Capital Gains Exclusion for Qualified Small Business Stock Made Permanent

Capital Gains Exclusion for Qualified Small Business Stock Made Permanent

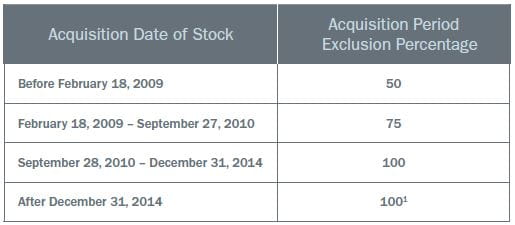

In order to provide a stimulus to noncorporate shareholders of qualifying C corporations that held their stock for a minimum of five years, Congress added Section 1202 to the tax code in 1993. Since Section 1202’s enactment 23 years ago, benefits associated with owning QSBS have waxed and waned, depending on the political climate. In some years the exclusion of gain was set at 50%, in others it was 75%, and in recent years, it was 100%. The December tax legislation, The Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act of 2015 (“PATH Legislation”), makes the exclusion permanent at 100%.

The following table summarizes these incentives:

The popularity of Section 1202 has historically suffered from two complications which made the tax benefits of the exclusion somewhat less advantageous. First, the stated rate on which the exclusion is calculated is not the current capital gains rate, 15 or 20%, but rather a 28% rate. This benchmark goes back to the top capital gains rate back in 1993, when Congress first enacted Section 1202. For example, if a taxpayer disposed of QSBS acquired prior to February 18, 2009, and recognized $10 million of gain, 50% of the gain would be excluded under Section 1202 and 50% of the gain would be taxed at a 28% rate.2Beginning in 2003, the highest marginal long-term capital gains rate was reduced to 15%. Thus, between 2003 and February 18, 2009, when the exclusion percentage was 50%, the effective tax rate on a disposition of QSBS was 14%, only a 1% savings over the then-applicable long-term capital gains rate.

The second complication was that the exclusion of gain on sale of QSBS applied only for regular tax purposes.

For purposes of computing the alternative minimum tax (“AMT”), Section 1202 characterized the exclusion as an AMT preference item. This had the effect of adding back 7% of the excluded gain to those taxpayers subject to the AMT.

The PATH Legislation has now eliminated both of the above drawbacks. With the gain exclusion now permanent at 100%, the effective federal tax rate on a disposition is zero.3 In addition, the treatment of excluded gain as an AMT tax preference item was removed.4 Taxpayers who exclude gain on the disposition of QSBS will also escape the recently enacted 3.8% tax on net investment income.5

Requirements for Characterization as QSBS

Section 1202 imposes several requirements on taxpayers who aim to take advantage of the 100% exclusion. First, the company issuing the stock must be a C corporation with $50 million or less in gross assets when the stock is issued and immediately after the stock is issued.6 Second, at least 80% of the issuing company’s assets must be used in certain active trades or businesses, including activities undertaken in the start-up period of the business, as well as research and development.7 Notable exclusions from the active business requirement include service businesses, such as in the health, law, or financial services fields. Third, the taxpayer must acquire the stock at its original issue.8 Finally, a taxpayer must hold the stock for at least five years prior to disposition.9 In our experience, almost all start-up companies satisfy these requirements. In particular, founder shares will often meet the criteria.

Capping the Benefits of the Section 1202 Exclusion

Congress has limited the benefits of gain exclusion under Section 1202. With respect to each qualifying corporation, the gain eligible for exclusion may not exceed the greater of: (i) $10 million ($5 million for married persons filing separately), less the aggregate gain excluded in prior years; or (ii) 10 times a shareholder’s aggregate basis in QSBS (the “Section 1202 Cap”).10 With respect to the calculation of basis, taxpayers are restricted from “stuffing” their basis with additional capital following the date on which they originally acquired their shares.

While many factors enter into the choice-of-entity calculus for new businesses, we have found that many clients are willing to give up certain short-term benefits in order to take advantage of potential future tax savings under Section 1202.

Although the now permanent 100% gain exclusion under Section 1202 offers welcome certainty to taxpayers, the Section 1202 Cap will significantly limit the benefits taxpayers may receive in large transactions. For example, if an individual sells QSBS and recognizes $30 million in gain, only $10 million of this gain will be excluded under Section 1202 (assuming such taxpayer’s basis in the stock is less than $1 million).

While some founders may have transferred their QSBS to key employees or investors throughout their company’s lifetime — thus potentially allowing each such employee or investor his or her own separate Section 1202 Cap — most such transfers will run afoul of the “original issuance” requirement for shares to meet the definition of QSBS.11 In limited instances, however, Congress has provided relief from this rule for certain transfers, including those that occur by gift and upon death.12 This opportunity may provide a narrow window for well advised taxpayers to multiply their Section 1202 Cap.

Application of Section 1202 to Gifted QSBS

Section 1202(h) expressly provides that, in the case of any gifts made of QSBS, the transferee is treated as if he or she acquired the stock in the same manner as the transferor (i.e., at its original issue) and that the transferee can tack the transferor’s holding period in the stock.13 While Section 1202(h) thus favorably allows gifted shares to meet the “originally issued” requirement, it is less clear whether each transferee must share in the transferor’s Section 1202 Cap or whether such transferee is entitled to his or her own Section 1202 Cap.

Under Section 1015(a), a transferee takes a carryover tax basis in gifted QSBS. Accordingly, for purposes of the Section 1202 Cap, the part of the test which measures 10x a taxpayer’s basis will effectively be shared among the transferor and each of his or her transferees. Section 1202 makes no mention, however, of whether the transferor and the transferee(s) must also share the other prong of the Section 1202 Cap: the ceiling on excluded gain of $10 million. Without any statutory or regulatory guidance, a conservative position would assert that the $10 million ceiling of the Section 1202 Cap should similarly be allocated pro rata among the transferor and all the transferees of QSBS.

Such a proportionate allocation of the Section 1202 Cap applies to a husband and wife filing separate returns, because they must each share equally in the Section 1202 Cap.14 Given the lack of similar proportionate allocation language with respect to gifts of QSBS, this omission suggests that each transferee of gifted QSBS may enjoy his or her own separate Section 1202 Cap.

This interpretation, however, could lead to significant abuse. For example, if a holder of QSBS were to gift such stock to various family members prior to a sale transaction, such transferor could effectively multiply his or her Section 1202 Cap many times. For example, if a taxpayer were to sell QSBS with a $10,000 tax basis for $30 million, her Section 1202 Cap would be $10 million, since this amount is greater than 10x the taxpayer’s basis of $10,000.15 If this taxpayer gifted two-thirds of the stock equally among her two children, would each holder of QSBS now enjoy a $10 million exclusion such that all $30 million of gain on sale could be excluded from gross income? If correct, this strategy could be aggressively deployed to substantially increase the Section 1202 Cap for family groups. No judicial authority exists on this issue, and the IRS has published no public or private rulings on this issue.

Given this dearth of available guidance, we contacted the IRS Office of Chief Counsel (“Office of Chief Counsel”) to obtain its view on this matter. We discussed the language in Section 1202(h) and the lack of any requirement for an allocation of the $10 million ceiling between a transferor and a transferee by gift. The Office of Chief Counsel informed us that it had informally addressed this issue previously and concluded that the transferee by gift should be entitled to his or her own $10 million ceiling. There was no hedging in this response; our contact clearly stated that each transferee who received QSBS by gift should be entitled to his or her own Section 1202 Cap.

The Office of Chief Counsel’s rationale for this decision was that application of gift tax on any transfer of QSBS (which currently is at a 40% rate for transfers above the unified credit limit) would significantly reduce the risk of abusive transactions. As applied to the previous example, the transferor of QSBS worth $20 million would owe a gift tax liability of roughly $5.8 million.16 Considering that the savings of capital gains tax on the transfers, pursuant to Section 1202, would have been only $4.76 million,17 the logic of the Office of Chief Counsel is persuasive. Few taxpayers would voluntarily undertake the transfers if they knew that the gift tax would far exceed the potential income tax savings.

While in this example the disincentive is strong, the planning opportunity is clear: taxpayers should gift QSBS during the start-up phase of their company, when the value is low. Had the transferor in the previous example had the foresight to make gifts to her children shortly after she formed her company, assuming a favorable valuation, the gift tax liability would have been quite low, or even nonexistent.18 Further, the transferor could have assigned non-voting stock, to ensure her continuing control over the company, which would have augmented her ability to claim a discounted valuation on the gift transfers. Had these transfers minimized the gift tax liability, then the benefits of the strategy would have been hugely successful; the transferor (and her children) would have saved an additional $5 million in combined federal and state income taxes.

Planning Opportunities

The permanence of the 100% exclusion under Section 1202 creates an additional opportunity for entrepreneurs and their advisors to consider when structuring a new venture. Typically, advisors recommend that their clients form new businesses as LLCs or S corporations, mainly so that losses from the start-up period flow through to the owner. This structure, however, does not allow the owner to take advantage of Section 1202, because the gain exclusion applies only to sales of shares in C corporations.

With the significant benefit provided by the Section 1202 100% exclusion and the opportunity to multiply the Section 1202 Cap by making properly timed gifts, forming a new venture as a C corporation may be beneficial in many circumstances. Certain entrepreneurs may be willing to trade early-year tax losses in order to save potentially substantial tax dollars in taxes on a subsequent sale of the company.

While many factors enter into the choice-of-entity calculus for new businesses, we have found that many clients are willing to give up certain short-term benefits in order to take advantage of potential future tax savings under Section 1202. The certainty provided by the PATH Legislation and the ability to “supersize” the Section 1202 Cap through a gifting strategy, now makes C corporations an attractive alternative for taxpayers to weigh when considering a new business’s legal structure.

Guest authors:

William E. Sider

Daniel Soleimani

- Section 126 of the PATH Legislation.

- IRC Sections 1(h)(4)(A)(ii); 1(h)(7). This assumes the taxpayer’s basis in the QSBS was less than $1 million. Any gain in excess of $10 million would be taxed at long-term capital gains rates.

- This assumes that no gain is recognized in excess of the Section 1202 Cap (discussed infra). To the extent excluded for federal income tax purposes, gain from the disposition of QSBS is also excluded for Michigan income tax purposes; however, other states, such as California, do not recognize any gain exclusion.

- IRC Section 1202(a)(4)(C).

- IRC Section 1411(c)(1)(A)(iii).

- IRC Sections 1202(c)(1); 1202(d). Gross assets are calculated by adding the issuing corporation’s cash on hand to the corporation’s adjusted basis in all property it holds.

- IRC Sections 1202(c)(2); 1202(e). This requirement must be met for substantially all a taxpayer’s holding period in the stock.

- IRC Section 1202(c)(1).

- IRC Section 1202(b)(2).

- IRC Section 1202(b)(1).

- IRC Section 1202(c)(1)(B).

- IRC Section 1202(h)(2).

- IRC Section 1202(h). This provision is necessary to ensure that any stock gifted still meets the definition of QSBS.

- IRC section 1202(b)(3)(A).

- IRC section 1202(b)(1).

- This assumes that the transferor has not used any portion of her unified credit amount. For a gift made in 2016, the tax owed would be [$20,000,000 (value of the gift) – $5,450,000 (unified credit amount)] * 40% (gift tax) = $5,820,000.

- The potential capital gains tax saved reflects the 20% capital gains tax applicable on the disposition plus the 3.8% net investment income tax that would also apply. As a result, the capital gains tax saved on $20,000,000 would be $20,000,000 * 23.8% = $4,760,000.

- It is possible that such transfers may have fallen within annual exclusion amount described at IRC Section 2503(b), currently at $14,000.