Fair Value Methods of the Delaware Chancery Court Deciphering the Appraisal Oddities

Subscribe to case alertsFair Value Methods of the Delaware Chancery Court Deciphering the Appraisal Oddities

Subscribe to case alertsIn a review of more than 20 cases since 2010, we examine some of the court’s wide-ranging decisions and how businesses can prepare for such matters.

The U.S. economy is approaching a decade-long recovery that began in 2010 following the Great Recession. Strong economic conditions have been an important factor pushing stock market indices to record highs and driving significant expansion in valuation multiples. The price-to-earnings multiple of companies comprising the S&P 500 index increased from roughly 17.0x in 2010 to nearly 28.0x in 2017 (a 65% increase), while the average enterprise-value-to-EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) multiple paid in acquisitions of U.S. public companies grew from 11.8x in 2010 to 14.5x in 2017 (a 23% increase).[1]

Despite the rise in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) transaction multiples, target company shareholders are not always gracious recipients of the buyout price paid in the deal. These dissenting shareholders instead choose to perfect their appraisal rights and pursue litigation with the hope of receiving not only a higher buyout price, but also accrued interest. Because many U.S. publicly traded companies are incorporated in Delaware, a disproportionate percentage of these cases are tried in the Delaware Court of Chancery (the “court”) under Section 262 of the Delaware General Corporation Law.

Section 262 provides dissenting shareholders of an acquisition target with the right to petition the court for a judicial determination of the fair value of their shares in lieu of receiving the deal price. Because of the shareholders’ decision to dissent, the court has the statutory mandate to “determine the fair value of the shares exclusive of any element of value arising from the accomplishment or expectation of the merger or consolidation … and shall take into account all relevant factors.”[2]

The court has broad discretion in carrying out this mandate. In fact, the court’s decisions commonly state that each case must be decided on its own facts and circumstances, there is no prescribed formula or method for determining fair value, and decisions reached in any particular case might not necessarily apply to other cases. As with any other appraisal, the value conclusion depends substantially on the knowledge, experience, and judgment of the appraiser. Judges in the Delaware Court of Chancery are no exception.

The court’s rulings in recent appraisal cases appear to be wide-ranging and unpredictable, which has attracted the attention of litigators, corporate attorneys, economists, valuation specialists, litigation consultants, and many other constituents. One of the most highly publicized examples involves Dell Inc. In its opinion, In re Appraisal of Dell Inc., the court initially determined the fair value of Dell to be 28% higher than the deal price established through a protracted, thorough, and otherwise well-negotiated sales process. On appeal, however, the Delaware Supreme Court reversed the decision and concluded that the fair value of Dell was, in fact, equal to the deal price. The Delaware Supreme Court aptly stated in its decision, “Appraisals are odd.”[3]

Appraisal Case Review

In order to better understand some of these Delaware appraisal oddities, we reviewed 23 cases involving acquisitions of U.S.-listed companies decided since 2010, and then classified the cases through a two-step process. The first step considered two questions:

- Was the buyer financial or strategic?

- Did the court deem the sale process to be robust or compromised?

The first question is unambiguous, but the second question requires interpretation. The terms “robust” and “compromised” are difficult to define with precise conditions. A robust sale process is generally thorough, honest, fair, and effective in achieving its intended purpose. In terms of specific evidence noted in the court’s decisions, a sale process is considered to be robust if it has several of the following attributes:

- Incorporated a comprehensive and unimpeded search of potential interested buyers

- Conducted over a sufficient duration to allow interested parties to perform adequate due diligence and engage in arm’s-length negotiations

- Provided qualified buyers with financial data and other information that was accurate and complete

- Reflected a fair and level playing field of information, with no buyer having an inappropriate advantage

- Lacked any evidence of self-interest, self-dealing, or preferential treatment afforded to any buyer (including insiders)

- Contained go-shop (or market-check) provisions in the merger agreement that were free of terms and conditions that could materially obstruct or restrict the sale process

This list is not exhaustive. These items and conceivably other issues are considered by the court as an overall body of evidence in concluding whether a sale process is robust or, alternatively, “compromised” in some way, shape, or form. In our sample of cases, the court considered 14 to be robust and nine to be compromised.

The second step of our review process categorized the court’s decisions regarding the fair value of the dissenters’ shares according to four alternatives:

- Deal Price: the price paid to the company’s shareholders in the transaction.

- Deal Price Less Synergies: an amount that removes from the Deal Price any “element of value arising from the accomplishment or expectation of the merger or consolidation,” which are generically referred to herein as “synergies”

- Unaffected Stock Price: the company’s actual trading price measured over a time period considered to be not impacted by the transaction

- Appraised Value: an estimated share price determined by the court based on valuation methods and assumptions the judge believes to be reasonable and appropriate based on the evidence

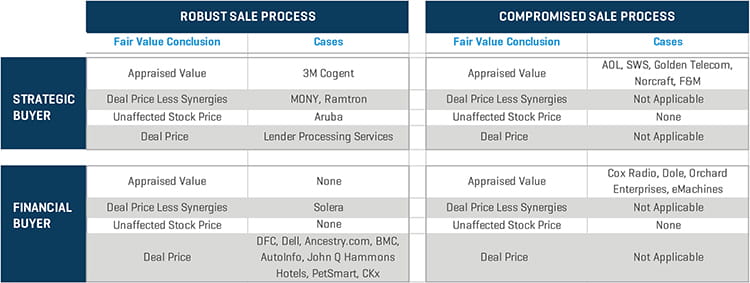

We summarize our results in Figure 1 and offer several observations thereafter.

Figure 1: Statutory Fair Value Matrix

Compromised Sale Process

Starting with the right-hand side of the matrix, if the transaction was consummated through a compromised sale process, the court has consistently relied on the Appraised Value for the dissenters’ shares. Whether the buyer was financial or strategic had no impact on this decision. The only other viable valuation method available to the court, at least in our view, is the Unaffected Stock Price. Relying on the Deal Price or Deal Price Less Synergies on this side of the matrix would be contradictory because the sale process that produced the Deal Price is considered to be compromised. While the court considered the Unaffected Stock Price as a potential indicator of the fair value for Norcraft Companies, Inc., it was ultimately dismissed due to the company’s limited public trading history, relatively low trading volume, and sparse analyst coverage.[4]

Curiosity would generally compel a comparison of the Appraised Value with the Deal Price for these nine cases, but doing so is essentially procedural and yields little utility on this side of the matrix. As noted earlier, the Deal Price is generally not considered to be a reliable fair value indication on its own merits.

Robust Sale Process

Unlike its counterpart, the left-hand side of the matrix shows that the court’s fair value conclusion is critically impacted by whether the buyer is financial or strategic.

Financial Buyers: If the transaction was achieved by a financial buyer through a robust sale process, the court has consistently relied on the Deal Price for the fair value of the dissenters’ shares. While this finding might seem intuitive and unsurprising, it is noteworthy that all of the cases in this quadrant of the matrix included substantial analysis and testimony by each party’s retained expert attempting to persuade the court that the final fair value conclusion should be based on a different method than the Deal Price. Of course, the court was not persuaded.

The single exception in this quadrant of the matrix is the case involving the acquisition of Solera, in which the Court relied on the Deal Price Less Synergies for its fair value conclusion. While most financial buyers acting alone generally lack the means to achieve revenue, cost, and operational benefits commonly associated with the term “synergies,” the court noted in the case of Solera that other portfolio companies of Vista Equity Partners (the buyer) provided such synergistic opportunities. The court noted that Vista and its expert considered “private company cost savings and the tax benefits of incremental leverage” in its Deal Price Less Synergies analysis.[5] The court found the synergies analysis convincing and concluded that the fair value of the dissenters’ shares was 3.4% below the Deal Price.

Strategic Buyers: Turning to the strategic buyer quadrant of the matrix, the court’s decisions have shown much greater divergence in the method relied on to determine the fair value of the dissenters’ shares. Of the five cases in this quadrant, two decisions relied on the Deal Price Less Synergies while the other three cases are scattered across the other valuation methods.

Here is a summary of the court’s findings related to synergies for the two cases that relied on the Deal Price Less Synergies for the fair value conclusion.

Ramtron International Corporation: The company’s expert determined a synergy value based on expected cost savings following the transaction. The petitioner’s expert, however, successfully argued that synergy value should also consider “negative revenue synergies and transaction costs.” The court’s decision did not elaborate on either of these items. We speculate that negative revenue synergies might reflect cannibalization of product sales, which is commonly observed when two competitors are combined. In the case of transaction costs, however, it is unclear whether they were related to the transaction itself (i.e., fees for attorneys, bankers, consultants, and other advisors) or represented integration or other one-time costs expected to be incurred following the deal. Nonetheless, the Ramtron case shows that the court considered “net” synergy value in reaching its fair value conclusion.

The MONY Group, Inc.: The court’s determination of fair value gave consideration to the Deal Price Less Synergies (75% weight) and a sum-of-the-parts valuation of the company (25% weight). While the court noted that “neither party fully satisfied its burden of persuasion regarding a valuation of MONY,” the sum-of-the-parts valuation of MONY performed by the company’s expert (which included actuarial appraisal analyses) was more credible. With respect to synergies, only the company’s expert presented an analysis supporting his determination of value, which the court relied on after making certain adjustments.

We now turn to the court’s decisions for the other three cases in this quadrant of the matrix. Setting aside Solera as a somewhat unique case for a financial buyer transaction, the rationale for the court’s decisions in these strategic buyer deals is perplexing because one would generally expect the following logic to apply:

-

Strategic buyers are generally able to pay higher prices than financial buyers because of their ability to achieve revenue, cost, and operational synergies that are not available to financial buyers.

Strategic Buyer Purchase Price = Financial Buyer Purchase Price + Synergy Value

-

Removing synergy value from a strategic buyer purchase price should approximate the financial buyer purchase price.

Strategic Buyer Purchase Price - Synergy Value = Financial Buyer Purchase Price

-

Because the court, as shown in our matrix, has consistently found that the financial buyer purchase price reflects fair value, it should follow that the strategic buyer purchase price minus synergy value (as shown in the formula immediately above) also reflects fair value. In other words, the Deal Price Less Synergies in a strategic buyer transaction should reflect the fair value for the dissenters’ shares.

Fair Value = Strategic Buyer Purchase Price - Synergy Value

Considering the foregoing, why did the court not rely on the Deal Price Less Synergies to value the dissenters’ shares in the other three cases shown in this quadrant of the matrix? In short, the court attempted to do exactly that, but was unsuccessful for very specific reasons.

3M Cogent, Inc.: Neither the petitioner’s expert nor the company’s expert presented any explicit analysis of synergy value. The only mention of synergy value occurred when the company’s expert “applied a 20% discount to the [comparable transaction] multiples they obtained to take into account the need to eliminate any control or synergy premiums.” While the court agreed conceptually with the company’s expert, noting that “some discount would be appropriate,” the court ultimately dismissed both experts’ comparable transaction analyses.

Comments made by the court appear to suggest that the company’s conflicting comments on fair value, rather than any shortcomings in the sale process, ultimately compelled the judge to dismiss the deal price as evidence of fair value and instead perform its own appraisal of the dissenters’ shares. The court noted further that the “Respondent and its experts also did not attempt to adjust the merger price to remove the speculative elements of value that may arise from the ‘accomplishment or expectation’ of the merger,” and that “those deficiencies render the merger price largely irrelevant to this case.” Because the merger price was deemed irrelevant by the court, it could no longer rely on the Deal Price Less Synergies as the fair value of the dissenters’ shares. Thus, the court defaulted to Appraised Value.

Aruba Networks, Inc.: The opposing experts each relied on discounted cash flow (DCF) analyses to determine the fair value of the dissenters’ shares but with divergent conclusions commonly observed in appraisal cases. The court ultimately dismissed each expert’s DCF analysis, for lack of “reliability” in the case of the petitioner’s expert and lack of “methodological rigor” in the case of the company’s expert. In contrast to other Delaware appraisal cases, the court did not perform its own DCF analysis for Aruba. Rather, the court stated that the “two probative indications of value in this case are the unaffected market price of $17.13 and the deal-price-less-synergies value of approximately $18.20 per share.”

The court noted that “the transaction in this case generated substantial synergies,” but neither expert presented any explicit analysis of synergy value. The court ultimately relied on a synergy value estimated by McKinsey & Company on behalf of Hewlett-Packard Company (the buyer) as the starting point in its analysis of the Deal Price Less Synergies. The court allocated the total synergy value between Aruba and Hewlett-Packard shareholders using a March 2013 study by the Boston Consulting Group.

While the Unaffected Stock Price and Deal Price Less Synergies were reasonably similar, the court stated that, “for Aruba, using its unaffected market price provides the more straightforward and reliable method for estimating the value of the entity as a going concern.” In support of that determination, the court noted that the Deal Price Less Synergies figure “could have errors at multiple levels” and otherwise still incorporate “an element of value resulting from the merger.” These trepidations ultimately compelled the court to abandon the Deal Price Less Synergies and instead rely on the Unaffected Stock Price in its determination of fair value.

Lender Processing Services, Inc.: The acquisition of Lender Processing Services, Inc. (LPI) by Fidelity National Financial, Inc. was noted as a strategic combination that included consideration paid to LPI shareholders in equal amounts of cash and Fidelity common stock. The opposing experts each relied on DCF analyses to determine the fair value of the dissenters’ shares, again with substantially different conclusions. The court dismissed the experts’ DCF analyses and instead performed its own DCF analysis, achieving a value that was 4% higher than the Deal Price.

In reaching its final determination of fair value, the court noted that the LPI case “is most similar to AutoInfo and BMC,”[6] noting that these cases relied on the Deal Price as the fair value conclusion. Curiously, AutoInfo and BMC were acquisitions completed by financial buyers rather than strategic buyers, which, based on prior court decisions, would make them different from LPI in terms of whether to rely on the Deal Price as the best evidence of fair value.

The court further noted that “[its] DCF analysis depends heavily on assumptions,” and therefore gave “100% weight to the transaction price.” Moreover, since the court’s DCF value was 4% higher than the price negotiated in a robust sales process involving a strategic buyer, we speculate this directional difference contributed to the court’s concerns about the assumptions underlying its DCF analysis.

The most noteworthy aspect of the LPI case occurred just before the court reached its final decision. The company argued that the court should adjust the Deal Price for some portion of the synergies expected to arise from transaction. While the court noted “that is a viable method,” neither expert performed any explicit analysis of synergies. Moreover, the company’s expert affirmed at trial that he “did not have any basis to opine regarding a specific quantum of synergies.” The court stated that “having taken these positions, it was too late for the company to argue in its post-trial briefs that the court should deduct synergies."

Gaining Clarity

While the court’s rulings in recent Delaware appraisal cases appear to be wide-ranging and unpredictable, reviewing the decisions in light of the sale process (robust or compromised) and buyer profile (financial or strategic) reveals that the court has, in fact, been highly consistent in the valuation method relied on for their fair value determinations. This is particularly true at least with respect to the intention of the court.

Parties in appraisal proceedings would be well-served to perform sufficient analysis around the sale process to gauge their level of confidence regarding the court’s determination of whether it was robust or compromised. The analysis would include a review of the sale process attributes noted earlier as well as other factors that are relevant to the case.

When a sale process is deemed to be robust, the court generally intends to place a high degree of reliance on the Deal Price in financial buyer transactions and the Deal Price Less Synergies in strategic buyer transactions, so long as the facts and circumstances of each case allow for such reliance. When a sale process is compromised in some way, the court consistently relies on the Appraised Value of the dissenters’ shares regardless of the buyer profile.

Some of the unpredictability in the court’s rulings, at least with respect to transactions completed by a strategic buyer through a robust sale process, appears to be due to the absence of comprehensive and convincing valuation analysis and testimony. Not only should the experts perform DCF analyses (one of the generally preferred valuation methods of the court when an appraisal is required), but they should also prepare analyses of the synergies expected from the transaction. While the court might not rely explicitly on the synergy analysis in reaching its final decision, the inclusion of such analysis can provide the court with important evidence as it considers “all relevant factors.”

The logical follow-up question is: What analyses should be prepared for the synergy value and its allocation between buyer and seller?

The answer to this question is the subject of the second article of this series.

- Source: S&P Capital IQ. Includes acquisitions of U.S. publicly traded companies in which the percent sought was greater than 50%. EBITDA refers to earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization.

- 8 Del. C. 1953, § 261 (h)

- Dell Inc. v. Magnetar Glob. Event Driven Master Fund Ltd. – A.3d – 2017 WL 6375829 (Del. Dec. 14, 2017).

- Norcraft Companies, Inc. v. Blueblade Capital Opportunities LLC C.A. No. 11184-VCS (Del. July 27, 2018).

- In re Appraisal of Solera Holdings, Inc. Memorandum Opinion C.A. No. 12080-CB (Del. July 30, 2018).

- Merlin P’rs LP v. AutoInfo, Inc., 2015 WL 2069417, at *11 (Del. Ch. Apr. 30, 2015) and Merion Capital LP v. BMC Software, Inc., 2015 WL 6164771, at *11 (Del. Ch. Oct. 21, 2015).

Sujets Liés

-

Examen Judiciaire

Fair Value Methods of Delaware Chancery: Deal Price Less Synergies

-

Examen Judiciaire

Dans l’affaire Norcraft, le tribunal du Delaware offre des indications supplémentaires en matière d’évaluation.

-

Examen Judiciaire

Tendances des taux de croissance à long terme dans les décisions du Delaware Court of Chancery