GAAP and IFRS Convergence in Value, Divergence in Application

GAAP and IFRS Convergence in Value, Divergence in Application

While global financial reporting standards have become more uniform, we examine the differences in common applications of fair value measurements.

While the definition of fair value is converged between generally accepted accounting principles used in the United States (U.S. GAAP) and international financial reporting standards (IFRS) promulgated by the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB), the application of certain fair value measurements remains somewhat diverged.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has not indicated support for U.S. reporting entities to prepare financial statements in accordance with IFRS. However, most major capital markets outside of the U.S. have either adopted or indicated that they intend to adopt IFRS. In modern capital markets, where companies have multiple options to list globally, it is important for companies and investors to understand the differences that exist to apply and interpret financial information. Instances where U.S.-based preparers of financial statements may need to consider IFRS include:

- M&A opportunities in international markets

- Raising capital in international markets

- Statutory reporting requirements of non-U.S. subsidiaries

- First-time adoption of IFRS (IFRS 1)

Under the Norwalk Agreement of 2002, the Financial Accounting Standards Board and International Accounting Standards Board formally indicated their commitment to convergence of U.S. GAAP and IFRS. In many ways, there has been significant progress; still, meaningful differences remain. Herein, we in no way intend to provide an exhaustive list of differences between U.S. GAAP and IFRS, but instead aim to make readers aware of differences in the most common applications of fair value-based financial reporting measurements.

Business Combinations (Accounting Standards Codification Topic (ASC) 805/IFRS 3)

Business combinations are accounted for under the acquisition method whereby an acquirer obtains control of one or more businesses. Frequently encountered differences between the two reporting regimes include the following.

Value Attributed to Noncontrolling Interests (NCI)

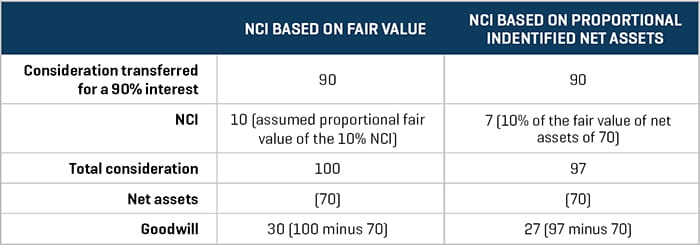

Under ASC 805, the acquirer is required to record any noncontrolling interest at fair value. The corresponding impact on the so-called left-hand side of the balance sheet is a proportionate increase to the value of the assets acquired (i.e., goodwill). Under IFRS 3, NCI ownership interests that entitle the holder to a proportionate share of net assets in a liquidation may be measured at either a) fair value including goodwill or b) the NCI’s proportionate share of the acquiree’s aggregate identifiable net assets excluding goodwill. As a result, all other things being equal, the amount of NCI and goodwill booked may be lower under IFRS if the buyer selects the latter option, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Definition of Control

For a business combination to occur, an acquirer must obtain control over the acquired business. U.S. GAAP and IFRS define control differently, and as a result, the same transaction may be accounted for as a business combination under U.S. GAAP but not under IFRS, or vice versa. Generally speaking, U.S. GAAP defines control as “the ownership of a majority voting interest, and therefore, as a general rule, ownership by one reporting entity, directly or indirectly, of more than 50% of the outstanding voting shares of another entity is a condition pointing toward consolidation.

Under IFRS, “an investor controls an investee when the investor is exposed, or has rights, to variable returns from its involvement with the investee and has the ability to affect those returns through its power over the investee.”

Given the somewhat broader definition of control under IFRS, a transaction that qualifies as a change-of-control transaction under IFRS may not qualify as such under U.S. GAAP.

Related to the above, the definition of a business also varies between U.S. GAAP and IFRS. While these are nuanced and beyond the scope of this article, it is important to know that differences in the definition of a business exist that would impact financial reporting for business combinations.

Assignment/Allocation of Goodwill

Under U.S. GAAP, goodwill is assigned to an entity’s reporting units, defined as the same as, or one level below, an operating segment. The determination of reporting units is based on a company’s segment reporting structure. Under IFRS, goodwill is allocated to cash-generating units (CGU). A CGU is the smallest identifiable group of assets that generates cash inflows largely independently of other assets or groups of assets. Thus, the IFRS model may result in more CGUs versus reporting units under U.S. GAAP.

Contingent Consideration and Related Subsequent Measurement

Under both U.S. GAAP and IFRS, contingent consideration associated with a transaction is initially recognized at fair value. In relation to subsequent measurement, reporters preparing financial statements under U.S. GAAP would remeasure the contingent consideration asset or liability to fair value at each reporting date. IFRS preparers need to first determine if the contingent consideration asset or liability qualifies as a financial instrument. If it does, the treatment is consistent with U.S. GAAP. If it does not, it should be accounted for under another applicable IFRS framework. Note that contingent consideration classified as equity is not remeasured under either U.S. GAAP or IFRS.

Goodwill Impairment Testing (ASC 350/International Accounting Standard (IAS) Topic 36)

Recent changes to U.S. GAAP have bridged certain significant differences with IFRS, such as the shift to a direct calculation of goodwill impairment under ASC 350 resulting from Accounting Standards Update (ASU) 2017-04, which more closely aligns with IFRS. Still, the impairment framework applied under IAS 36 is significantly more prescriptive than the fair value-based model promulgated by ASC 350.

Under U.S. GAAP, the carrying value of a reporting unit is tested against its fair value to identify an indication of impairment and then ultimately to quantify an impairment charge. Under IFRS, the carrying value of the CGU is compared with its recoverable amount, which is defined as the greater of its a) value in use (VIU) and b) fair value less cost to sell (FVLCTS). In our experience, for a going-concern that will continue to operate, the entity’s VIU typically exceeds its FVLCTS. The following highlights certain differences between the fair value measurement approach under U.S. GAAP and the VIU approach under IFRS.

Market Participant vs. Entity-Specific Cash Flows

Under ASC 350, cash flows used in a fair value measurement are defined as that which a market participant could reasonably expect to realize from the asset, which may differ from that available to the current owner. Under the IFRS VIU framework, the cash flows represent what the reporting entity expects to realize from its investment in the asset (i.e., they reflect entity-specific assumptions).

Fair Value vs. Value in Use

In order to calculate the fair value of an asset, generally accepted valuation approaches and methods must be considered, and the value determination must be derived by applying the most applicable method(s). VIU is far more prescriptive and requires the preparer to apply a cash flow model that considers a maximum five-year discrete period, unless a longer period can be supported (which is usually the case with finite-lived or early stage assets), on a pre-tax basis (discussed further below).

Carrying Value – Deferred Tax Considerations

Impairment testing under IFRS is typically performed on a pre-tax basis, and as such, deferred tax assets and liabilities are excluded from the carrying value calculations. Consistently, the cash flow projections are not affected by specific tax attributes, such as net operating loss carryforwards. Under U.S. GAAP, deferred tax assets and liabilities are included in the carrying value calculations, and as such, the cash flow implications of entity- or transaction-specific tax attributes are reflected in the calculation of future tax payments.

Practical Pre-Tax Valuation Issues

Fair value is typically measured on a post-tax basis. Under IAS 36, reporting entities are required to perform and present certain metrics associated with an impairment test on a pre-tax basis. Theoretically, this is to be consistent with the tax agnostic framework discussed above. Practically, and as acknowledged in the IASB's Basis for Conclusions to IAS 36, valuation metrics (such as discount rates) are quantified using post-tax/real-world data. Therefore, it is generally accepted that the VIU test is performed on a post-tax basis (excluding entity-specific tax attributes) and that certain metrics that need to be disclosed (such as the pre-tax discount rate) are imputed by removing tax cash flows and solving for the pre-tax discount rate that arrives at an equivalent value to the post-tax analysis.

Impairment Testing for Other Long-Lived Assets (ASC 360/IAS 36)

Two key differences that we often encounter in relation to impairment testing of long-lived (other than indefinite-lived) assets relate to the testing framework and future treatment of prior impairment losses.

Impairment Testing Framework

U.S. GAAP requires that, for long-lived asset groups (other than indefinite-lived assets), the preparer perform a two-step approach whereby one first tests whether the sum of the undiscounted cash flows exceed the carrying value of the asset group. If the asset fails this test, the fair value (discounted) of the asset group is compared to the carrying value in order to quantify the impairment charge. Under IFRS, the recoverable amount (higher of VIU and FVLCTS) is compared to its carrying amount, and any impairment charge is equal to the difference. Accordingly, there may be situations where an asset would be deemed impaired under IFRS but not under U.S. GAAP.

Future Treatment of Impairment Losses

With the specific exception of goodwill, IFRS preparers may be able to reverse historical impairment losses if the value recovers in subsequent periods. Under U.S. GAAP, the reversal of prior impairment losses is strictly prohibited.

Stock/Share-Based Compensation (ASC 718/IFRS 2)

While ASC 718 addresses stock-based compensation exclusively, IFRS 2 Share-Based Payments addresses equity-based payments to both employees and other vendors. While there are many ways in which ASC 718 and IFRS 2 have converged, there are many small but potentially impactful differences that preparers should consider.

Simplified Method

Under SAB 14, released by the SEC, U.S. preparers may apply a simplified method to estimate the expected holding period and valuation term for granted options. Under IFRS, no similar guidance is available, so preparers typically quantitatively support the expected exercise period based on historical tenure rates and other internal and market data. The option holding period under IFRS will typically require more support than under U.S. GAAP, where the simplified method may be used.

Vesting Patterns for Graded Options

Under U.S. GAAP, preparers generally have the option to select the vesting pattern of graded options: a) on a straight-line basis, or b) based on the vesting term of each tranche (effectively accelerating vesting based on the respective vesting period of each tranche). Under IFRS 2, preparers are required to treat each tranche as a separate grant and vest accordingly, effectively accelerating vesting based on the respective vesting period of each tranche. U.S. GAAP preparers have an option to slow the recognition of stock compensation expense that IFRS preparers do not.

Despite their best efforts, full convergence appears unlikely in the near term. Therefore, it is important for preparers and investors to understand the differences between the two frameworks.