A Primer for Equity Award Modifications Within a Downturn

A Primer for Equity Award Modifications Within a Downturn

As companies grapple with the current economic slowdown, they may elect to make changes to their executive compensation and incentive plans in order to drive retention and motivate senior executives to drive results for the business.

Changes such as these can be wide-ranging, from the elimination of executive incentive programs and bonuses and salary deferrals to the acceleration of year-end bonuses or special one-time payments to non-executives. Another change includes the disclosing of adjustments to existing employee stock-based compensation awards. Adjustments like these may gain momentum in the marketplace as reporting entities seek to balance supporting employees in the short term while continuing to incentivize long-term performance.

Modifications can take the form of repricings, where the exercise price is reduced, or more complex exchange programs, whereby companies modify more than just the exercise price. Most commonly, this involves amending the performance and market conditions upon which awards vest.

What Constitutes a Modification?

Accounting Standards Codification Topic 718, Compensation – Stock Compensation (ASC 718), defines a modification as “a change in the terms or conditions of a share-based payment award.” This definition is applied broadly and typically includes situations in which awards are canceled and replacement awards are issued. Modification accounting is not required if all of the following are unchanged immediately pre- and post-modification:

- The fair value1 of the award

- The vesting conditions of the award

- The classification of the award (e.g., equity or liability)

Examples of changes to employee equity that we have seen classified as a modification under this guidance include:

- A reduction in equity award exercise price

- A change in the contractual exercise term of an award

- An adjustment to vesting criteria, such as (i) a reduction in financial metric targets that impacts vesting or (ii) a reduction to stock price target thresholds related to vesting

- A reduction of the exercise price of an award due to a one-time dividend (in a manner not contemplated in the original award agreement)

- The addition or subtraction of companies from a competitor peer group that impacts the vesting of the award (as in the case of a relative total shareholder return (TSR) award)

What Is the Appropriate Accounting for Modifications?

First, as a refresher, “performance conditions” generally include the attainment of specified financial performance targets (e.g., earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) or revenue), operating metrics, or other specified actions under the control of the company (e.g., a liquidity event). Awards with performance conditions are recognized as compensation expense only when it is probable that the performance condition will be satisfied. If the performance condition subsequently becomes improbable, the previously recognized compensation cost is reversed in the period in which the change occurs.

“Market conditions” typically include the achievement of a specified price of the company’s stock or a specified return on/increase in the company’s stock relative to an index or another benchmark. In contrast to performance conditions, awards with market conditions are recognized as compensation expense whether or not they are probable, with the market condition being factored into the fair value of the award.

Accounting for award modifications depends on both (a) the way in which the award is modified, and (b) the type of award that is modified. ASC 718 classifies award modifications into the following four categories, based on the probability that the award will vest immediately pre- and post-modification:

- Type I, or probable to probable

- Type II, or probable to improbable

- Type III, or improbable to probable

- Type IV, or improbable to improbable

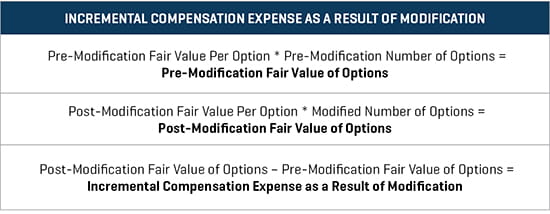

Of these, Types I and III are the most common. Type I modifications typically occur when a company amends an award to reduce the exercise price, extend the exercise period, or adjust the market conditions (e.g., reduce the share price targets). In these cases, the total compensation expense recognized for the award is the sum of the grant-date fair value and any incremental value created by the modification. In order to derive the incremental value created by the modification, the fair value of both the pre- and post-modification options must be measured. As illustrated in Figure 1, the difference in the total fair value between the pre- and post-modification options represents the incremental compensation expense associated with the modification.

Figure 1

Incremental compensation expense is recognized immediately for the portion of the award for which service has already been completed (i.e., the award is vested). Total compensation expense recognized for Type I modifications cannot be less than the original grant-date fair value of the award.

Type III modifications are typically the result of adjustments to performance conditions, such as reductions to EBITDA or revenue targets. When an improbable performance condition is adjusted such that it becomes probable, the total compensation expense recognized for the award is based on the post-modification fair value of the award. As a result, expense is immediately recognized for the portion of the post-modification fair value for which service has already been completed. While expense is not typically recognized for awards with improbable performance conditions, any previously recognized expense would be reversed.

Type II and IV modifications are less common. Generally, the accounting for Type II modifications is in line with Type I modifications, and the accounting for Type IV modifications is in line with Type III modifications. This means that total compensation expense recognized in Type II modifications is equal to the grant-date fair value plus the incremental value created by the modification, while total compensation expense recognized in Type IV modifications is equal to the post-modification fair value (assuming, in both cases, that any performance conditions ultimately become probable).

How Do We Calculate “Incremental Value”?

“Plain-vanilla” employee stock options typically have the following basic economic structure at grant, where the primary variance among companies tends to relate to the length and structure of the time-vesting conditions:

- Exercise price: Set equal to the company’s stock price on the grant date (i.e., “at-the-money”)

- Dividend equivalents: No dividend equivalents paid prior to exercise

- Time-based vesting: A certain percentage of awards vest for each month or year of service (e.g., 20% per year for five years)

- Contractual term: 10 years

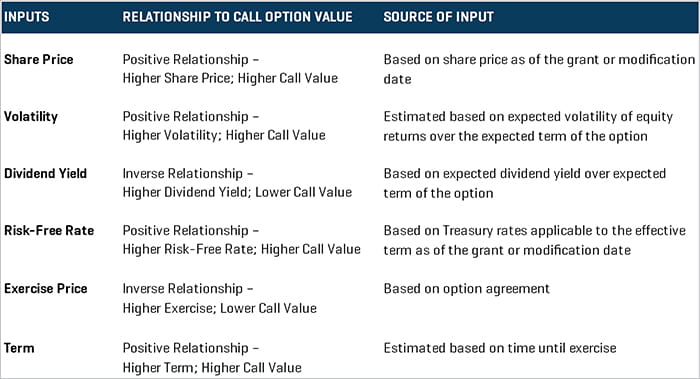

Because of its ease of use and verifiability, the Black-Scholes Option Pricing Model (BSOPM) is generally employed to value plain vanilla employee stock options. A lattice model or Monte Carlo simulation is occasionally required in the case of more complex structures that have market vesting conditions (TSR awards tied to relative peer group performance, options that vest once certain stock price thresholds are achieved, etc.). For the purpose of this example, however, we will focus on a simple BSOPM calculation.

The BSOPM is an arbitrage-pricing model that was developed using the premise that if two assets have identical payoffs, they must have identical prices to prevent arbitrage. The BSOPM relies on six variables: (i) asset price, (ii) strike price, (iii) term, (iv) risk-free rate, (v) volatility, and (vi) dividend yield. Figure 2 presents the directional impact to value of each input to the model as well as typical sources for each input.

Figure 2. BSOPM Inputs and Sensitivities

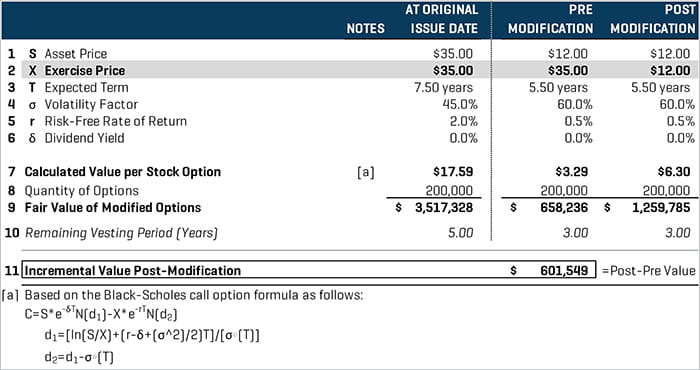

In the following example calculations for a Type I modification, and as depicted in Figure 3, we show the expense impact of a modification to the strike price of an option. We can think about this representative scenario as follows:

- Five-year time vesting (20% per year) plain vanilla stock options were granted with an original, at-the-money strike price of $35.00

- The company’s stock price declined significantly over the next two years, and the board of directors elected to modify the exercise price to at-the-money at the modification date

- Accordingly, we present the initial fair value analysis of the options, as well as the “pre” and “post” modification values, at the time of the modification event

Figure 3. Illustrative Modification Valuation

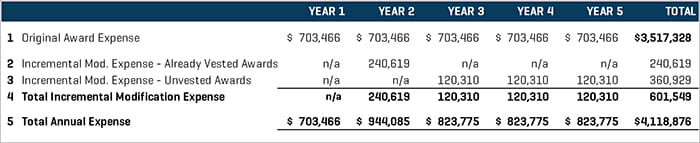

The Figure 3 calculations give us the incremental value resulting from the modification. We next present a representative discussion of income statement expense implications based on the following example, and as shown in Figure 4:

- The original fair value of the awards has been expensed over the first two years ratably

- At the modification date, an additional expense is incurred related to the previously vested awards incremental fair value

- The remaining incremental fair value, in additional to the original fair value, is expensed over the remaining vesting term

Figure 4. Illustrative Modification Expense

Closing Thoughts

Resetting outstanding options may become more prevalent as companies attempt to modify the terms of options to incentivize employees. Because of the earnings impact, it is critical that key assumptions are supported with robust analysis when determining the fair value of pre- and post-modification options.

- Or calculated or intrinsic value, in cases where an alternative measurement method is used.