Using Forensic Accounting in Trust Disputes

Using Forensic Accounting in Trust Disputes

Introduction

Most people have heard the story of Bernard L. Madoff, the orchestrator of the single largest Ponzi scheme in history, which defrauded thousands of investors of billions of dollars. One of the hallmarks of Madoff’s success in perpetuating the Ponzi scheme rested on his ability to promptly return withdrawal requests to his clients when demanded. The credit crisis induced a large number of Madoff’s clients to become uneasy and, as a result, more of them requested withdrawals than his over-inflated holdings could cover. This led to the confession of the scheme to his sons and his ultimate arrest on December 11, 2008. Madoff has since been sentenced to 150 years in prison while maintaining he acted alone.

Likewise, R. Allen Stanford, the Texas financier, has been accused of a $7 billion Ponzi scheme. The charges against Stanford allege he swindled investors through the sale of bogus certificates of deposit by his Antigua-based Stanford International Bank Ltd. The instruments paid unusually high returns but Stanford has denied the allegations and claims “he had put the depositors’ money into ‘real assets backed up by real investments.’”1 Regardless of the outcome, the collapse of Stanford’s financial empire occurred virtually overnight after the fraud charges were levied against him. Stanford still awaits trial and has recently changed lawyers for the fifth time in an effort to prove his innocence.

These stories represent two of the largest Ponzi schemes uncovered in history and there is anecdotal evidence that fraud cases, large and small, will continue to rise in the near term. A poll conducted by the Institute of Internal Auditors of nearly 300 chief audit executives predicted that fraudulent acts by employees and outsiders have risen since the beginning of the recession.2 In fact, an article from Bloomberg Businessweek argues that fraud is more likely to occur during recessions. The article states that the National White Collar Crime Center has seen an uptick in fraud-related matters around the time of the two most recent recessions.3 The article explains further that “[f]ollowing the savings and loan crisis and the downturn in 1990, white-collar fraud arrests jumped 52% over the next two years; following the Internet bust in 2000, arrests jumped 25% in the following two years.4 There is no reason to suggest the most recent recession will yield different results.

Most fraudulent schemes rely on a similar, underlying trait: the victim’s implicit belief or trust in the architect of the fraud. It is this trust that is the very foundation upon which trusts (i.e., those between a trustee and beneficiary) are built. Given the potential for continued increases in fraudulent activity and the inherent trust placed in trustees, it is of critical importance to become aware of and familiar with the use of forensic accounting in trust disputes. Just as the Madoff and Stanford cases demonstrate, it will take the use of forensic accounting to unravel and ultimately shed light on the ultimate disposition of the investors’ assets. The same can be said for trusts of a substantially smaller size, including family trusts.

Background

A trust is an intentionally created fiduciary relationship with regard to property in which the legal title is in the trustee, but the benefit of ownership is in another person, the beneficiary. In other words, a trust arises when the owner of property separates the benefits from the burdens of ownership by giving them to a different person. Of particular importance though are the fiduciary duties the trust relationship imposes upon the trustee for the benefit of the beneficiary. These fiduciary duties are the life-blood of the relationship but also the linchpin upon which fraudulent activity spawns, cultivates, and matures.

At its most basic level, a fiduciary duty is an obligation to act in the best interest of another party. Inherent in this duty is an expectation that the fiduciary (or trustee) will exercise his or her discretion or expertise in acting for the beneficiary. The fiduciary (or trustee) must exercise all of the skill, care, and diligence at his or her disposal while being held to a high standard of honesty with the added requirement of full disclosure. Finally, the fiduciary (or trustee) cannot obtain a personal benefit at the expense of the beneficiary.

These obligations carry with them a certain weight that the fiduciary must be someone beyond reproach and undoubtedly trustful. Madoff created that trust with his clients as a highly respected, esteemed, and well-established financial expert: “Like so many others who invested with him, his employees weren’t lured to his funds simply by a promise of outsize returns. Rather, they say, they sought the security of investing with a man they knew and trusted. The Bernie they thought they knew.”5 Similarly, Stanford became a well-respected business man with strong ties to politicos within the U.S. as well as the international community: “[t]o David LeBoeuf, a Texas home builder and middle-school buddy, Stanford is ‘a modern-day Howard Hughes, without the weird stuff.’”6 Those we trust implicitly have the ability to inflict the greatest loss.

It is under this umbrella that the use of forensic accounting can be critical to ascertaining whether a trust’s assets are properly managed, sufficiently protected, and ultimately whether the trustee is living up to his, her, or its fiduciary duties.

Forensic Accounting

Merriam Webster defines the term “forensic” as “relating to or dealing with the application of scientific knowledge to legal problems” and is derived from the Latin word forensis, meaning “before the forum.”7 Forensic accounting, therefore, is the specialized application of accounting facts gathered through methods and procedures to help in resolving disputes that eventually may be used in a court of law or similar forum. However, forensic accounting is much different than traditional auditing in a number of ways. First, forensic accountants integrate investigative, auditing, and accounting skills. Second, a forensic accountant reviews data in a critical manner in order to identify patterns of suspicious behavior. Finally, a forensic accountant does not merely rely on statistical probabilities but instead relies upon experience in similar situations, instinct, and finding a workable solution to the problem, not to mention a more detailed and thorough review of all relevant support including documents and electronic data.

In the early 2000’s, as a direct result of the Enron and WorldCom accounting scandals, among others, the accounting profession underwent major changes. Likewise, it saw the emergence of a new breed of accountants colloquially referred to as forensic accountants. The most recent economic downturn created an even higher demand for forensic accountants who possess characteristics above and beyond those of a traditional accountant: highly analytical, detail-oriented and the ability to bring to light the facts that support potential claims in both civil and criminal matters.

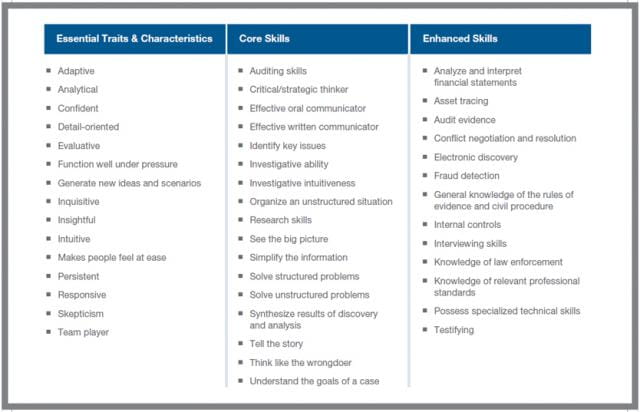

The box on the following page provides a list of the traits, characteristics, and skills of forensic accountants that consumers see as important to the success and effectiveness of their services.8

Forensic accounting can serve any number of distinct goals during a trust dispute. Understanding what a forensic accountant can do, however, is the best place to start. There are three general roles/deliverables where forensic accountants provide assistance during a dispute: 1) discovery assistance (i.e., knowing what specific information to request, and identifying the appropriate individuals to interview or depose); 2) developing a detailed, yet simplified, analysis and report that communicates the appropriate findings and conclusions; and 3) delivering effective testimony whether it be in deposition, trial, arbitration, or other dispute resolution forums.

Outside of the roles outlined above, there are areas of functional expertise. The most traditional expertise associated with a forensic accountant is asset tracing, which can lead to the discovery of asset misappropriation, whether on the part of the trustee or some other third-party in the service of the trustee. The tracing can, and routinely does, involve the reconstruction and analysis of banking and other investments records. This may also require a “sources and uses” of cash analysis, a capital account analysis and substantiation of various other assets including complex financial instruments contained within the trust.

In addition, trust accounting has its own particular rules with respect to proper allocation of receipts and disbursements (i.e., income and expense) and principal. This allocation is critical in determining the maximum amount the trustee is required to distribute to income beneficiaries derived from the trust agreement. If unclear from the trust documents, each state has a form of a Uniform Principal and Income Act that provides guidance on the determination of this allocation.9 This is another area where forensic accountants have been retained to assist in the determination of what receipts and disbursements constitute income or principal since it can impact trust income and the beneficiaries’ rights to distributions. The manipulation of such an allocation, in certain instances where the trustee may be a remainder beneficiary, can potentially be construed as self-dealing. A reconstruction of the financial statements of the trust by the forensic accountant may provide the evidence of a breach of fiduciary duty and at the same time quantify the resulting damages. By way of example, Harry Markopolos, a financial fraud investigator with forensic accounting expertise, all but “gift-wrapped” the Madoff Ponzi scheme to investigators. He has been credited with discovering and documenting the scheme long before Madoff confessed to his crimes.

The above is certainly not an exhaustive list of what a forensic accountant can provide during a trust dispute. However, the case study below proves one example of the use of forensic accounting in a trust dispute.

Case Study

In the late 1990s, attorney John Smith was a rising star in the real estate development industry. He successfully developed and sold thousands of residential units, as well as a number of commercial properties in his young career, that increased his net worth and created a sumptuous lifestyle for himself. Witnessing Smith’s success, he gained the trust of his family, including his parents and siblings, as well as close friends, such that they gave him power to invest their savings and other investments in an attempt to help build their fortunes. In many cases, Smith was appointed as trustee for their living trusts. This afforded Smith the ability to invest large sums of money into real estate ventures and other investments as he deemed appropriate.

When the economy came to a screeching halt in late 2008, Smith was contacted by the beneficiaries of the trusts for which he owed a fiduciary duty. These beneficiaries wanted to know the extent of the negative impact on their investments. However, Smith was nowhere to be found. His luxurious office had been emptied, his cell phone disconnected, and personal residence abandoned. After the initial shock had worn off, many of the trust beneficiaries hired lawyers and forensic accountants to determine the ultimate disposition of their investments. Forensic accountants in the case identified and quantified distributions of cash from various trustee investment accounts as follows:

- Payments directly to Smith above and beyond the normal trustee fees

- Payments to credit cards in the name of Smith for his personal benefit

- Payments to subcontractors for investments held by Smith directly and with no connection to the trust

- Payments to financial institutions for loans made to entities owned by Smith unrelated to the Trust

The amounts distributed from the trust accounts were ultimately deemed to be for the personal benefit of Smith and were recorded in his accounting records as either loans that were later forgiven or reclassified as management fees he “earned” for his role as trustee. The supporting documentation for these transactions were provided in the form of bank wire instructions, cancelled checks, Smith’s personal credit card statements, as well as vendor invoices for unrelated ventures to the trust.

The role of the forensic accountant is to provide the factual data to support claims being made and leave the conclusion of whether the information uncovered rises to the level of fraud, unjust enrichment, and the like to the Trier of Fact. Smith was found and confronted with the above facts. While Smith denied any wrong doing, he was ultimately found guilty of breaching his fiduciary duties and made to pay restitution to his victims.

A recent report published by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners determined that asset misappropriation schemes, those most likely performed by a trustee or a person in a fiduciary role, are by far the most common type of fraud occurring in more than 85% of all reported cases.10 Auditors often refer to the 10-10-80 Rule which states that 10% of employees will never steal, 10% of employees will always steal, and 80% of employees will steal given the right opportunity or justification. The preceding paint a picture of a beneficiary statistically susceptible to fraud, even more so during these trying financial times.

Conclusion

More and more beneficiaries are questioning the returns and administration of their trust property in the current economy, and rightfully so. It is precisely for this reason that beneficiaries should establish a high level of accountability with their trustees and know their options when there are indications of mismanagement. It is not enough to simply “kick the tires.”

Guest author:

Michael N. Kahaian

1 Clifford Krauss, “Stanford Points Fingers in Fraud Case,” The New York Times, April 21, 2009.

2 “Auditors See Increase in Fraud,” Accounting Today, February 5, 2010.

3 Ben Levisohn, “Experts Say Fraud Likely to Rise,” Bloomberg Businessweek, January 9, 2009.

4 Ibid.

5 Julie Creswell and Landon Thomas, Jr., “The Talented Mr. Madoff,” The New York Times, January 25, 2009.

6 Duncan Greenberg, “Crazy for Cricket,” Forbes Magazine, October 6, 2008.

7 “forensic.” Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary, January 5, 2011.

8 Charles Davis, Ramona Farrell, Suzanne Ogilby, “Characteristics and Skills of the Forensic Accountant,” American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, July 27, 2010.

9 Byrle M. Abbin, “Income Taxation of Fiduciaries and Beneficiaries,” 2008.

10 Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse, (Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, 2010), 11.