A Taxonomy of Tracing Rules: One Size Does Not Fit All

A Taxonomy of Tracing Rules: One Size Does Not Fit All

Examining the most commonly accepted equitable tracing methods in bankruptcy proceedings.

This article was republished with permission from the ABI Journal, Vol. XXXVII, No. 9, September 2018.

The American Bankruptcy Institute is a multi-disciplinary, nonpartisan organization devoted to bankruptcy issues. ABI has more than 12,000 members, representing all facets of the insolvency field. For more information, visit abi.org.

Also contributing to this article:[1]

Jack Carriglio

Cozen O'Connor

+1.312.474.4477

jcarriglio@cozen.com

Imagine that a client has deposited $1 million to a surety company as collateral guaranteeing the fulfillment of promised services. The surety company has agreed to return the $1 million as soon as your client renders the services guaranteed by the collateral. Unfortunately for your client, the surety company goes belly up before completion of the services that your client had paid it to guarantee.

You immediately help your client change surety companies, but what about the $1 million cash collateral your client deposited into the bankrupt surety company’s account? Where did that money go? Can you recover it for your client? How will you distinguish your client’s funds from all the other money in the surety company’s account at the moment it went bankrupt? Can you trace your client’s deposit and argue for the imposition of a constructive trust on property purchased with your client’s collateral?

These are the kinds of questions that lawyers and judges must grapple with in disputes where one person’s property becomes comingled with another’s. Because money is fungible — one person’s dollar is the same as any other person’s dollar — the source of funds is difficult to trace once it has been deposited into a single comingled account. However, this does not mean your client’s $1 million is necessarily lost — not yet, anyway. You might be able to invoke one of several tracing methodologies to reconstruct where your client’s money went, and argue that your client is legally entitled to recover it.

Civil courts throughout the U.S. have endorsed and invoked a range of tracing methodologies in order to identify comingled property when specific identification is not feasible. Contrary to what its name suggests, certain tracing methodologies do not permit practitioners to separate out untainted funds from tainted ones, or follow the progress of a specific deposit from one account to another. Rather, these methodologies offer an equitable substitute for this difficult task. The Tenth Circuit has stated that “the goal of ‘tracing’ is not to trace anything at all in many cases, but rather [to] serve ... as an equitable substitute for the impossibility of specific identification.”[2] The most commonly accepted equitable tracing methods are (1) the lowest intermediate balance rule (LIBR), (2) pro rata distribution, (3) first in, first out (FIFO) and (4) last in, first out (LIFO).

Lowest Intermediate Balance Rule

In the context of bankruptcy law, the LIBR method assumes that the debtor spends its funds before spending the creditor’s funds. To the extent that the balance in the account remains at or above the amount of tainted funds contributed, those funds shall be available to the creditor (s). Tainted funds might be the proceeds from a Ponzi scheme or generated from liquidating collateral, whereas untainted funds would be considered clean and disconnected from the tainted funds.

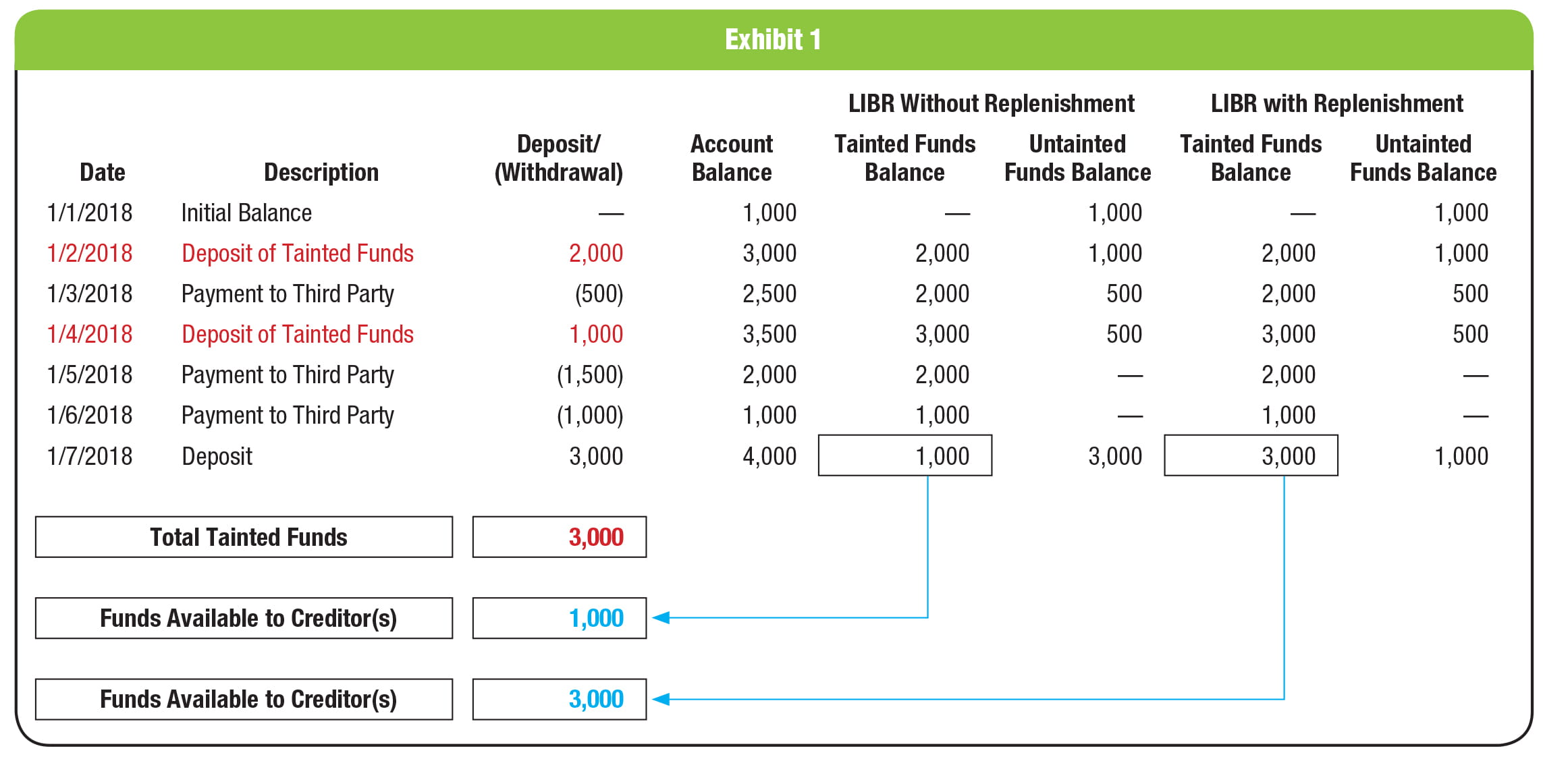

A trustee could apply the LIBR method in asserting a preference or fraudulent transfer in an effort to claw back the tainted funds and make them available for an ultimate creditor distribution. Once the tainted funds are depleted, then no subsequent deposits will replenish the funds available to creditors.[3] However, some courts have held that should the tainted funds balance drop below the total tainted funds contributed, then any new funds — regardless of their character — will replenish the tainted balance.[4] There is some dispute as to how subsequent untainted funds affect the tainted funds once those tainted funds fall below their original balance. Exhibit 1 provides a rudimentary example of the LIBR method and compares where replenishment is recognized with where it is not recognized. As shown, these methods produce dramatically different results.

Multiple circuits have endorsed the use of the LIBR method in bankruptcy proceedings. For example, the Eighth Circuit relied on the LIBR method to affirm a bankruptcy court’s refusal to impose a constructive trust on a debtor’s estate.[5] In Stephenson, a third party in a bankruptcy case filed an adversary proceeding against the trustee to recover money that the third party had pledged as collateral to the debtor’s estate. The bankruptcy court concluded that the third party did hold a general unsecured claim in the debtor’s estate for $19 million, but declined to impose a trust in part because the third party could not trace the cash to any property in the estate. The Eighth Circuit affirmed, using the LIBR method on the account where the third party had deposited the $19 million. Since the debtor disbursed more than $19 million on the day the third party made its deposit, the lowest intermediate balance on the account was zero, so there was no property subject to a constructive trust.[6]

The Tenth Circuit also approved the LIBR method in the context of conversion suits.[7] In its prosecution of an unscrupulous attorney, the government relied on the LIBR method to underscore that the attorney had paid himself with proceeds from his client’s improper sale of property that was encumbered by tax liens. When the attorney appealed, claiming the government could not rely on multiple tracing methods in its analysis of a single account, the Tenth Circuit endorsed the use of the LIBR method (as well as the LIFO method) to trace wrongfully converted funds.[8]

U.S. courts have not yet reached a clear consensus regarding what circumstances call for the application of the replenishment rule and those that do not. When the LIBR method is applied without replenishment, “the trustee withdraws non-trust funds first, thus maintaining as much of the trusts funds as possible.”[9] The trust is considered lost as soon as the amount on deposit in the fund containing both tainted and untainted property reaches zero. The Fourth Circuit applied the LIBR method in this manner in Dameron.[10]

At the time of the bankruptcy filing in Dameron, the balance of the debtor’s account was $453,338.47, but the lenders claimed entitlement to a trust exceeding that amount by more than $5,000. The court found that because the account had been reduced below the trust amount, but not depleted entirely, the lenders were entitled to the lowest intermediate balance, without the benefit of any deposits made after that balance was reached.

Conversely, under the replenishment rule, new money landing in an account with tainted funds goes first to replenish the amount of converted funds already expended by the debtor.[11] As the court noted in Mazon, the net effect of applying the replenishment rule in the context of the LIBR method is that once converted money hits an account, future funds landing in the account are presumed to replenish the converted funds, no matter what the source of future deposits.[12]

Pro Rata Distribution

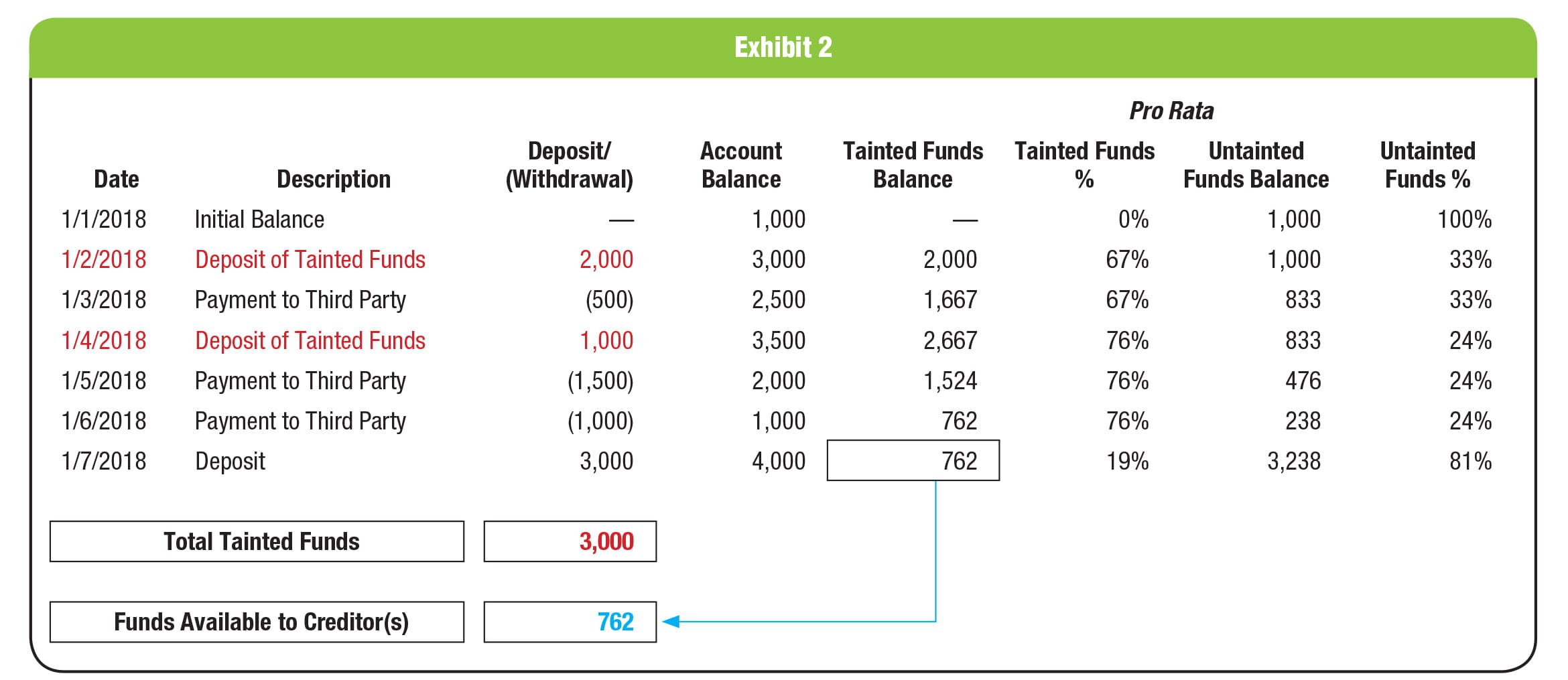

The next method constructs relative percentages of tainted and untainted funds that are then allocated to any subsequent withdrawals. This method is most often utilized when multiple similar creditors seek the same funds. Exhibit 2 provides the same fact pattern as above, but only utilizing the pro rata distribution method. As it demonstrates, the tainted-funds balance is lower when the pro rata distribution method is employed, as compared to both LIBR methods shown in Exhibit 1.

Courts favor the pro rata application of a tracing method where there are multiple similarly situated creditors in the mix, as in a Ponzi scheme where “investors” are being paid with other victims’ deposits.[13] For example, the Seventh Circuit has held that the LIBR method should be applied pro rata where multiple claimants can successfully trace their property back to the same comingled account.[14]

First In, First Out and Last In, First Out

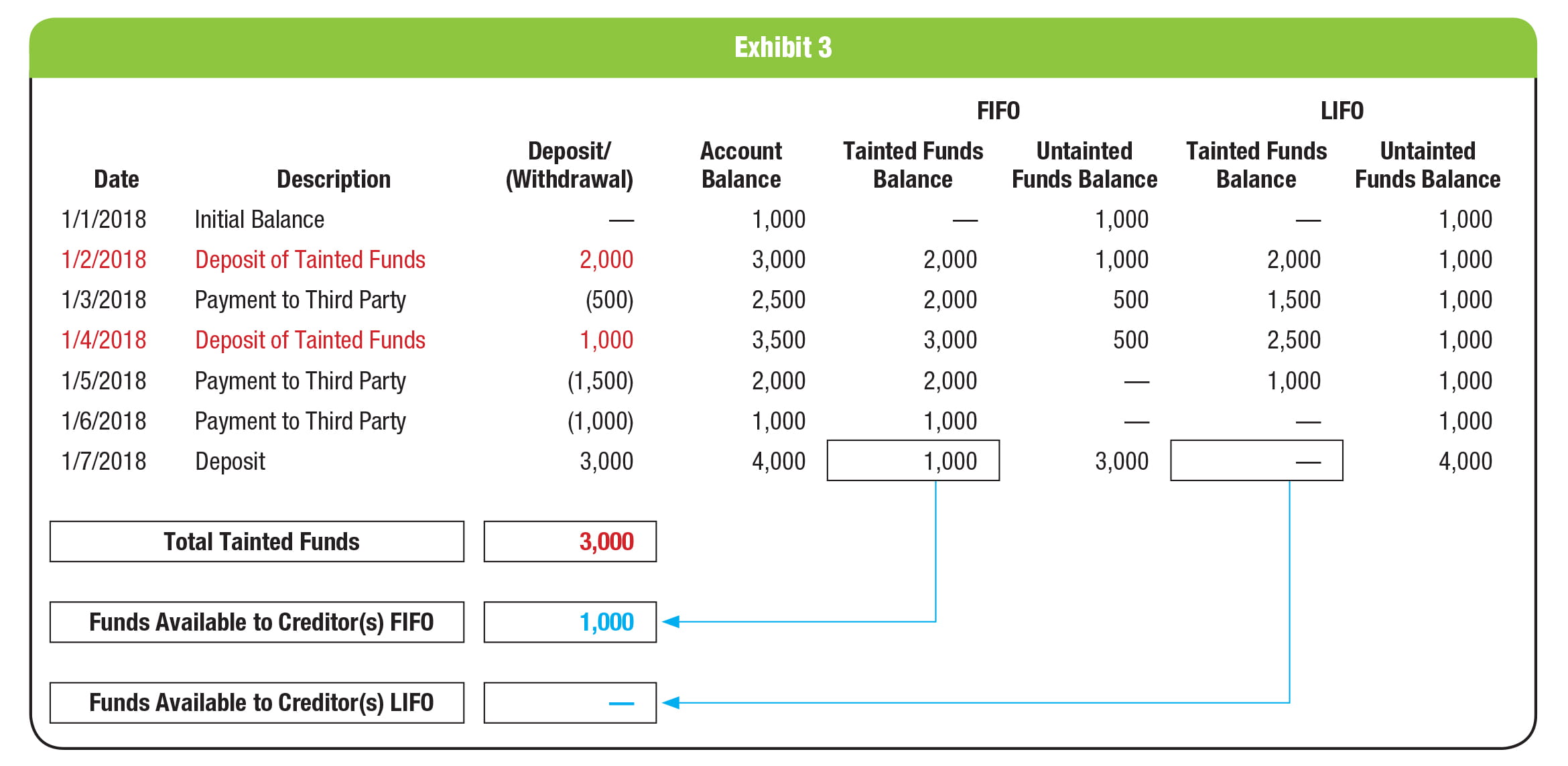

The FIFO method, which presumes the funds are paid out in the order in which they were received, is counterbalanced by the LIFO method, which presumes the funds are paid out by the most recently deposited funds. Exhibit 3 again utilizes the same fact pattern and demonstrates the comparative differences between the FIFO and LIFO methods.

Applying LIFO under this fact pattern results in the tainted-funds balance being drawn down more quickly and ultimately to zero, which does not occur under the other three methodologies. Further, as shown in Exhibits 1 and 3, the funds available to creditors is equal under the stated order of account activity for tracing under both the LIBR method without replenishment and FIFO. Results will vary based on the fact pattern.

Historically, some jurisdictions have applied only FIFO or LIFO, rather than the LIBR method, despite criticism from legal scholars.[15] For example, in 1990, a judge in one of Pennsylvania’s two intermediate appellate state courts noted that, regrettably, Pennsylvania law still required the inflexible application of FIFO.[16] However, such a strict, uncompromising approach to equitable tracing appears to be falling out of favor.

In 2013, the other appellate state court in Pennsylvania noted that the state’s FIFO approach to equitable tracing had been modified so as to include a LIBR-type analysis.[17] In this case, the court endorsed the use of the LIBR method to calculate a creditor’s claim in a debtor’s estate.

Increasing flexibility, like that invoked by the court in Tenco Excavating Inc., appears to characterize some other courts’ approaches to these differing equitable tracing methods as well. In the Henshaw case, the Seventh Circuit endorsed the use of both LIFO and LIBR to trace funds from the same account. The court held that each method constituted an alternative approach available to the government in its attempts to trace wrongfully converted funds.[18]

Conclusion

Courts appear to enjoy a great deal of discretion when it comes to tracing methodologies, but fairness concerns consistently animate different courts’ reasoning. The courts’ commitment to equity in resolving tracing disputes was evident as early as 1924, in the seminal U.S. Supreme Court case involving the mass investment fraud perpetrated by Charles Ponzi.[19] More recently, the Tenth Circuit held that one investor’s invocation of the LIBR method was improper where he did not apply the rule pro rata, and thus artificially elevated his claim over those of the other investors.[20] However, so long as there is an equitable basis for a tracing method, there will be a significant chance of court approval.

- Ruth Welch, a Stanford University law student and summer associate at Cozen O’Connor, also contributed to this article.

- United States v. Henshaw, 388 F.3d 738, 741 (2004).

- Dameron v. Tyler, 155 F.3d 718 (4th Cir. 1998).

- Mazon v. Tardiff, 387 B.R. 641 (M.D. Fla. 2008); In re Mahan & Rowsey Inc., 35 B.R. 898 (1983).

- Ferris, Baker Watts Inc. v. Stephenson, 371 F.3d 397 (2004).

- Id. See also In re Mississippi Valley Livestock Inc., 745 F.3d 299, 308-09 (7th Cir. 2014); Hill v. Kinzler, 275 F.3d 924 (10th Cir. 2001).

- Henshaw at 740-41.

- Id.

- Dameron v. Tyler, 155 F.3d 718, 724 (4th Cir. 1998).

- Id.

- Mazon v. Tardif, 387 B.R. 641 (M.D. Fla. 2008), Hearing Transcript at 69-70.

- Id.

- See, e.g., In re Mississippi Valley Livestock at 308.

- Id.

- Commonwealth Land Title Ins. Co. v. Doe, 395 Pa. Super. 595, 601 (1990).

- Id. at 601.

- Tenco Excavating Inc. v. First Sealord Sur. Inc., 78 A.3d 1181, 1186.

- Henshaw at 741.

- Cunningham v. Brown, 265 U.S. 1 (1924).

- Hill v. Kinzler, 275 F.3d 924 (2001). See also William Stoddard, “Tracing Principles in Revised Article 9 § 9-315(b)(2),” Nev. L.J., Fall 2002, at 135.