Rule 144A and the Imaginary Market in Restricted Stocks

Rule 144A and the Imaginary Market in Restricted Stocks

In the gift- and estate-tax world, valuation analysts often rely on transactions in restricted stock to determine the appropriate discount for lack of marketability applicable to a minority interest in a closely held company. In doing so, we first must ask the question — All else equal, should the stock of a company that is not traded in the public market be valued differently than the stock of a company that is? Naturally, we look to empirical evidence in the markets for an answer and find that public companies do sell shares that are, for a limited time, restricted from trading in the public market. Such sales generally occur at a discount from the publicly traded price. The next question then is — What magnitude should that discount be? To answer this question, we need to understand what factors impact the discounts observed in the restricted-stock transactions. This topic has been widely discussed and a multitude of factors have been identified. Generally, these factors fall into the broad categories of holding period, riskiness of the underlying business, and distributions. We will focus on the holding period as it relates to Rule 144.1

Rule 144 imposes a “required” holding period — the time the buyer of the restricted stock has to wait until such shares can be resold in the public markets. This required holding period has changed over time due to changes in Rule 144. Prior to the expiration of the holding period, such buyer can resell the restricted shares in a private transaction. However, the buyer in a private transaction would inherent the same problem in terms of legal restriction before a public sale is permitted. As a result, any such private transaction generally also occurs at a discount from the publicly traded equivalent price. In addition to the initial required holding period, additional Rule 144 restrictions related to affiliate restrictions, as well as practical volume limitations due to the size of the block relative to daily trading volume may further prevent the restricted shares from being sold immediately in the public markets. The dribble-out provisions of Rule 144 require large blocks of restricted stock to be sold over time, resulting in an “effective” holding period that could be much longer than the minimum “required” holding period under Rule 144.

Although both restricted public stocks and an interest in a privately held company could be sold in a private placement, the market for privately held interests is significantly less developed than the market for restricted public securities. With respect to the holding-period concept, restricted stocks have a great advantage over a privately held interest. The effective holding period represents the relatively near point of time when the shares of the restricted stock can be freely sold on a public stock exchange. After the end of the minimum required holding period, and subject to satisfying other Rule 144 requirements, restricted stocks become freely tradable in the public market. On the contrary, privately held interests are not governed by Rule 144 and there is no opportunity to sell on an efficient public market exchange. Unlike the shares of restricted stock, privately held shares are, in effect, forever constrained from selling in the open public market, thus relegating them to the private market as their only option for sale. The “effective” holding period for an interest in a privately held company is defined as the time period until that company reaches an event that provides similar liquidity, such as an IPO or outright sale of the business. In some case, there may never be such a liquidity event.

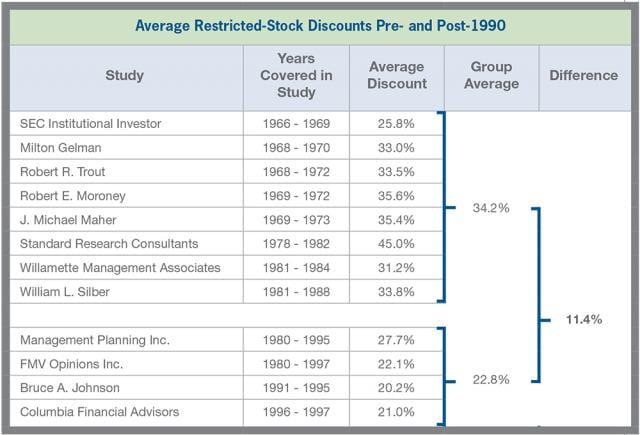

Because the effective holding period of private company stock is usually much longer than the required holding period of the restricted stocks, appraisers typically look at transactions in restricted stock that have the longest effective holding periods. Accordingly, the older restricted-stock studies are most relevant. Within these older studies, the larger block transactions are most relevant since these transactions would reflect the longest effective holding period.

The required holding period under Rule 144 has decreased over time. Prior to 1990, the required holding period was two years and “tacking” was not permitted, meaning any buyer of such stock in a private transaction would have to wait another full two years before being permitted to resell the stock in the public markets no matter how long the previous owner held the stock. With the adoption of Rule 144A in 1990, the tacking provision was eliminated. In 1997, the required holding period was reduced to one year and, in 2007, the required holding period was decreased to six months. With each relaxation of Rule 144, the average private-placement discount declined.

We have often observed the argument that, in 1990, when Rule 144A was adopted, it created a limited market for restricted stocks by allowing such stock to be bought and sold between institutional buyers. Furthermore, some analysts have argued that the difference between the discounts observed in the pre-1990 transactions and post-1990 transactions (about 11% to 12%, depending on which studies are considered) reflects the pure discount for lack of marketability and that any discount observed in the post-1990 transactions is due to factors unrelated to marketability. In the Holman case, for example, the Tax Court adopted a 12.5% marketability discount based on a similar analysis presented by the valuation expert retained by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).2

However, these arguments are flawed. The market for restricted stocks created by Rule 144A is more imaginary than real. There was no more of a market for shares of restricted stock of U.S. corporations after the passage of Rule 144A than there was before its passage. In an extensive article entitled “The Birth of Rule 144A Equity Offerings,” William K. Sjostrom Jr., Associate Professor, Salmon P. Chase College of Law, Northern Kentucky University,3 reviews the evolution and history of Rule 144A as it relates to restricted stocks of U.S. corporations. In his article, Mr. Sjostrom notes, “the Commission adopted Rule 144A in 1990 to spur further development of the U.S. private placement market…The chief innovation of Rule 144A was to decrease this illiquidity discount by providing institutional investors a regulatory avenue for the immediate resale of privately placed securities. While the resulting Rule 144A private placement market started off slowly, it has since exploded. NASDAQ estimates that over $1 trillion of debt and equity capital was raised in 2006 through 144A offerings, reflecting a 300% increase since 2002.”

Importantly, Mr. Sjostrom then qualifies his comment. “Combining debt and equity capital into one figure is somewhat misleading in that it gives the wrong impression as to the size of the equity capital component. In fact, the overwhelming majority of capital raised under Rule 144A consists of debt because Rule 144A’s “non-fungibility” condition generally prevents U.S. public companies from undertaking Rule 144A equity offerings. Foreign firms, however, have routinely relied on Rule 144A to issue equity in the U.S.”

This observation is corroborated by Harold S. Bloomenthal in the Securities Law Handbook4 in which he states, “For most reporting U.S. issuers, the exclusion of fungible securities limits the Rule 144A market to debt securities.” According to the Commission’s own staff report on Rule 144A dated September 30, 1991, “…no U.S. issuer has sold common equity securities through a Rule 144A placement, although… there have been a number of Rule 144A placements involving convertible debt securities, convertible preferred stock and nonconvertible preferred stock of U.S. issuers.”

Based on the facts, a more reasoned conclusion regarding the decline in the mean discount for lack of marketability between the restricted stock studies covering the years prior to 1990 and subsequent to 1990 was that it occurred due to another change in Rule 144 made in 1990. In that year, the Commission amended Rule 144 to allow tacking of the holding period between investors. As mentioned above, prior to the amendment, if a purchaser of restricted stock were to sell his holdings in a privately negotiated transaction, the required holding period would “restart.” Thus, any buyer of the restricted stock would have to wait at least two years before he could access the public market. The Rule 144A amendment allowed the purchaser of restricted stock to “tack” the holding period of the previous owner of these securities to his own holding period, so long as the previous owner was not an affiliate of the issuer. This permitted the holding period to be measured from the time that the securities were initially purchased from the issuer or an affiliate, so that an owner may tack on to a prior owner’s holding period, rather than restarting the entire holding period for each successive owner.

This rule change had the effect of potentially advancing the date when the shares of restricted stock could be sold in the open market, thus shortening the holding period relative to what the rule required prior to 1990. This, in turn, served to significantly increase the liquidity of the restricted shares, which caused the average discounts in the studies covering the years subsequent to 1990 to decline from 34.2 percent to 22.8 percent. The rationale for the decline in the mean discount for lack of marketability between the two sets of studies is not due to the creation of a limited market, but rather the change in effective holding period.

In addition, in 1990, the Commission also eliminated the provision that previously tolled (or suspended) the holding period of the holder engaged in short sales, puts, or other options to sell the securities. This, however, is generally not viewed as impacting the decline in the mean discount significantly. It has been noted that such hedging transactions are practicable mostly for highly liquid stocks, where publicly traded options are available and/or short selling is possible. Prime candidates for such transactions are companies with market capitalization in excess of $500 million and companies whose stock trades relatively actively, more than 100,000 to 200,000 shares per day. The majority of companies in the published restricted-stock studies are not large and liquid enough to be good candidates for such hedging or sale transactions.

In conducting an analysis of restricted stock studies to determine the appropriate discount for lack of marketability applicable to a minority interest in a privately held company, it is necessary to compare and contrast the attributes that impact the magnitude of those discounts between the subject interest being valued and the subjects of the restricted-stock studies. By having a thorough understanding of the holding period restrictions and other illiquidity attributes impacting the empirical data, an analyst can be better prepared to rebut an unsupportable position presented by the IRS and provide reliable conclusions.

--

1 Rule 144 of the Securities Act of 1933 allows public resale of restricted and control securities if a number of conditions are met. Restricted securities are securities acquired in unregistered, private sales from the issuing company or from an affiliate of the issuer. Investors typically receive restricted securities through private placement offerings.

2 See Holman v. Commissioner, 130 T.C. No. 12, May 27, 2008 and Holman v. Commissioner, 105 AFTR 2 d 2010-721 (8th Cir. April 7, 2010) affirming 130 T.C. 170 (2008).

3 William K. Sjostrom Jr., Associate Professor, Salmon P. Chase College of Law, Northern Kentucky University, The Birth of Rule 144A Equity Offerings, UCLA Law Review, Vol. 56, p. 409, 2008.

4 Harold S. Bloomenthal, Securities Law Handbook, § 10:14 at 654.