Strategic Alternatives: Insights on Ownership Transitions

Strategic Alternatives: Insights on Ownership Transitions

Balancing the company’s valuation, business continuity, and other considerations as ownership shifts

In a conversation presented at the 2021 MAPP (Manufacturers Association for Plastics Processors) Benchmarking and Best Practices Conference, Michael Benson, Managing Director in Stout’s Investment Banking group, spoke on the range of strategic alternatives, timelines, and important pros and cons to consider when a business ownership transition is imminent.

He was joined by two distinguished plastics business owners: Kelly Goodsel, President and CEO of Viking Plastics, and Jay Bender, CEO and Owner of Falcon Plastics.

One of the key decisions a business owner will face is when and how to address a major ownership transition. Owners facing this decision may find that their interests begin to diverge from the interests of the company, and they will need to weigh the importance of maximizing the valuation of the business against other considerations such as business continuity or a rushed timeline.

Benson, Goodsel, and Bender presented a variety of strategic alternatives to consider when striving to satisfy all relevant stakeholders related to the deal.

Examining Strategic Alternatives for an Ownership Transition

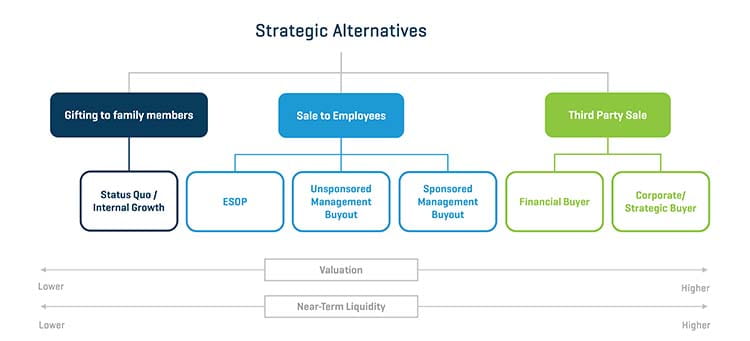

As shown in Figure 1, strategic alternatives include an ESOP transaction, unsponsored and sponsored management buyouts, and sales to private equity or strategic buyers. Each alternative offers advantages and drawbacks.

ESOP Transaction

In an ESOP (employee stock ownership plan) transaction, an ESOP trust is formed and borrows debt to purchase shares over time from shareholders. Because a company can only handle so much leverage, this is usually done in three stages of four- to five-year tranches. A third of the business is bought, and once the debt is paid off (likely in four to five years), the next third is purchased, and so on.

Benson said that this allows ownership of the business to be transferred to employees over time. An ESOP trust is also tax exempt.

“You’re able to reward the employees, and this essentially goes into the retirement account,” he said. “So a lot of groups see that as a pretty big advantage.”

However, this leads to limited liquidity at the sale since ownership is typically only going to get a third of the business value at closing. Plus, the debt used to acquire the company could have been used for growth.

“It’s probably not going to maximize value,” he said. “Valuation is always very tricky in ESOPs because they’ve got to be very careful to obviously not overvalue the business as it is being sold to the employees.”

FIGURE 1: Strategic Alternatives

Unsponsored Management Buyout

In an unsponsored management buyout, ownership of the business is transferred to the management team without any outside equity. The purchase is usually undertaken through a combination of management equity, third-party financing, and a seller note.

Benson explained that this approach allows business continuity, as there is very little disruption to business operations. However, the seller is not getting much liquidity at the point of sale and retains a significant amount of risk exposure.

“The seller is still going to have risk in the business because they have that seller note that they’re being paid back over time,” he said. “It might even be a situation where the bank may not even allow you to make payments to the seller for the first couple years until that bank debt gets paid down.”

Sponsored Management Buyout

A sponsored management buyout occurs when private equity purchases ownership in the company. Management is still able to retain ownership but only as much as they are able to contribute in equity. Many times, private equity will offer equity incentive plans, allowing management to earn additional equity over time.

Benson said that a sponsored management buyout allows a higher near-term valuation and the potential for complete liquidity, depending on the percentage the private equity firm and management team can acquire.

“The disadvantages are that, depending on the situation — and this is with private equity coming in and if the selling shareholder is very important to the business — they’re going to need a longer transition period. So they’re going to need at least 12 months, maybe even 24 months, to transition out of that business.”

Sale to Private Equity

Goodsel spoke about the importance of alignment with a private equity buyer, which can determine the success of an ownership transition. In any buyout, there will be complications if management is not aligned with the new ownership.

Advantages of a sale to private equity include the potential for partial or complete liquidity and the ability for the owner to maintain an ownership stake. Shareholders can pursue future goals with the help of a capital partner. However, the transition can take at least 12-18 months, and there is the possibility of significant operational changes being made to the company.

“Everybody gets so excited about the sale process,” he said. “If you get into the heat of the moment of ‘I can sell my business for $10 million,’ and all you get focused on is that number, you start to lose alignment of what you’re really trying to do for the company and the company objectives. So spending a lot of time during the due diligence process to understand who the potential buyers are, whether it’s private equity or a strategic buyer, is really, really important for sellers and for the management team so that there is alignment.”

Sale to Strategic Buyer

A sale to a strategic buyer is the most straightforward, as the buyer acquires the company outright. This leads to a high near-term valuation, the potential for complete liquidity, and little to no risk to shareholders while offering a very short transition period. However, owners receive no exposure to any future upside in the company.

Goodsel explained that since these are often sales to competitors (though not always), there is high potential for significant changes being made to the company following the transaction.

“You are turning your house over to someone else, and they can do anything they want with the house,” he offered as an example. “People have to recognize that and really be in alignment with the strategic buyer’s intent.”

Owners may fear sales to strategic buyers, especially competitors, since it introduces the possibility of current management being removed or significantly restructured. This is possible, revealing the need for alignment with the buyer, but a removal of previous management is not guaranteed.

“Both private equity and strategic buyers are looking for good, talented people. If you have a management team that is knocking the cover off the ball, leading with strategic intent, maintaining a strong culture, and taking on risk and thinking creatively, the buyer of that business is going to want that management team to remain,” he said.

Corporate and Shareholder Objectives

Benson detailed the need for business owners to recognize corporate objectives and shareholder objectives as distinct from one another.

Corporate objectives consist of what the management team and employees of the business want: A competitive position through acquisitions and/or internal growth, access to capital, financial flexibility, and maximized shareholder value.

Shareholder objectives, overlapping but distinct from corporate objectives, tend to consist of minimized dilution, an acceptable risk/return profile, liquidity, and a maximized shareholder value.

The potential conflicts of these two may become evident as ownership ages. At the genesis of a company, a younger business owner typically has an appetite for growth and a higher tolerance for risk taking. Liquidity is less important, the company has a seemingly infinite time horizon, and the owner is not planning to take capital out of the business in the near term. All of these keep corporate and shareholder objectives aligned.

“Fast forward to the future,” Benson said. “Now you have a situation where you have an older shareholder, and they may be now looking to be more risk averse. They might even be looking to take capital out of the business, and their time horizon has become shorter. They are seeing retirement in the future.”

This can lead to a conflict when a company’s management team desires aggressive growth but older ownership is hesitant to take risks such as large acquisitions or significant capital investments.

Goodsel explained that the process of aligning corporate and shareholder objectives becomes more difficult as more people become involved.

“If you’re a single person and you own 100% share, it’s really easy to have alignment on what you want to do,” he said. “If it’s a husband-and-wife team, it gets a little more complicated; if it’s multiple partners or family members, it gets even more complicated. I think the sooner that people start thinking about these corporate and shareholder objectives, the easier they’re going to find the decision making and analysis to be.”

Bender agreed that more stakeholders increases the complexity of aligning objectives, and this can be compounded when ownership is family and personalities or rivalries threaten objective decision making.

“We really try to have some good lines in the sand between what a shareholder’s responsibility is, what the board of director’s responsibility is, and then what management’s responsibility is,” he said. “Try to make sure there’s not any meddling from the shareholder’s side into the management side because that can be really harmful to a company.”

Timing an Ownership Transition

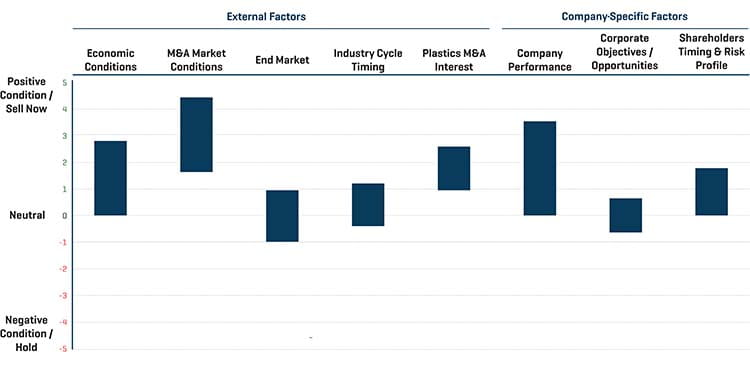

Benson explained that a combination of external and company-specific factors determines the right time for an ownership transition.

“In a perfect world, you want as many of these stars to be aligned as possible, and if that’s the case, then you’re probably in a good position to be able to do some form of a transaction,” he said.

External factors include economic conditions, the strength of both the M&A and end market, and industry cycle timing. Company-specific factors consist of the company’s performance, corporate objectives/opportunities, and the shareholders’ timing and risk profile.

“The more of these factors that are in alignment, the better, and as we all know, there are windows of time when it’s a good time to do something and there are times when it’s not,” he said. The goal for owners is to look ahead for as much alignment as possible, leading to a maximization of both value and opportunity for a company sale.

FIGURE 2: TIMING CONSIDERATIONS

Shareholder/Stakeholder Considerations

Benson explained that understanding the profile of a company’s shareholders and stakeholders will determine which strategic alternative is best. These considerations include the shareholders’ risk tolerance, the strength of the management team, the role of the family in the business, and the seller’s openness to operational changes the buyer will make. Additional factors consist of the shareholder/stakeholder timing to exit, the importance of maximizing company value, and how quickly sellers want their money.

Goodsel pointed out, with Benson’s agreement, that maximizing value in an individual- or member-owned company sale often plays less of a role than expected. The price paid for the deal will often be between a quarter million and a million dollars lower than maximum value because of other factors.

Bender recounted that in 1997 his father was looking to exit the business through selling his 50% ownership stake to the public company that owned the other half.

“As he learned what their plans were for the business and for the management team, he got cold feet and decided that wasn’t the best thing for Falcon Plastics,” he said. “It might’ve been the best thing for him, but it wasn’t the best thing for the company.”

In the end, Bender’s father purchased the public company’s ownership stake at the same price he had planned to sell his own half.

Business owners face a wide variety of strategic alternatives when it comes to transitioning their company to new ownership. Corporate considerations such as a desire for growth and capacity to take on debt interact with shareholder considerations such as timeline or liquidity concerns, and the outcome of the transition will have a significant impact on the future of the company and its employees. Business owners who see such a decision coming down the pipeline, even several years away, would do well to begin planning to ensure they have the time to identify and execute the ideal strategic alternative for their specific situation.