Economic Headwinds: How Can Hedging Help?

Economic Headwinds: How Can Hedging Help?

Recently, the failures of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank put banks under the scanner, especially small and midsized regional banks. Markets are strife with speculations, and a question keeps popping up: How could we have avoided these failures?

On May 1, the First Republic Bank (FRB) became the second-largest bank failure in U.S. history. The bank suffered from a run on deposits just weeks after the collapse of SVB and Signature Bank. A lot of banks like PacWest and Western Alliance are reeling under pressure. Pundits attribute many factors to the bank failures, such as depositor concentration, low fixed-rate held-to-maturity (HTM) / available-for-sale (AFS) mortgage-backed securities (MBSs) and U.S. treasuries, low allowance for credit loss (ACL) and net charge-offs, sector concentration, deposit outflows, and ineffective asset-liability management (ALM) / hedging strategies.

This article discusses fixed-rate assets, their impact on the existing banking crisis, the use of hedging instruments, and the extent of their use by banks to protect themselves from the impact of rising rates.

Fixed-Rate Assets

Banks typically cannot operate without a significant part of their balance sheet tied in fixed rate assets, either fixed-rate loans or fixed-rate securities. Banks would like a predictable income stream. The predictability is essential, as it provides coverage for liabilities by providing a stable source of cash flows and provides a path to profitability.

That said, investing in fixed-rate assets, despite its advantages, is prone to certain risks, especially in an inflationary environment. For example, consider a bank that funds long-term assets via short-term liabilities that generally have floating interest rates. As the rates go up and short-term liabilities mature, the new liabilities would attract higher interest, while the assets may still fetch the same fixed rate. The mismatch in interest rates for assets and liabilities may put pressure on the bank’s margin. Further, as the rates go up, the value of fixed-rate assets declines. This may reduce the bank’s ability to sell the assets without incurring significant losses. SVB is a prime example of this situation, as it had to sell its available-for-sale (AFS) portfolio at a loss of $2 billion to meet its liquidity needs.

Depending on the accounting classification of these assets (i.e., HTM or AFS), the decline in the value of those assets may bring a negative impact on banks’ equity. For example, any change in the fair value of AFS securities does not impact the income statement but is captured in accumulated other comprehensive income (AOCI).

The AOCI is a component of equity and negatively impacts the bank’s capital for unrealized losses resulting from a decline in the fair value (FV) of AFS assets. Any FV losses on the HTM securities do not impact the capital until sold. However, this advantage is a double-edged sword; although unrealized losses do not impact the capital, the losses continue to build due to rising rates. If these securities are required to be sold to meet liquidity requirements, for example, such accumulated losses may wipe out a substantial portion of the bank’s equity.

In its 2022 10-K, the Bank of Hawaii stated that it had $985 million of unrealized losses on loans and $799 million of unrealized losses on HTM securities. The combined $1.8 billion exceeded the Bank of Hawaii’s $1.3 billion of total equity. Many other banks are in a similar situation, which can have a huge impact on their equity if they are required to sell these assets and realize accumulated losses.

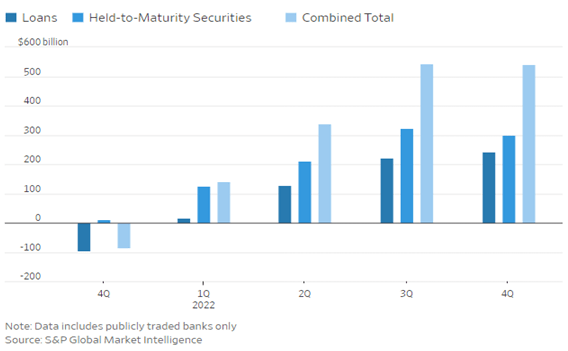

Among 435 publicly traded U.S. banks listed on major exchanges, 97% of them reported that their loans’ market value was less than their balance-sheet amount as of December 31, 2022, according to data provided by S&P Global Market Intelligence. Combined, they had $242 billion of unrealized losses on their loans, defined as the difference between the loans’ fair values and carrying amounts. That was equivalent to 14% of their total equity and 21% of their tangible common equity, which is a widely used measure of net worth that excludes preferred stock and intangible assets. A year earlier, the same banks said their loans’ fair value exceeded their carrying amount by $96 billion, the data shows. The same group showed $299 billion of unrealized losses on HTM as of December 31, 2022. Those losses aren’t included on companies’ balance sheets.1

Marketing to Market: Fair-value losses on banks’ loans and securities grew as interest rates rose2

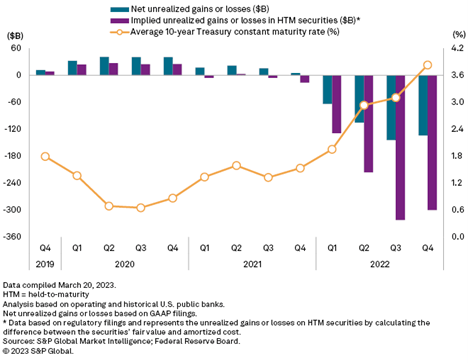

S&P Global Market Intelligence shows how the tides have turned from 2021 to 2022. Public banks that had reported unrealized gains on their AFS securities portfolio were showing unrealized losses in 2022. The Fed raised rates seven times in 2022, and as the rates went up, the value of these securities declined while unrealized losses accumulated. Both HTM and AFS portfolios are getting hammered and are accumulating huge losses. As HTM losses are not captured in the financial statements and do not impact the capital or equity of the bank, some large banks have transferred large portion of their securities from AFS to HTM.3 This transfer would not impact the losses that have already been captured in AOCI but will help banks avoid future losses.

Net unrealized gains or losses at U.S. public banks4

Interest Rate Contracts

According to Call Report data for December 31, 2022, banks with over $10 billion in assets had 22.3% of total assets invested in interest rate swaps (IRS), while only 3.2% of the total assets were invested by banks between $3 billion and $10 billion in total assets. Banks below $3 billion in total assets did not have any IRSs. The percentage of these swaps is considerably less for hedging purposes, as most interest-rate derivatives were used for trading purposes. The Bank of Hawaii, which had its entire equity overtaken by unrealized losses, did not have any hedges in place to protect its interest rate risk (IRR). SVB, which had $15 billion of fair value hedge (FVH) at the end of 2021, had only $500 million of FVH at the end of 2022.

Hedging Risks

Rebalancing a liability sensitive portfolio into an asset sensitive one in the rising rate environment may not be an easy endeavor, especially when there are accumulated unrealized losses. One may not be able to do so without realizing significant losses.

That said, hedging may enable mitigating the impact of a decline in fair values of fixed-rate assets. According to a research article, only about 6% of bank assets across the banking sector were protected by IRSs, which are typically used by banks to protect declining values due to rising rates. Even as rates continued to climb throughout 2022, about a quarter of publicly traded banks reduced their protective hedging last year. For instance, SVB hedged about 12% of its securities portfolio at the end of 2021 but only 0.4% by the end of 2022.5

Fair Value Hedge

A fair value hedge (FVH) is an approach a bank can take to manage fair value risk. The objective of an FVH is to reduce potential volatility in financial statements caused by changes in the FV of a specific asset or liability. However, only a few large banks rely on this hedging technique. Complex accounting rules and a lack of experience in capital markets may lead many banks to shy away from hedging their interest rate risk. That said, the accounting rules have relaxed some of the accounting complications and introduced new guidelines, such as the portfolio layer approach to hedge the IRR on prepayable securities, which was deemed almost impossible to hedge a few years ago.

The mechanics of an FVH are simple. The risk in the loss of value of AFS security attributable to interest rate is isolated and recognized in the income statement, and it is then offset by an increase in the value of interest rate derivative (IRD), leaving zero to minimal noise on the income statement. The fair value changes attributable to other factors (e.g., credit and market spreads) are recognized in OCI – this FV change is minimal and thus will not have significant consequences for the bank’s equity. Note that HTM securities are not allowed to be fair value hedged, as their fair value does not pose any earnings exposure for a bank.

The banks that are heavily invested in fixed-rate assets should take effective measures to check the menacing impact of rising rates. While hedging may seem daunting in the beginning, the benefit it provides outweighs the pain of learning to apply it. An effective hedging strategy could be the difference between weathering the storm or getting lost in it.

This article was originally published in the Ohio Bankers League’s “BankServices” newsletter.

- “Declines in Loan Values Are Widespread Among Banks,” Jonathan Weil, The Wall Street Journal, April 7, 2023.

- “Declines in Loan Values Are Widespread,” Jonathan Weil.

- “US banks’ liquidity crunch put underwater bond portfolios in focus,” Ronamil Portes, Nathan Stovall, S&P Global Market Intelligence, April 5, 2023.

- “US banks’ liquidity crunch,” Ronamil Portes, Nathan Stovall.

- “Limited Hedging and Gambling for Resurrection by U.S. Banks During the 2022 Monetary Tightening?” Erica Xuewei Jiang, Gregor Matvos, Tomasz Piskorski, Amit Seru, Social Science Resource Network, April 18, 2023.