Getting to 'Yes' High-Low Patent License and Settlement Agreements

Getting to 'Yes' High-Low Patent License and Settlement Agreements

Established companies frequently are involved in patent infringement disputes or are targeted by patent licensing campaigns. Companies confronted with such challenges face significant uncertainty, which can adversely affect their strategic and financial planning. Because of the potential for large damages awards, unpredictable outcomes, and lengthy, expensive lawsuits, patent infringement disputes are particularly problematic for businesses.

Predicting the outcome of a patent case is notoriously difficult. In recent years, patent owners have enjoyed 77 percent and 57 percent success rates in jury and bench trials, respectively.1 However, a large number of these verdicts have been overturned on appeal, with claim construction alone accounting for a 24 percent reversal rate between 2005 and 2011.2 Since 2012, accused infringers have successfully challenged patent validity in recently created inter partes review (“IPR”), covered business method (“CBM”), and post-grant review (“PGR”) proceedings at the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (“USPTO”). For example, IPRs have resulted in some or all patent claims being declared unpatentable in approximately 86 percent of completed trials.3 Further exacerbating the issue are continued legislative efforts at patent reform4 and recent court decisions, including many from the U.S. Supreme Court, which have modified and clarified the rules of patent litigation.5

The length and cost of patent litigation only add to the uncertainty. For example, the median time to trial for patent cases over the past decade has been approximately two years and five months,6 but some cases have lasted up to five years, including appeals. Additionally, there is a great deal of uncertainty regarding the potential for damages, with juries awarding a median damage award of $2.9 million from 2010 through 2014 and damages reaching more than $1 billion in three trials during the same period.7 Also, depending on the size and scope of the patent trial, the median cost in 2015 was between $600,000 and $5 million.8 IPR, PGR, and CBM proceedings have the potential to reduce the duration and cost of patent disputes, which are statutorily required to be completed within 12 months of institution (or up to 18 months for good cause)9 and have an average cost of less than $500,000.10 These USPTO proceedings, however, do not necessarily resolve all legal disputes in a patent case.11 The aforementioned uncertainty in the patent litigation process drives the need for a novel approach to settlement and licensing. To address this need, the Stanley Black & Decker, Inc. legal team has designed and implemented a “high-low” settlement strategy that helps businesses more accurately account for risk while preserving their ability to resolve key legal disputes. Using this alternate settlement structure, both patent holders/licensors and accused infringers/licensees can work collaboratively to reduce risks associated with patent litigation and reach a mutually beneficial agreement. This article discusses the structure of a high-low settlement, addresses some of the legal issues associated with such a deal, and provides practical tips for negotiating this type of settlement.

High-Low Settlement Structure

Although patent disputes may appear at first to comprise numerous complex issues, they often can be distilled into a smaller number of representative issues. In addition, these issues often turn on a few key legal disagreements, such as construction of a handful of patent claim terms or validity of patent claims over a few prior art references. In many of these cases, the parties’ reasonable, well-founded disagreements about the key issues are the main obstacles to settlement.Stanley Black & Decker’s “high-low” settlement structure seeks to overcome these obstacles by using those few key legal disputes as a proxy for a broader settlement agreement. The structure of this type of settlement agreement is as follows: The parties agree that, in exchange for settlement of all issues (such as a license to all the asserted patents):

- the licensee or accused infringer will make a relatively small, nonrefundable initial payment to the licensor or patent holder

- a neutral third party will adjudicate the key issues only

- depending on the outcome of that adjudication, the licensee or accused infringer will make a second, predetermined higher payment to the licensor or patent holder

Several considerations and options exist for each of the three components of a high-low settlement agreement. First, the parties must determine the amount of the small initial payment. Generally, it should be significantly less than the combined cost of litigation, potential damages, and/or the licensing fee, but still large enough for the parties to have an economic interest in the outcome. It may be helpful for this initial payment to be large enough to help defray the patent holder’s costs for the adjudication. Also, it is typically preferable to make this payment nonrefundable.

Second, the parties must agree on which of the contested patents, claims, or legal disputes to select as the proxy issues for the adjudication. For example, the parties should select only certain representative patents, claims, and/or countries, and within those only a small number of issues, such as claim construction, validity, or infringement. The selected patent claims should be manageable in number, should include both independent and fallback dependent claims, and should identify any key claim terms that need to be construed. For an invalidity challenge, the parties may wish to select and use a few representative prior art references and/or combinations.

Third, the parties must select a forum, whether private (e.g., arbitration) or public (e.g., a USPTO proceeding, such as IPR, PGR, CBM, or ex parte reexamination; or a U.S. district court proceeding, such as a declaratory judgment action), for resolving the proxy dispute. The parties should consider several factors in determining which type of forum to use. For example, a private forum preserves confidentiality and avoids invalidation of a patent as to other third parties (although the information would likely be discoverable in future litigation); public proceedings, on the other hand, place a patent at risk vis-à-vis other third parties. Furthermore, although virtually any issue can be decided in a private arbitration, a public forum may be limited to only certain issues (e.g., an IPR allows only validity challenges based on printed publication prior art). The parties should also consider the speed and cost of resolution and (as discussed next) should weigh the legal issues with respect to each forum.

Private arbitration may also require negotiation and agreement regarding the procedural and substantive rules to be used (e.g., USPTO procedural rules, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Federal Rules of Evidence, arbitration association rules such as JAMS’ and AAA’s), the number of arbitrators, how arbitrators will be selected, whether the arbitrators will issue a yes/no decision or a well-reasoned opinion, whether claim amendments will be allowed, the timing of the arbitration, and who will bear the costs (i.e., each party pays its own expenses, loser pays, or challenger pays).

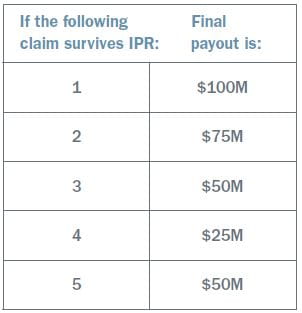

Fourth, the parties must agree on the magnitude and structure of the second payment. It should be a structured payout, with a maximum amount and various lower amounts that depend on outcome. For example, the settlement agreement may include a tiered payment structure providing that the accused infringer will make a larger payment if the surviving patent claims are broader and cover more products; a smaller payment if the surviving patent claims are narrower and cover fewer products; and/or a zero payment if all claims are found invalid. In one possible scenario, the payouts may be set forth in a table format, such as the following, which is based on the outcome of a validity challenge against claims 1-5 of a U.S. patent in an IPR proceeding:

Payment structures like this may be additive or set to a maximum amount. Additionally, parties may contemplate whether to apply running royalties and whether to give arbitrators leeway to adjust payments based on predefined guidelines.

Legal Risks Inherent In Forum Selection

Several legal risks accompany the parties’ selection of an appropriate forum. If the parties choose to have the dispute adjudicated in district court, there could be a question as to whether the case meets the “case or controversy” jurisdictional requirement. U.S. federal courts do not have jurisdiction over a case unless a genuine dispute exists between the parties,12 and they lack jurisdiction over a case that is moot, such as when the plaintiff has abandoned the claim.13 If the parties have already signed a settlement agreement, even one that is contingent on resolution of a dispute, a court may question whether the dispute truly exists. In addition, the parties may want to consider the res judicata effects of district court litigation.If the parties choose to have the dispute adjudicated in one of the newly created USPTO proceedings (i.e., IPR, PGR, or CBM), the challenging party is required to disclose which is the real-party-in-interest.14 According to the PTAB Office Patent Trial Practice Guide, a real party-in-interest is “the party or parties at whose behest the petition has been filed,” and its determination is “highly fact-dependent.”15 If the parties have entered into a settlement agreement, there could be a question as to whether the patent owner is also a real-party-in-interest in the proceeding. In addition, the parties should consider the statutory estoppel effects of filing an IPR, PGR, or CBM.16

If the parties select private arbitration, they should be cognizant of a risk that the agreement could be found unenforceable under Lear v. Adkins, 395 U.S. 653 (1969). In Lear, the Supreme Court held that it is against public policy for an agreement to bar a licensee from challenging the validity of a patent.17 The reason is that there is an “important public interest in permitting full and free competition in the use of ideas which are in reality part of the public domain.”18 If an agreement allows a validity challenge, but only in a private forum, it is possible that such a private challenge would not satisfy the public interest because the patent would still remain valid as to the general public regardless of the outcome. For this reason, it is suggested that any high-low settlement agreement that specifies a private forum also include a clause allowing the licensee to challenge the patent’s validity in a public forum at the expense of losing the license.

Precursors to Negotiating a High-Low Settlement

Parties poised to negotiate a high-low settlement will find it helpful to take several steps ahead of time. Before starting the negotiation, it is beneficial to enter into a confidentiality and standstill agreement. Many parties rely solely on Federal Rule of Evidence 408, which states that offers and statements made during settlement negotiations are inadmissible in U.S. federal courts. This rule alone, however, is insufficient because the evidence may be used in later litigation to impeach witnesses. In addition, the rule may not apply in USPTO proceedings or in foreign proceedings, and it does not put a hold on litigation or validity challenges. In contrast, a confidentiality and standstill agreement may stay all current litigation and proceedings, prohibit either party from initiating further litigation or proceedings for a predetermined period of time, provide that all discussions and information exchanged remain confidential and be prohibited from use in any forum, and set a time limit and structure for the negotiations.

Once the parties have entered into a confidentiality and standstill agreement, they can feel comfortable freely exchanging their legal positions and views on the case. During the initial stages of these discussions, the parties may exchange positions on claim construction, invalidity contentions, and infringement contentions. These discussions often reveal that the outcome of the case may be contingent on a few key issues, about which the parties cannot easily resolve their disagreement. At this point, one party may suggest the high-low settlement structure.In order for this licensing structure to work, the parties must establish some level of trust. This type of settlement negotiation therefore tends to work better when the parties act rationally and have mutual interest in settlement (e.g., the parties are competitors in an industry). The high-low structure may not work as well with non-practicing entities looking for a quick nuisance payment, with parties that have a greater emotional investment in their case, or if one party is seeking an injunction.

Conclusion

Under the right circumstances, a high-low settlement agreement can be beneficial to all parties involved. Defendants/licensees often like the high-low settlement structure because it places a cap on their maximum out-of-pocket costs, reduces the legal expenses to resolve the dispute, shortens the duration of the dispute, and offers greater certainty during what can be an unsettling process. Plaintiffs/licensors tend to like the high-low settlement structure because it guarantees at least a small licensing fee, reduces discovery costs, and simplifies the issues for litigation. Even though it leaves certain legal issues to be decided by a third party, this type of settlement agreement reveals the maximum potential future liability and risk upfront, enabling businesses to better plan for the future. By accounting for this liability, businesses can move past the legal dispute and focus on more vital activities. When parties in a patent infringement case agree to implement a high-low settlement structure, getting to “yes” can be a much smoother, far less uncertain process.

Guest Author:

Scott B. Markow, J.D.

- Ronen Arad, Landan Ansell, Chris Barry, Meredith Cartier and HyeYun Lee, “2015 Patent Litigation Study: A change in patentee fortunes,” PWC 9 May 2015: 9.

- J. Jonas Anderson and Peter S. Menell, “Informal Deference: A Historical, Empirical, and Normative Analysis of Patent Claim Construction,” Northwestern Law Review 108 Rev. 1 2013: 40.

- “Patent Trial and Appeal Board Statistics,” United States Patent and Trademark Office 30 Nov. 2015: 9.

- Pauline Pelletier and Eric Steffe, “What To Know About Patent Reform Bills Heading Into 2016,” Law360, 17 Jan. 2016

- See, e.g., Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. V. CLS Bank Int’l, 134 S. Ct. 2347 (2014) (claims directed to abstract idea ineligible for patent protection under 35 U.S.C. § 101); Limelight Networks, Inc. v. Akamai Technologies, Inc., 134 S. Ct. 2111 (2014) (induced infringement requires direct infringement by a third party); Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc., 134 S. Ct. 2120 (2014) (claims are indefinite if they “fail to inform, with reasonable certainty, those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention”); Octane Fitness, LLC v. Icon Health & Fitness, Inc., 134 S. Ct. 1749 (2014) and Highmark Inc. v. Allcare Health Management, Inc., 134 S. Ct. 1744 (2014) (clarifying standards for attorney fee shifting to make attorney fees easier to obtain); Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. v. Sandoz, Inc., 135 S. Ct. 831 (2015) (factual issues underlying claim construction reviewed for clear error); and Cuozzo Speed Technologies, LLC v. Lee, Case No. 15-446 (S. Ct. October Term 2015) (petition for certiorari granted on question of whether broadest reasonable interpretation is correct standard of claim construction in IPR).

- Arad, Ansell, Barry, Cartier and Lee, 14-15.

- Arad, Ansell, Barry, Cartier and Lee, 4-5.

- Richard Goldstein and Donika Pentcheva, “Report of the Economics Survey 2015,” AIPLA June 2015: 37.

- “Major Differences between IPR, PGR, and CBM.” United States Patent and Trademark Office, Department of Commerce, 11 Jan. 2016

- Goldstein and Pentcheva, 43.

- IPR proceedings are limited to invalidity challenges based only on printed publication prior art. PGR proceedings allow challenges on other bases, such as 35 U.S.C. § 101 and § 112. None of these proceedings allow for determinations of infringement or damages.

- Friends of the Earth v. Laidlaw Environmental Services, Inc., 528 U.S. 167, 180 (2000).

- Pacific Bell Telephone Co. v. linkLine Communications, 555 U.S. 438, 446 (2009).

- 35 U.S.C. § 312(a)(2) and § 322(a)(2).

- Office Patent Trial Practice Guide, 77 Fed. Reg. 48756, 48759 (Aug. 14, 2012).

- 35 U.S.C. § 315(e) and § 325(e).

- 395 U.S. at 670.

- Id.