How Changes to the Corporate Tax Code Could Impact Business Valuations

How Changes to the Corporate Tax Code Could Impact Business Valuations

The proposed rate reduction may have cascading effects on C corp valuations, and executives should consider four key factors for corporate governance purposes.

After 31 years, the United States tax system appears headed for an overhaul. A cornerstone of the current administration is to completely transform the current tax system.

As it stands, C corporations in the United States are currently among the highest-taxed in the developed world, with a top marginal corporate tax rate of 35% on worldwide income, while pass-through entities (e.g., S corporations, LLCs) are taxed at the individual tax rate level. The current draft tax reform proposes a reduction of the top marginal corporate tax rate to 15% and moves to a territorial system for taxing multinational corporations. Another major proposed change would be the reduction of the income tax rate on small and medium-sized pass-through entities. As a result of these changes, certain special-interest tax breaks would be eliminated. In addition, the draft tax reform plan includes a one-time repatriation of all foreign earnings held by international subsidiaries.

While the current administration is proposing comprehensive tax reform (i.e., also including reforms to individual tax rates and laws), the focus herein is solely related to potential changes to the valuation of C corporations using the Income Approach as a result of tax reform. Furthermore, the valuation impacts discussed herein are limited to an enterprise-value level and therefore are reflective of a cash-free and debt-free basis.

A significant change to the corporate tax code will have cascading effects on the valuations of corporations and their reporting units and legal entities. The most notable impact will be on the discounted cash flow (DCF) method and on components of a company’s weighted average cost of capital (WACC).

As corporate tax reform continues to move forward and evolve, a wide array of questions and considerations, from both the company’s management team and the valuation team, will need to be taken into account. The following is a discussion of key items and what impact will most likely result from corporate tax reform.

How Tax Rate Affects the DCF Method

Free cash flow

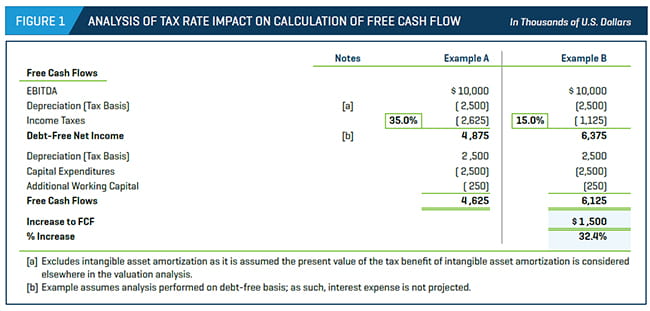

In the DCF method, a form of the Income Approach, the enterprise value of a company is estimated by discounting the projected future free cash flows of the company using an appropriate discount rate. Conceptually, free cash flow represents the cash generated by a company that is available to its investors without impairing current or future operations. As shown in Figure 1, free cash flow is calculated by: 1) reaching debt-free net income by subtracting depreciation and income taxes from earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA), 2) then adding back noncash items (i.e., depreciation), 3) subtracting cash outflows associated with capital expenditures, and 4) adjusting for cash inflows/outflows related to changes in net working capital. Therefore, a lower tax rate leads to increased debt-free net income and, thus, results in increased free cash flows.

Discount rate

Once projected free cash flows have been calculated, the next step is to discount the free cash flows to their present value equivalent using a rate of return (i.e., WACC) that reflects the relative risk of investment and the time value of money. The WACC is an overall discount based on the required rates of return for debt and equity capital weighted in proportion to their representation in a selected capital structure.

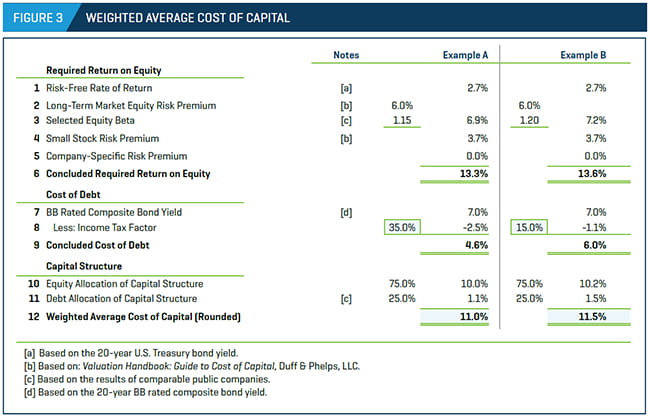

The tax rate impacts two specific components of the WACC: 1) the unlevering and relevering of the equity beta used, in part, to calculate the required return on equity, and 2) the cost of debt, which is on an aftertax basis, as interest payments are tax-deductible.

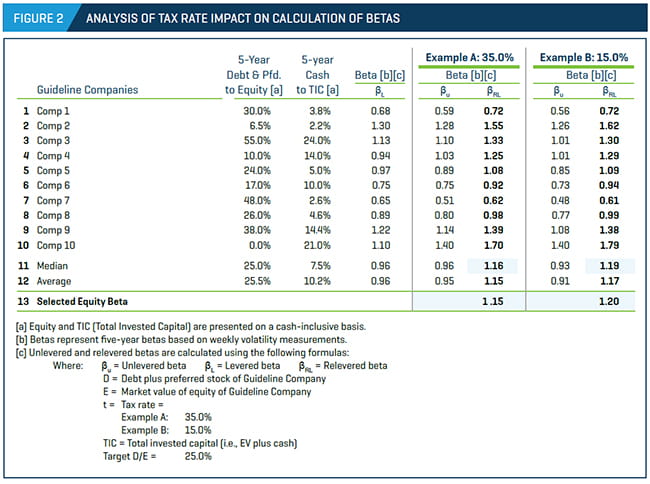

As shown in Figure 2, all else held constant, a lower tax rate results in a higher relevered beta. The primary reason for unlevering and relevering the betas of the selected guideline public companies is to better compare the market betas using the selected leverage factor in the analysis to determine the appropriate beta for the subject company. However, a change in tax rate (all else held constant) can lead an analyst to select different betas depending on the applicable tax rate. As shown in Figure 2, if an analyst determines that the selected beta should approximate the median indicated levered beta, then the analyst would reasonably select varying betas under different tax rate scenarios.

The second portion of the WACC that is affected by the tax rate is the cost of debt. The cost of debt is the rate that a prudent investor would require to lend money to a company on an aftertax basis, as interest payments are tax-deductible. All else held constant, tax rate is inversely correlated with the aftertax cost of debt. That is, the higher the applicable tax rate, the lower the aftertax cost of debt. As shown in Figure 3, a decrease in the applicable tax rate (all else held constant) indicates a higher concluded WACC as a result of increases to both the cost of equity and debt.

Other considerations

In addition to the impact that a change in the selected tax rate has on a valuation analysis with regard to the calculation of free cash flow and the WACC, there are other portions of a valuation analysis on which a change in tax rate can have a material effect, specifically the tax amortization benefit (TAB) and the net operating loss (NOL) carryforward tax benefit.

Tax amortization benefit

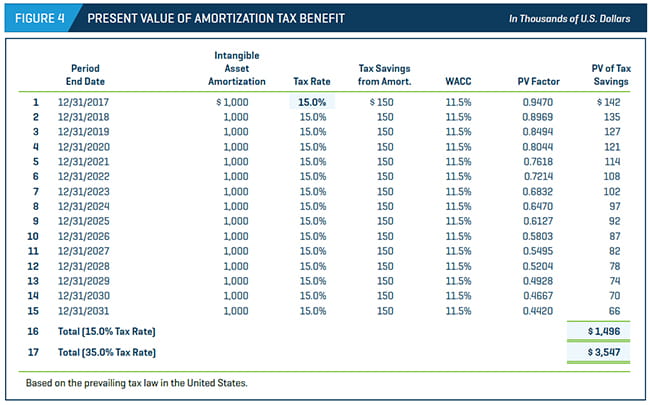

The TAB is the net present value of income tax savings resulting from intangible asset amortization. While calculating the TAB for inclusion in a valuation analysis is not always applicable (as a result of both company-specific factors and country-specific/situation-specific elections), it is important to note the impact that a change in tax rate would have on the present value (PV) of the TAB. Specifically, the tax rate and TAB are positively correlated.

Figure 4 is an example of calculating the PV of the TAB utilizing the proposed 15% tax rate as well as the current 35% tax rate (all else held constant).

NOL carryforward tax benefit

During periods when a company’s permissible tax deductions are greater than its taxable income, a company can create an NOL carryforward. NOL carryforwards can be used in future periods (i.e., typically through the creation of deferred tax assets) to offset taxable income, which serves to reduce future taxes. If a company determines that it is likely that some (or all) of a deferred tax asset will not be realized, a valuation allowance must be recognized.

As with the TAB, not all valuation analyses incorporate the tax savings benefit associated with an NOL carryforward. However, it is important to note the impact that a change in tax rate would have on the determination of the PV of the NOL tax savings. As with the TAB, tax rate changes and the corresponding NOL tax savings are positively correlated.

Key Considerations and Takeaways for Corporate Governance

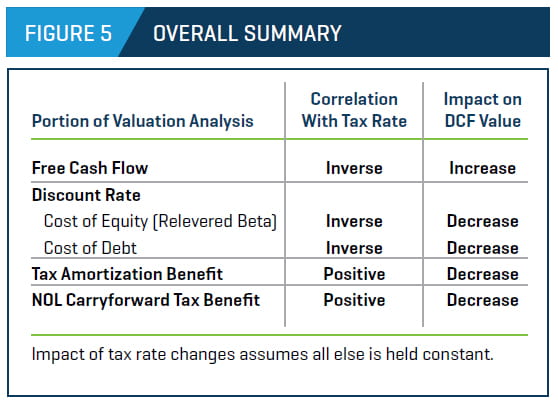

As shown in Figure 5, a lower tax rate (all else held constant) results in an increase to free cash flows, relevered beta, and cost of debt, whereas a lower tax rate (all else held constant) would result in a lower present value associated with the TAB and the NOL carryforward tax benefit.

So what does this all mean?

Now that we have identified the primary portions of the DCF method that are affected by a change in tax rate, it is important to understand what these value implications mean from a management perspective in terms of corporate governance considerations. Below is a list of primary considerations for company management and executives, stemming from the potential impact of the proposed corporate tax reform on a company’s value.

1. Increased free cash flow

All else held constant, a decline in corporate tax rate to 15% can result in increased levels of free cash flow. Thus, management will likely need to consider the best uses for these increased cash flows, such as revisiting dividend or distribution policies; fixed asset investment; undertaking expansionary growth projects; new product or service lines; and use of debt (discussed more in the following section).

2. Capital structure

Although the relationships between tax rates and the portions of a valuation analysis that are affected by tax rates have been identified, the actual magnitude of these value implications can be varied based on a plethora of factors. One of the most important factors in determining the specific magnitude is with regard to capital structure.

As previously discussed, both the cost of equity (specifically with regard to calculating relevered betas) and the cost of debt are affected by tax rate changes. However (all else held constant), tax rates have a greater impact on the concluded cost of debt than on the cost of equity. The pretax cost of debt is tax-affected to reach the concluded aftertax cost of debt, whereas tax rate plays a smaller role in determining the appropriate relevered beta used in calculating the overall cost of equity. Moreover, the selection of the applicable beta is a subjective exercise, whereas calculating the aftertax cost of debt is definitive in nature. Thus, valuations with a greater level of debt in selected capital structure will have a larger impact on the overall WACC.

Furthermore, it is important to consider a company’s optimal capital structure in terms of value maximization when considering the best use of increased free cash flows under the proposed corporate tax reform. In other words, a company’s management team will need to consider the value implications of decisions surrounding whether the company should take on more debt or pay down its existing debt.

3. Other fair value-related considerations

Due to the myriad factors and considerations inherent within fair value valuations, a comprehensive discussion regarding the specific implications of the proposed corporate tax rate reform on these analyses is outside of our scope. That said, management teams should consider several high-level topics related to decisions in conjunction with the proposed corporate tax rate changes.

First, the proposed corporate tax rate changes could have a significant impact on a decision surrounding the deal structure of a merger or acquisition – that is, whether the transaction should be structured as a nontaxable or a taxable transaction (i.e., a stock or an asset sale). This determination is also required in goodwill impairment valuations, and is based on the feasibility and highest economic value realized through either a stock (i.e., nontaxable) or asset (i.e., taxable) transaction. In general, deals that are structured as asset transactions allow the buyer to step up the tax basis of the acquired tangible and intangible assets to fair value, with the (typically) higher tax basis resulting in a tax shield. Because the tax rate and the TAB are positively correlated, the proposed corporate tax rate change can materially lower the value of the tax shield when assuming a step-up in tax basis with regard to a company’s tangible and intangible assets.

4. Valuation allowance

As previously mentioned, a valuation allowance must be created if a company determines that it is likely that some (or all) of deferred tax assets will not be realized. Given the proposed decrease in corporate tax rates, management may have to reevaluate its method of determining applicable valuation allowances.

Impact of Reduced Tax Rate

All else held constant, the proposed reduction is expected to benefit companies from a valuation perspective, but the ultimate impact will take time to sort out. What is known is that a major reduction in the top marginal corporate tax rate will pose different questions for both a company’s management team and valuation professionals.