In Grieve Case, Tax Court Reaffirms Fair Market Value Standard

In Grieve Case, Tax Court Reaffirms Fair Market Value Standard

Stout’s appraisal of the taxpayer’s LLCs reiterated the accepted approaches to valuing minority interests in privately held investment entities.

The March 2, 2020, decision in the U.S. Tax Court Case Pierson M. Grieve v. Commissioner (T.C. Memo. 2020-28) will be one of the most talked-about cases in 2020 and is sure to be cited by practitioners for many years to come. The principal point of contention in the case dealt with the appropriate method to be used to value very large majority economic interests, in this case, 99.8% interests, where the majority interest holder possesses no voting or other rights of control in an investment holding entity. In addition to the utterly divergent valuation approaches employed by the IRS expert and the taxpayer’s expert, the case further involved arguments surrounding the applicability of the fair market value standard and the use of an income approach to value two entities holding primarily marketable equity securities and cash.

Background

Pierson M. Grieve was an exceedingly successful businessman who spent an appreciable part of his career as the Chairman and CEO of the publicly traded Ecolab. Ecolab is a Fortune 500 industrial company with an approximately $50 billion market capitalization that provides water, hygiene, and energy technologies and services to the food, energy, healthcare, industrial, and hospitality markets globally. After previously serving as an executive at the consumer goods company Questor, Grieve joined Ecolab as the Chairman and CEO in 1983 and served in this capacity for 12 years, recalling the time spent with the company as “the most successful, satisfying, and fulfilling of my 44-year career.” After his wife’s passing in 2012, Grieve and his family updated their estate plan by setting up two limited liability companies (LLCs) to act as investment entities to aggregate and manage the family’s wealth. The basic structure of the two LLCs mirrored that found in most family limited partnerships. The ownership of the two LLCs consisted of a 0.2% controlling voting manager interest and a 99.8% nonvoting interest. In this case, the 0.2% controlling voting interest was owned by Pierson M. Grieve Management, an entity controlled by Grieve’s daughter, while the 99.8% nonvoting interest was owned by a Grieve family trust. As part of an estate planning exercise, Grieve gifted the 99.8% nonvoting interests in the two entities and reported the transfers on his 709 Gift Tax Return. The IRS audited Grieve’s Gift Tax Return and proposed revised values for the transfers, which resulted in a gift tax deficiency of approximately $4.4 million.

Expert Analyses

The IRS’ Game Theory Hypothesis

In lieu of using an accepted valuation approach, the IRS expert put forth a theoretical construct involving game theory. In the IRS expert’s valuation, the hypothetical seller of the 99.8% nonvoting interests in the two LLCs would not part with their interests at a large discount to the net asset value (NAV). Rather, the IRS expert supposed that the owner of the 99.8% nonvoting interest would seek to enter into a transaction to acquire the 0.2% controlling voting interest from the current owner of that interest. Doing so would consolidate their ownership to 100% and eradicate the diminution in value resulting from lack of control and marketability.

To numerically support this theoretical construct, the IRS expert assumed that the owner of the 99.8% nonvoting interest would have to pay the controlling 0.2% voting member a premium above their undiscounted NAV. In his valuation, the IRS expert estimated that an approximate 28% discount to the NAV was appropriate for the 99.8% nonvoting units using a traditional discount methodology. Rather than accepting this discount, the IRS expert proposed that the owner of the 99.8% nonvoting interest would be willing to pay a portion of the dollar amount of the discount from the NAV to purchase the 0.2% controlling voting interest.

Using various unsupported mathematical premium assumptions, the IRS expert concluded that an appropriate discount for the 99.8% nonvoting interest would be approximately 1.5% for both entities based on speculation that giving up 5% of the dollar discount from the NAV would be sufficient to entice the owner of the 0.2% controlling voting interest to transact and sell their interest. However, it was not clear in the IRS expert’s analysis why that would be the case. In a zero-sum game theory, each rational party would seek to maximize their benefit. If that were to be the case here, as the foundation of the IRS expert’s argument proports, the owner of the 0.2% controlling interest played the game imperfectly.

By virtue of their ownership interest, the owner of the 0.2% voting interest possesses all the power to influence the value of the 99.8% nonvoting interest. Recognizing this, the owner of the controlling voting interest would seek to maximize their payoff in this zero-sum game – or attempt to come as close as possible to a 50/50 split of the implied dollar discount to the 99.8% nonvoting interest holder. Even if the owner of the 0.2% voting interest were to hold out and demand 99.9% of the dollar discount from the NAV, the owner of the nonvoting units would still theoretically be better off and engage in the transaction.

Manufactured Ownership Structures

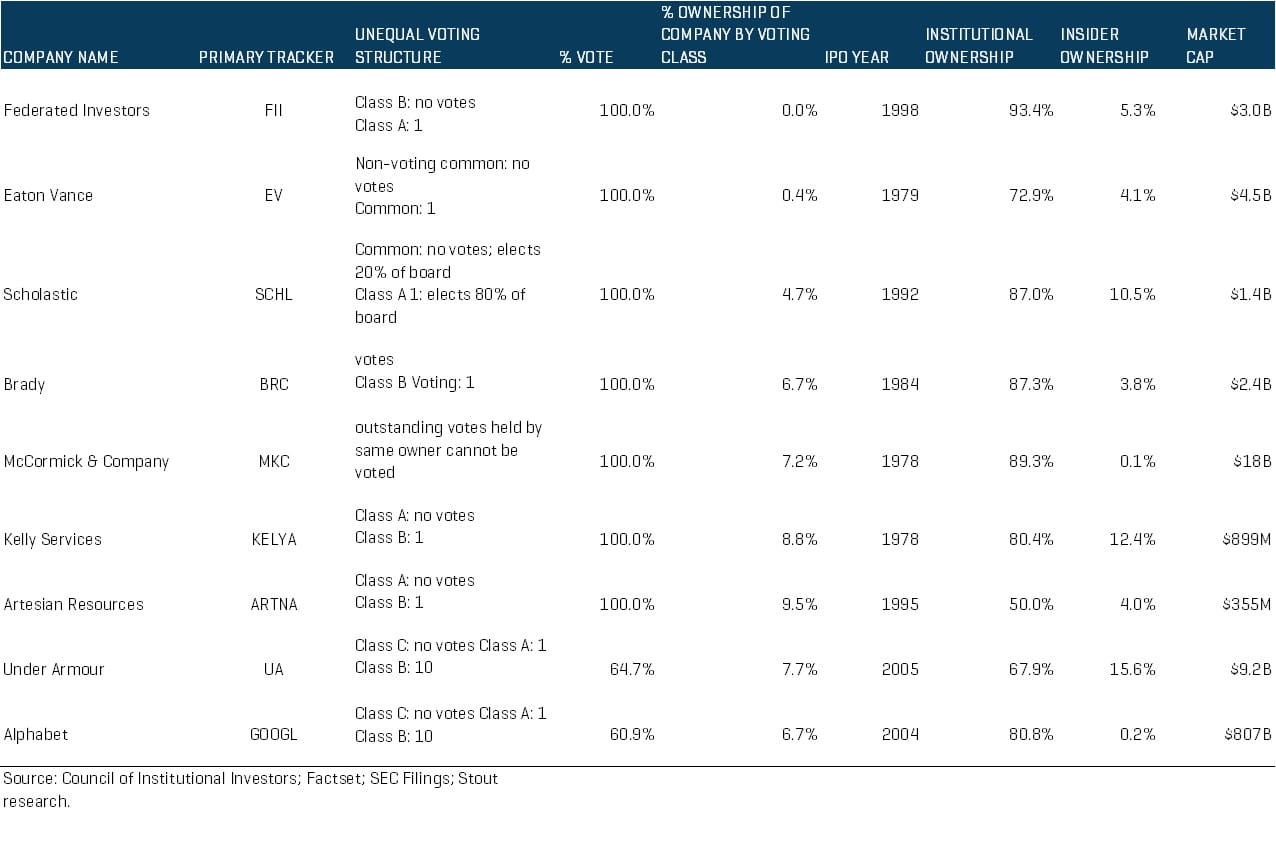

During trial, the IRS expert made the observation that such ownership structures (i.e., voting control concentrated via ownership of a small economic interest) are not something typically found outside of family entities for estate planning purposes and was further not able to answer questions about public companies that had dual-class structures in which a disproportionate amount of the vote was held by a small amount of the equity ownership. At trial, the Stout team was able to produce a document published by the Council of Institutional Investors that listed hundreds of companies – including some of the most well-known companies in the world – where a disproportionate amount of the voting power is held by one class of stock compared to another class of stock. Of the hundreds of companies identified by the Council of Institutional Investors, the Stout team produced the following subset and included additional pertinent information for each company:

As is clearly observable in the table, there are numerous publicly traded companies in operation with disproportionate ownership and voting characteristics. Eaton Vance, for example, has a voting class that owns just 0.4% of the company but has 100% of the voting power – which is not too dissimilar from the two subject LLCs in this case. Moreover, Eaton Vance is a $4.5 billion market capitalization company, and 73% of the nonvoting shares are held by institutional investors.

The Reasoned Approach of the Taxpayer’s Experts

The reports of the taxpayer’s initial expert, which were filed with the Form 709 Gift Tax Return, used a relatively standard analysis consisting of a study of closed-end funds to determine the lack-of-control discount and restricted stock studies to establish the lack-of-marketability discount. The initial expert for the taxpayer concluded that appropriate discounts were approximately 13% for lack of control and 25% for lack of marketability for both entities (with slight variations in the lack-of-control discount due to a differing asset mix between the two entities). Nonetheless, the resulting combined discount for both LLCs was approximately 35%.

Once on audit and seemingly destined for Tax Court given the large disparity in valuations, the taxpayer’s legal team brought in an expert team from Stout to perform an independent appraisal of the two LLCs. The Stout analysis similarly relied on a study of closed-end funds to determine a discount for lack of control and a detailed analysis of various restricted stock studies to establish a discount for lack of marketability (an approach known as the Market Approach). In addition to the Market Approach, the Stout analysis included entity-level discounts for certain nonmarketable investments owned by one of the LLCs and a valuation using the Income Approach for both.

In independently determining the market value of each LLC, the Stout team observed that one of the LLC’s assets included investments in private equity and venture capital investment funds managed by a third party. Recognizing that the reported capital account balances for these investments reflected a pro rata NAV, which by definition reflects a controlling premise of value, the Stout team marked these investments to market by applying a combined discount for control and marketability considerations. This adjustment resulted in a slightly lower starting NAV for one of the LLCs vis-à-vis those provided by the taxpayer’s initial expert.

The Stout appraisal also included another method to determine the fair market value of the 99.8% nonvoting interests, namely, the non-marketable investment company evaluation (NICE) method, which uses an Income Approach to value a noncontrolling interest in an entity. The NICE method, which is predicated on peer-reviewed published articles and valuation texts, is a valuation method whereby fair market value is determined by calculating the present value of a portfolio of assets by discounting them at an appropriate investment rate of return, taking into account the nonmarketable minority nature of the subject entity as well as the investment risks and duration of the investments. Giving the Market Approach and the Income Approach equal weighting resulted in a fair market value which, when compared with the NAV, resulted in a slightly higher overall discount for the entities compared to the discounts delineated in the reports originally filed with the Gift Tax Return.

Tax Court’s Findings

The IRS’ Hypothetical Game Theory

Not surprisingly, the Tax Court rejected the IRS expert’s game theory valuation approach in its entirety, concluding that any construct involving the hypothetical purchase of the voting interest was not “reasonably probable.” The Tax Court’s opinion went on to state:

“Elements affecting the value that depend upon events within the realm of possibility should not be considered if the events are not shown to be reasonably probable … The facts do not show that it is reasonably probable that a willing seller or a willing buyer of the class B units would also buy the class A units and that the class A units would be available to purchase.”

In light of such a resounding rebuke of its expert’s valuation technique, the IRS’s basis for proceeding to Tax Court with such an argument remains opaque, although not novel. It appears as though the IRS clearly believes in a "Holman-like" (Holman v. Commissioner, 130 T.C. No. 12 May 27, 2008) result where the discount comes from a negotiation of rational parties rather than a traditional view of willing seller-willing buyer. This is what was behind the “Proposed Changes to Section 2704,” which failed. Was such an argument in this case an auxiliary attempt to evoke the family attribution properties promulgated in the “Proposed Changes to Section 2704”? If not, the Tax Court merely reaffirmed the fair market value standard in valuation engagements and firmly rejected the IRS’s use of an unsupported speculative theory.

Tiered Discounts and the NICE Method

It has been noted elsewhere that the Tax Court was critical of Stout for applying “tiered discounts” in the case of the private equity and venture capital investments. Upon closer inspection, however, there is no direct support for this observation. What the Tax Court said was: “Respondent opposes these adjustments and contends that the adjustments result in multiple tiers of discounts if the [Stout] report’s valuation of Angus is accepted since his valuation includes further discounts.” This was the only mention of tiered discounts, and it is merely a quote of the IRS’s position. The Tax Court never commented directly on this issue.

Although the opinion was mostly silent on the issue of the NICE method, it is notable that the Court did not criticize the NICE method. In fact, the transcripts seem to indicate that the Tax Court was very understanding of the method. Although the IRS’ expert took issue with the 17-year holding period assumption in the approach, he supported the use of the Income Approach to value privately held investment holding entities – even indicating during the “hot tubbing” session with both experts and the Tax Court Judge that he too had previously used the Income Approach. This is perhaps a signal of acceptance of the NICE method by both the Tax Court and the IRS in future cases.

Affirmation of Fair Market Value Standard

The Grieve case will long serve as a reaffirmation of the fair market value standard and reasoned, accepted approaches to valuing minority interests in privately held investment entities. In its opinion, the Tax Court observed that the two valuation experts’ reports on the LLCs, the original valuation filed with the Gift Tax Return, and the expert report provided at trial used similar approaches and methodologies. Ultimately, the Tax Court opined that it saw no reason to depart from the original valuation conclusions of value that were filed with the Gift Tax Return, likely gaining comfort from the two experts’ similar approaches and relatively close value conclusions.