Earnout: Short-Term Fix or Long-Term Problem?

Earnout: Short-Term Fix or Long-Term Problem?

In times of economic depression or recession, one indicator of a possible recovery can be an increase in the number of merger and acquisition transactions. As the number of merger and acquisition transactions increase, disputes arising from these transactions are also likely to increase.

Post-acquisition disputes generally fall into three categories: post-closing/purchase price adjustments; breaches of representations and warranties; and earnout disputes. In this article, we focus on earnout disputes, including the following main topics:

- Definition of an earnout

- Description of the mechanics of typical

earnout arrangements - Types of earnout disputes

What is an earnout?

An earnout is a provision within a purchase agreement, or a separate agreement which is part of a collective body of transaction documents in a merger or acquisition. It makes a portion of the purchase price contingent on the acquired company reaching certain financial or non-financial milestones during a specified period after closing.1 As discussed further below, the milestones are commonly based on financial benchmarks, which include but are not limited to revenue, net income, or EBITDA.2 Buyers and sellers commonly use earnout provisions to bridge the gap between their respective views regarding the value and/or future outlook for the target company. Earnouts can be especially appropriate when the seller will continue to manage the target company and/or the target company will continue to operate on a stand-alone basis during the earnout period.

Earnouts provide potential advantages and potential risks for both sellers and buyers. Potential advantages for the seller can include:

- The opportunity to realize full value or a greater amount from the sale of the business

- When the seller will continue to work in the business during the earnout period, earnouts may provide the seller with some control over possible outcomes

- Potentially increases the salability of the business in periods of economic decline

Potential risks for sellers can include:

- Limited control over the operations of the business during the earnout period

- Restricted access to the records of the business post-closing

- Potential manipulation of the earnout calculation by the buyer with the seller’s ultimate value received

- Potential comingling of the purchased business’ interest with other buyer-owned entities during the earnout period

Potential advantages for the buyer can include:

- Aligns the risk of achieving the seller’s optimistic projections with the seller’s ultimate value received

- Reduces the amount of consideration due from the buyer at closing

- Potentially provides assurance that the buyer has received the bargained for value of the target

Potential risks for buyers can include:

- Potential manipulation of earnout calculation by the seller

- Possibly compensating seller for business improvements made by the buyer post-closing

- If the seller continues to work in the target company, the potential for the seller to sacrifice the long-term interest of the company for short-term maximization of his or her earnout payout

In addition, there are other considerations relating to the inclusion of an earnout provision in an acquisition transaction that should be considered by both the buyer and seller. These include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Earnouts can be difficult to negotiate and administrate as it can be challenging to account for and appropriately consider all potential circumstances that will affect the earnout calculation and related payout

- Increases the potential for post-acquisition disputes

- In the event the seller and key personnel will continue to be active in the target company post-closing, the likelihood of a successful integration of the seller and key personnel into the buyer’s organization

The Mechanics of an Earnout

How does an earnout work? Typically, earnout provisions are structured in the transaction agreements to be predicated upon achieving certain targets or benchmarks over a fixed period post-transaction. If the targets or benchmarks are achieved, an earnout payment is due the seller.

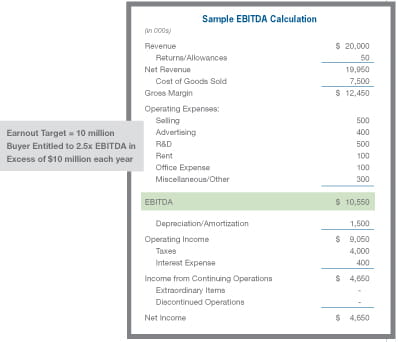

Benchmarks and Targets. The most common financial benchmark or target in an earnout provision is EBITDA. The following chart provides a simplified example of an EBITDA calculation for purposes of this article:

The seller typically prefers to use a benchmark at a high level of financial reporting, such as gross revenue. This is the measurement in the seller’s view that is least likely to be influenced by the buyer’s operation of the company post-transaction. The buyer desires a benchmark at the lowest level of financial reporting, i.e., after all expenses, such as net income. In the buyer’s view, this target accounts for all the nuances of business operation. EBITDA is, in essence, viewed to be a mid-point in negotiation between the parties, which is why it is a common measurement in earnout agreements.

Benchmarks or targets other than EBITDA, or in conjunction with EBITDA, may also be utilized. These may be industry specific, company specific or other unique measurements important to the parties. Examples include gross or net sales levels, governmental approval for products or product lines, a quantifiable successful launch of a new product, and achievements in research and development.

The term of the earnout agreement is for a fixed post-transaction period. It is typically for a one- to three-year period, which allows the buyer to assimilate the company into its operations, possibly with the seller’s ongoing assistance. It is uncommon to extend beyond three years, as at that point, the buyer should be realizing the value of its acquisition and the transitory period is over.

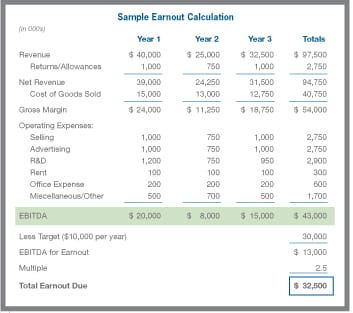

Calculation of an Earnout. The calculation of an earnout payment due the seller is geared specifically to the achievement of the benchmarks and targets. For instance, the actual payment calculation may consist of a multiple of EBITDA, a percentage of sales, or a fixed amount. In the previous example, the seller was entitled to a payment of 2.5 times EBITDA over $10 million, measured each year but payable on a cumulative basis at the end of year three. Assuming the company generated $20 million of EBITDA in year 1, $8 million in year 2, and $15 million in year 3, the seller would receive an earnout of $32.5 million at the end of year three. See the following chart for the calculation.

Types of Typical Earnout Disputes

Earnout targets and provisions are defined in the transaction agreements. From our experience, many transactions contain very specific and well-structured targets and provisions, while others are somewhat general. The more the earnout provisions in the agreement are open to interpretation, the more likely a dispute may arise. Earnout disputes can be generally categorized in two ways: Disputes as to whether the targets contained in earnout provision were met; and disputes as to why earnout targets were not met. These disputes fall into three general measurement groupings: operational issues (post-closing); accounting issues (post-closing); and the measurement of the company’s post-closing performance as it pertains to the earnout agreement.

Business Issues (post-closing). Much of the time, the buyer operates the company independently from the seller’s efforts. In an earnout dispute, the seller may have issues regarding how the buyer operated the company post-acquisition, resulting in a lower earnout payout, or eliminating it altogether. Common types of business issues from the seller’s viewpoint include the following:

- Intentionally operating the company so as to minimize a possible earnout, i.e., decreasing sales or increasing expenses

- Failure to pursue legitimate or potential opportunities

- Deviation from pre-acquisition historical or normal practices

- Loss of customers or a shift of customers to other related entities

- Discontinuation of the business in whole or in part

- Failure to obtain governmental approvals

- Failure to obtain and/or protect intellectual property

- Failure to adequately invest in operations

- Employee turnover, especially key employees

In certain transactions, the seller either continues to run the business or provides consulting services to the company during the earnout period. The buyer may have issues with how the seller continues to operate the business if he or she minimizes expenses or overstates revenue. This would inflate EBITDA or the earnout in the short term while potentially harming the company in the long-term. Examples include:

- Failure to properly maintain or replace necessary equipment

- Performing out-of-the-ordinary course of business, such as selling assets or failing to invest in R&D

- Failure to retain key customers and suppliers

- Overstating collectible sales

- Inappropriate workforce reductions

Accounting Issues (post-closing). Disputes may arise regarding the accounting methodologies used by the buyer post-transaction. Common phrases found in earnout agreements include “in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, or GAAP,” and “consistent with historical operations,” or “consistently applied.” These provisions indicate that the company, post-transaction, will continue to apply the same GAAP methodologies in place prior to the transaction, or if the company reports financial results using an allowed deviation from GAAP, the company will continue to use the historical methodology for purposes of determining the earnout.

Disputes arise when the buyer adopts an alternative reporting method that deviates from GAAP or the consistent application of the seller’s historical reporting policies. A second type of dispute may arise when GAAP changes or is modified and whether the buyer applies it or not for financial reporting and earnout purposes.

Measurement of the Company’s Post-Closing Performance. Disputes often arise as a result of what should or should not be included when measuring the company’s performance post-transaction, and how those measurements impact the earnout calculation. Examples include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Capital investments or divestitures made post-transaction

- Depreciation/amortization expense

- Discontinued operations and extraordinary items

- Goodwill amortization

- Intercompany transactions, especially pertaining to sales and cost of goods sold

- Expense allocations from the parent or other subsidiaries to the financial results of the company

Measurements of the company’s performance post-transaction are the most common types of earnout disputes that arise when combining the company with the buyer’s operations. Any change in financial measurement can affect an earnout calculation predicated on the financial results of the company.

Conclusion

An earnout provision can be a useful tool in a merger/acquisition transaction in bridging the gap between the views of the buyer and seller regarding the value of the target company. However, because of the challenges in negotiation and drafting earnout provisions that encompass all possible variables and earnouts’ inherent vulnerability to manipulation by the buyer or the seller, the calculation and payout of earnouts commonly result in post-acquisition disputes. When disputes relating to earnouts arise, the involved parties should consult with legal and financial professionals as early in the dispute process as possible.