might be a good time to determine whether the parent company can take a bad debt deduction on the intercompany debt.13

Alternatively, an enterprise might want to assess whether it makes sense to take a worthless stock loss of the subsidiary.14 Numerous indicia (e.g., an identifiable event, insolvency, lack of future value) determine whether a worthless stock loss is indeed an ordinary business loss or a capital loss.15 Pay careful attention to how the transaction is handled, because if a majority of the IRC Section 165(g) criteria regarding taking the loss are not met, such loss might be re-characterized as a capital loss or disallowed altogether.

Conclusion

The earnings stripping rules for MNOs certainly can be daunting. When MNOs manage the rules properly, however, the U.S. offers a fairly generous debt-to-equity ratio, allowing U.S. issuers of debt to offset 50% (1.5-to-1 ratio) of taxable income with interest. By working with internal partners in the enterprise, MNOs can gain a deep understanding of where their subsidiaries are in the organizational life cycle. Once MNOs know which phase their subsidiaries are in, tax practitioners can take appropriate proactive measures — including balance sheet cleanup, proper leverage, equity injections and interest holidays to mitigate the impact of thin capitalization. Alternatively, if the subsidiaries are in decline, MNOs can minimize the pain of the loss by taking a bad debt deduction or worthless stock loss.

Contact the author:

John P. Garcia

john.garcia@cpa.com

- Von Brocke, K., and E. Perez, “Group Financing: From Thin Capitalization to Interest Deduction Limitation Rules,” International Transfer Pricing Journal (Jan./Feb. 2009), 29-35.

- Under Section 247 of its Income Tax Act (“ITA”), Canada generally denies the deduction by a corporation resident in Canada (“CRIC”) of interest payable to specified nonresidents (i.e., nonresidents who own shares representing more than 25% of the votes or value of the CRIC, or nonresidents who do not deal at arm’s length with such shareholders), to the extent that a CRIC exceeds the revised 1.5-to-1 debt-to-equity ratio. Effective as of tax year 2013, the thin capital rules in the ITA extend to the debt of Canadian branches of nonresident corporations. Further, any disallowed interest under the thin capitalization rules is deemed a dividend for Canadian withholding tax purposes. The dividend is considered paid to the nonresident at the time the recharacterized interest amount is paid (or at year-end, to the extent of the unpaid portion of interest at year-end).

- Collier, Richard; Greenfield, Phil; van Weeghel, Stef; Olson, Parn; and Moens, Bernard, “OECD Heading Toward Consensus on Interest Limitation Rules (BEPS Action 4),” Journal of International Taxation 26.10 (Oct 2015): 23-24.

- IRC Section 163(j)(1)(A); IRC Section 163(j)(3)(A); and IRC Section 163(j)(2)(A)(ii).

- IRC Proposed Regulation Section 1.163(j)(1).

- IRC Section 163(j)(3)(B)(i).

- IRC Regulation Section 1.482-2(a)(2)(i).

- Australian Taxation Office, Taxation Ruling 92/11, Paragraph 83 (3 Transfer Pricing Report 442, Aug. 3, 1994).

- Stuart Webber, “Thin Capitalization and Interest Deduction Rules: A Worldwide Survey,” Tax Notes International (November 29, 2010), 683.

- John D. McDonald, Stewart R. Lipeles, and Samuel Pollack, “International Tax Watch: Treasury Releases Game Changing Code Sec. 385 Regulations,” Taxes (June 2016), 11-40, 75-76.

- Larry E. Greiner, “Evolution and Revolution as Organizations Grow,” Harvard Business Review 50 (July-August 1972), 37-46; and Robert E. Quinn and Kim Cameron, “Organizational Life Cycles and Shifting Criteria of Effectiveness: Some Preliminary.”

- IRC Section 1442(a).

- IRC Section 166.

- IRC Section 165(g)(3).

- Jerred G. Blanchard, Jr., Debra J. Bennett, and Christopher D. Speer, “The Deductibility of Investments in Financially Troubled Subsidiaries and Related Federal Income Tax Considerations,” The Tax Magazine, 2002.