The Taxing Side of Divorce: Division of Non-Qualified Employee Benefits

The Taxing Side of Divorce: Division of Non-Qualified Employee Benefits

Overview

Nonqualified employee benefit plans are often used to pay employees. However, these plans lack some of the tax benefits offered by qualified plans. For example, benefits may not be available for immediate distribution, and more important in the context of a divorce, it is often not possible to transfer the tax liability to the non-employee spouse.

Stock Options

Companies may grant employees options to buy a stated number of shares at a defined grant price. The options vest over a period of time and expire on a given date, usually 10 years after

the grant date. The employee can exercise the option at the grant price at any time over the option term up to the expiration date. The tax treatment of stock options differs based on the type of option granted.

If stock options are granted as payment for services, income may be recognized when the option is received (the grant), when the option is exercised, or upon the disposition of the option or the property acquired through exercise of the option. The timing, type, and amount of income inclusion depend on the type of option.

There are two classifications of options: statutory or qualified options — those granted under and governed by specific code sections — and nonstatutory or nonqualified options — those governed by the more general code principles of compensation and income recognition. The employer determines the type when making the option grant; tax treatment differs for the two types of options.

Non-Qualified Stock Options (NSOs)

Nonqualified stock options, sometimes referred to as nonstatutory stock options, are not taxable when granted. When an employee exercises an NSO, the spread on exercise is taxable to the employee as ordinary income. Any subsequent gain or loss on the shares after exercise is taxed as a capital gain or loss when the optionee sells the shares.

Incentive Stock Options (ISOs)

ISOs enable an employee to 1) defer taxation on the option from the date of exercise until the date of sale of the underlying shares, and 2) pay taxes on his or her entire gain at capital gains rates, rather than ordinary income tax rates. Certain conditions must be met to qualify for ISO treatment, most important of which is that the employee must hold the stock for at least one year after the exercise date and for two years after the grant date.

If the rules for ISOs are met, then the eventual sale of the shares is called a “qualifying disposition,” and the employee pays long-term capital gains tax on the total increase in value between the grant price and the sale price.

If, however, there is a “disqualifying disposition,” most often because the employee exercises and sells the shares before meeting the required holding periods, the spread on exercise is taxable to the employee at ordinary income tax rates. Any increase or decrease in the shares’ value between exercise and sale is taxed at capital gains rates.

Any time an employee exercises ISOs and does not sell the underlying shares by the end of the year, the spread on the option at exercise is a “preference item” for purposes of the alternative minimum tax (AMT).

If ISO shares are sold at a loss, the entire amount is a capital loss and there’s no compensation income to report.

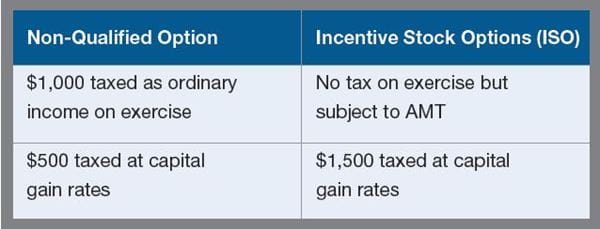

Tax Consequences of Exercising an Option

The following example illustrates the different tax consequences depending on the type of option.

- On March 1, 2013, an employee was granted options to buy 100 shares of X Corporation stock for $20 per share.

- The employee exercised the option on April 1, 2014, when the stock was selling on the open market for $30 a share.

- On May 1, 2015, the employee sold the shares for $35 a share.

Dividing Stock Options in Divorce

Immediate Cash Out One way to “divide” options is to pay the non-employee spouse the net present value of the options. The “net present value” approach results in immediate distribution to the non-employee spouse. A lump sum that represents the net present value of the future benefit is determined and may be offset by the value of other property in the marital estate. Under this method, the value of the options is determined taking into consideration different factors, including the level of risks and potential tax consequences.

The non-employee spouse may prefer an immediate distribution of his or her share of the options and be willing to forgo any future appreciation in value. The employee spouse may believe that the options will dramatically increase after the divorce.

One approach to assigning a value on stock options is to determine its “intrinsic value,” which is simply the market value of the stock, less the exercise cost of the option, applicable financing costs, and the taxes that will be assessed on the exercise. There are also more complicated mathematical formulae to determine a stock option’s present value that are beyond the scope of this article.

The employee spouse who cashes out the non-employee’s share of the options assumes the risk of an unexpected downturn in the market value of the underlying stock as in the market downturn of 2008 and 2009. Options can become worthless if the market value falls below the exercise price and the employee spouse may have paid a substantial price to keep the options.

“If, As, and When” Because most companies will not permit the options to be transferred to a non-employee, special provisions must be included in the Settlement Agreement or Judgment of Divorce to ensure that the non-employee spouse receives his or her rightful share of the options as illustrated below.

Taxation to Employee Wife and Husband agreed to divide all stock options granted to Husband as of entry of the Judgment of Divorce. A common method of dealing with the taxation of the income attributable to the exercise of the options in the judgment is as follows:

The stock options, grant dates, expiration dates, and related information is set forth on Exhibit A hereto.

Commencing upon the date of the execution of the Judgment of Divorce, Husband shall hold for the benefit of Wife, 50% of each of the granted and outstanding stock options set forth above during the time that option is exercisable.

Upon receiving written notice from Wife directing him to exercise all or any portion of the granted options held for her benefit, he shall promptly exercise such options on her behalf. In addition, any time that Husband exercises any of the aforesaid options on his behalf he shall also exercise Wife’s corresponding options on her behalf (hereinafter referred to as the “Tag Along Provision”). Notwithstanding any of the foregoing, if the shares obtained by the exercise are not to be immediately sold, Husband shall have no duty to exercise shares held for her benefit unless and until Wife provides full payment of the funds necessary to exercise them. Following the exercise of any option and sale of the associated stock on behalf of Wife, Husband shall, within fifteen (15) business days of his receipt of the proceeds, pay to Wife an amount equal to 60% of such adjusted proceeds generated therefrom. Husband shall retain the remaining 40% of the adjusted proceeds, and he shall be responsible for paying any income tax liability that may be associated with the exercise of the options on behalf of Wife. Any shortfall or over withholding of taxes shall be reconciled at the time Husband’s actual tax returns are filed based on Husband’s actual federal and state marginal tax rate at that time. Wife shall pay to Husband any shortfall within 10 days of notice from Husband. Husband shall pay to Wife any over withholding within 10 days of its determination.

This method results in the income being taxed at the Husband’s tax rate which may be significantly higher than Wife’s rate. If the employer will cooperate, the tax burden can be shifted to the Wife’s rate pursuant to several IRS rulings.

Taxation to the Non-employee In Revenue Ruling 2002-22, the IRS provided that in the event of the transfer of non-statutory stock options (NSOs) to a non-employee spouse pursuant to a divorce, the non-employee spouse should include the income resulting from the exercise of the stock options in the non-employee’s taxable income and the employee spouse could exclude the income from the employee’s taxable income. It also provided that transfers of NSOs between spouses upon divorce are not taxable events and that the recognition of income is with the spouse who receives the income upon exercise.

Revenue Ruling 2004-60 used the identical facts as Revenue Ruling 2002-22, and expanded the earlier Ruling to provide that withholding taxes and FICA (medicare taxes remain the responsibility of the employee in all cases) apply to the income recognized by the non-employee spouse with respect to the exercise of the non-statutory stock options. The employer must issue a 1099-Miscellaneous (1099-MISC) form to the non-employee and exclude the same amount from the employee’s W-2, so the income is not taxed twice. The employer withholds at the flat withholding rate of 25% that is used with bonuses.

A series of private letter rulings have expanded the IRS’s position on the ability to transfer ISOs and NSOs pursuant to divorce. Private Letter Ruling 200737009 recognized that ISOs could not be transferred without losing the tax benefits. In this case, the non-employee spouse gave the employee spouse written instructions to exercise her portion of the stock options. Even though the ISOs were never transferred to the non-employee spouse, the IRS held that the proceeds were income to the non-employee spouse and excluded from the income of the employee spouse. In order to prevent losing these tax benefits, an agreement can leave the ISOs in the employee’s name, but give the non-employee the beneficial interest and allow that individual to have a power of attorney over the account to make exercising the options simplified.

In Private Letter Ruling 200646003, the IRS held that the exercise of NSOs through written instructions from the non-employee spouse resulted in taxable income to the non-employee spouse, and the employee spouse received credit for the taxes held by the employer under the employee’s name. In this case, the NSOs were never transferred to the non-employee spouse, but were exercised at the direction of the non-employee spouse.

Restricted Stock Plans

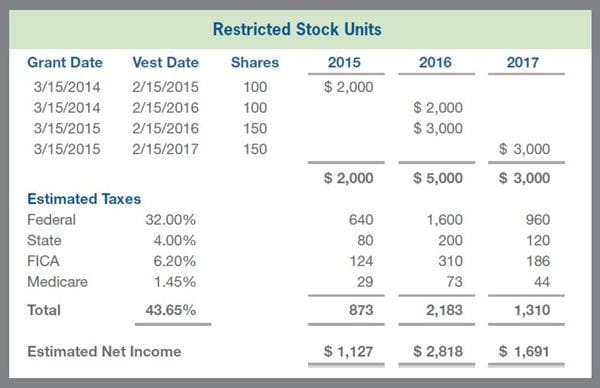

Restricted stock plans provide employees with the right to purchase shares at Fair Market Value or at a discount, or employees may receive shares at no cost. Employees cannot take possession of the shares until specified restrictions lapse. Most commonly, the vesting restrictions lapse if the employee continues to work for the company for a certain number of years, often three to five. With restricted stock units (RSUs), employees do not actually receive shares until the restrictions lapse.

Under the terms of their Settlement Agreement, Wife and Husband agreed to divide the Restricted Stock Units (“RSUs”). Further, the parties agreed that the employee would bear the responsibility for payment of the taxes and divided the net proceeds with the non-employee.

In the above example, Husband would have paid Wife $600 in 2015 ($1,000 less 40% tax), $1,500 in 2016 ($2,500 less 40% tax), and $900 in 2017 ($1,500 less 40% tax). Because Husband’s actual rate was 43.65%, Wife would owe each year for her overpayment.

As discussed above with regard to stock options, it is possible to transfer the tax liability from the employee to the non-employee.

Taxation to the Non-employee In Private Letter Ruling 2010160, the IRS ruled that the provisions of Revenue Rulings 2002-22 and 2004-60 also applied to restricted stock. In this case, a percentage of the employee spouse’s restricted stock awards were awarded to the non-employee spouse. Under the IRC, the restricted stock cannot actually be transferred, but the divorce award provided that the non-employee spouse would receive the award immediately upon vesting. This is the first ruling that held that the income attributable to restricted stock will be included in the income of the non-employee spouse.

Deferred Compensation Plans

All deferred compensation plans have a few things in common:

- Current compensation is deferred into the future.

- The method of distribution must be selected prior to the deferral. Generally, plans allow for distribution options ranging from a lump sum (one payment) to payments over time (often 5, 10 or 15 years).

- There is no income tax paid when the deferral is made.

- NQDC payments are treated as wages. When paid, NQDC payments are taxed at the ordinary income tax rates. Additionally, if Social Security and Medicare tax payments were not withheld in the year of the deferral, they will be withheld when paid.

Deferred compensation plans can also be cashed out to the non-employee spouse by valuing the entitlement at the date of divorce, net of all taxes, or can be divided on an “if, as, and when” basis using the methods described above for other nonqualified benefits.

The IRS position with regard to the transferability of assets in divorce also applies to the transfer of non-qualified deferred compensation plans. Revenue Rulings 2002-22 and 2004-60 held that the transfer to a non-employee spouse of a non-qualified deferred compensation plan was taxable to the non-employee spouse and excluded from the taxable income of the employee spouse.

Conclusion

As nonqualified benefits become more common in the workplace, it is important to identify all benefits to which a non-employee spouse may be entitled, to understand the tax consequences with such benefits, and to determine the most efficient way to provide the non-employee spouse with his or her marital share in the event of divorce.