Selecting Discount Rates for Valuing Early-Stage Intellectual Property

Selecting Discount Rates for Valuing Early-Stage Intellectual Property

The use of rates of return on high-risk investments is common for selecting a discount rate for the implementation of the Income Approach.

Organizations that develop new technologies protected by patents and/or trade secrets have many reasons to determine their values. Valuations may be performed to help raise capital, to facilitate a transaction such as a license or joint venture, to comply with tax regulations or financial reporting requirements, to calculate damages in commercial litigation, or to assist with internal decision making.

Whatever the objective, the valuation process typically considers three common approaches: Cost Approach, Market Approach, and Income Approach. The Income Approach – the only approach that requires the determination of a discount rate – focuses on converting anticipated economic benefits attributable to the asset(s) being valued into a present single amount,[1] using a discount rate consistent with the risk of the anticipated economic benefits.

The valuation of early-stage intellectual property (IP)[2] using an Income Approach is a challenging proposition for several reasons. For instance, it is difficult to project future cash flows for early-stage IP for which there is little or no history of successful monetization or commercialization. The development of a reliable discounted cash flow model requires addressing many difficult questions that have uncertain answers, some of which may include:

- How much investment must be expended to complete technology development?

- Are any governmental approvals required?

- Will the technology be successfully scaled for manufacturing?

- How many units of the relevant products will be sold?

- How much revenue and profit will be earned?

- Will competitors be able to design around the technology, or are noninfringing alternatives available?

Once a reliable cash flow projection is created, the next challenge is selecting an appropriate discount rate for the purpose of converting the future projected cash flows back to a present single amount as of the valuation date. Based on one definition, a discount rate, also known as an opportunity cost, represents the expected rate of return (or yield) that an investor would have to give up by investing in the subject investment instead of available alternative investments that are comparable in terms of risk and other characteristics.[3]

There is an inverse relationship between the discount rate and the present value of future cash flows. In other words, the higher the discount rate, the lower the present value of future cash flows. This is intuitive because, all else being equal, the value of an asset would reasonably be expected to be lower if the risk and uncertainty of the cash flows were higher. Put another way, if an investor perceives a projected cash flow stream for an asset as having a high degree of risk, he or she would be willing to pay a lower price for the asset compared with a comparable asset with a cash flow stream that is deemed as having a low degree of risk, all else being equal.

WACC May Not Be the Answer

When valuing an entire business enterprise, it is common to use a company’s weighted average cost of capital (WACC) to discount future cash flows when implementing an Income Approach. The WACC is determined by calculating the weighted average, at market value, of the cost of all financing sources (both equity and debt) in the business enterprise’s capital structure.[4] In contrast to a discount rate used to value early-stage IP, the WACC represents the overall risk of the business and thus can benefit from the diversification of returns earned on various asset classes, customers, product lines, and technologies. With this in mind, the use of a company’s WACC to value early-stage IP may understate the risk of the cash flows attributable to that IP and therefore overstate the value of the asset.

Intuitively, the risk associated with early-stage IP is generally higher than that for companies with established earnings or more developed product markets. For example, the overall risk of a company (as represented by its WACC) can be thought of as the weighted average risk of all of the company’s assets, some of which may include cash, account receivables, plant and equipment, real estate, and other IP assets. These other IP assets may include patents and trade secrets associated with established technologies, and also well-known corporate and product trademarks. Furthermore, in many cases, the early-stage IP for which a valuation is being performed typically relates to the sale of a single new product line that is expected to generate revenue in the future. In this instance, it is likely that the risk of the IP-related cash flows are more uncertain than the cash flows associated with the entire company. Often, early-stage IP for which a valuation is being performed will be one of the riskier assets owned by the company.

Other Sources to Consider

When discounting cash flows attributable to a company’s financial, tangible, and even certain other low-risk intangible assets, a valuation analyst can use discount rates that are either below or near the company’s WACC. It follows, then, that a company’s riskier early-stage IP would use a discount rate above the WACC. For this reason, valuation analysts will often look to investors’ expected returns on high-risk investments, such as startups or otherwise early-stage companies, to develop discount rates for valuing early-stage IP.

Determining the value of investments that are characterized by unproven technologies and products in undeveloped or unknown markets is by its very nature extremely difficult to do. As an example, venture capital (VC) firms and angel investors typically maintain portfolios of investments in early-stage companies. The risk of these investments is, on average, typically higher than the risk associated with established companies. The companies on which VC and angel investors focus tend to be technology-based and, at an early stage, often derive their value not from the tangible assets employed but rather from the intangible assets developed in the form of patents, trade secrets, and proprietary software. Thus, analysts often look to VC and angel investors’ expected returns to assist in selecting a discount rate for valuing early-stage IP.

We are aware of several sources of information that provide data on actual, expected, or required returns on various types of higher-risk investments at different stages of development and/or with a variety of risk profiles:

- James L. Plummer, QED Report on Venture Capital Financial Analysis, QED Research, Inc., 1987.

- William A. Sahlman and Daniel R Scherlis, “A Method for Valuing High-Risk, Long-Term Investments: The ‘Venture Capital Method,’” Harvard Business School Background Note 288 006, July 1987 (Revised October 2009).

- William A. Sahlman and others, "Financing Entrepreneurial Ventures," Business Fundamentals (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 1998).

- Craig R. Everett, Private Capital Markets Report. Pepperdine University Graziadio School of Business and Management, published annually.

- Richard Razgaitis, Valuation and Dealmaking of Technology-Based Intellectual Property: Principles, Methods, and Tools. Wiley, 2009. p. 271.

Each of the above-referenced sources characterizes relevant investments in a variety of manners. For example, the Pepperdine Private Capital Markets Report provides required rates of return for a variety of different types of investments, including those that are backed by VC firms and angel investors. As explained earlier, we believe that the risk associated with early-stage IP may, in some instances, be similar to the risks of these types of investments. Therefore, it may be appropriate to use the returns on these types of investments found in the Pepperdine report as a discount rate for valuing early-stage IP.

As another example, in their paper titled “A Method for Valuing High-Risk, Long-Term Investments: The ‘Venture Capital Method,’” the authors identify discount rates used by VC firms based on the stage of investment of the company. These stages include seed financing, startup financing, first-stage financing, second-stage financing, and bridge financing. For each stage, the authors describe the purpose of the financing and the characteristics of the company. If the valuation analyst can characterize the risk of the early-stage IP using the same, or similar, stages and related descriptions provided by the authors, he or she may be able to use the related discount rates to apply to the early-stage IP valuation.

As a final example, in his book Valuation and Dealmaking of Technology-Based Intellectual Property: Principles, Methods, and Tools, Richard Razgaitis provides risk-adjusted hurdle rates (RAHRs) that, from his experience, are used by technology investors when investing in or licensing technology that is assumed to be protected by IP. The RAHRs presented by Razgaitis are linked to risk characterizations such as “risk free, very low risk, low risk, moderate risk, high risk, very high risk, and extremely high risk (sometimes known as ‘wildcatting’),” with each characterization described in some level of additional detail. For example, “moderate risk” is described as “making a new product using well-understood technology to a customer segment presently served by other products made by the corporation and with evidence of demand for such a new product.” If the valuation analyst can characterize the risk of the early-stage IP being valued using the descriptions provided by Razgaitis, the related RAHRs may reasonably be used as discount rates to apply to the early-stage IP valuation.

From our experience, and from publicly available books, articles, and other sources of information related to IP valuation, we are aware that valuation analysts regularly use the above-referenced sources to assist with selecting a discount rate to value early-stage IP.

Selecting a Discount Rate

Because a discount rate embodies the risks of the asset(s) being valued and its related cash flow projection, the first step in selecting a discount rate is to identify the relevant risks.

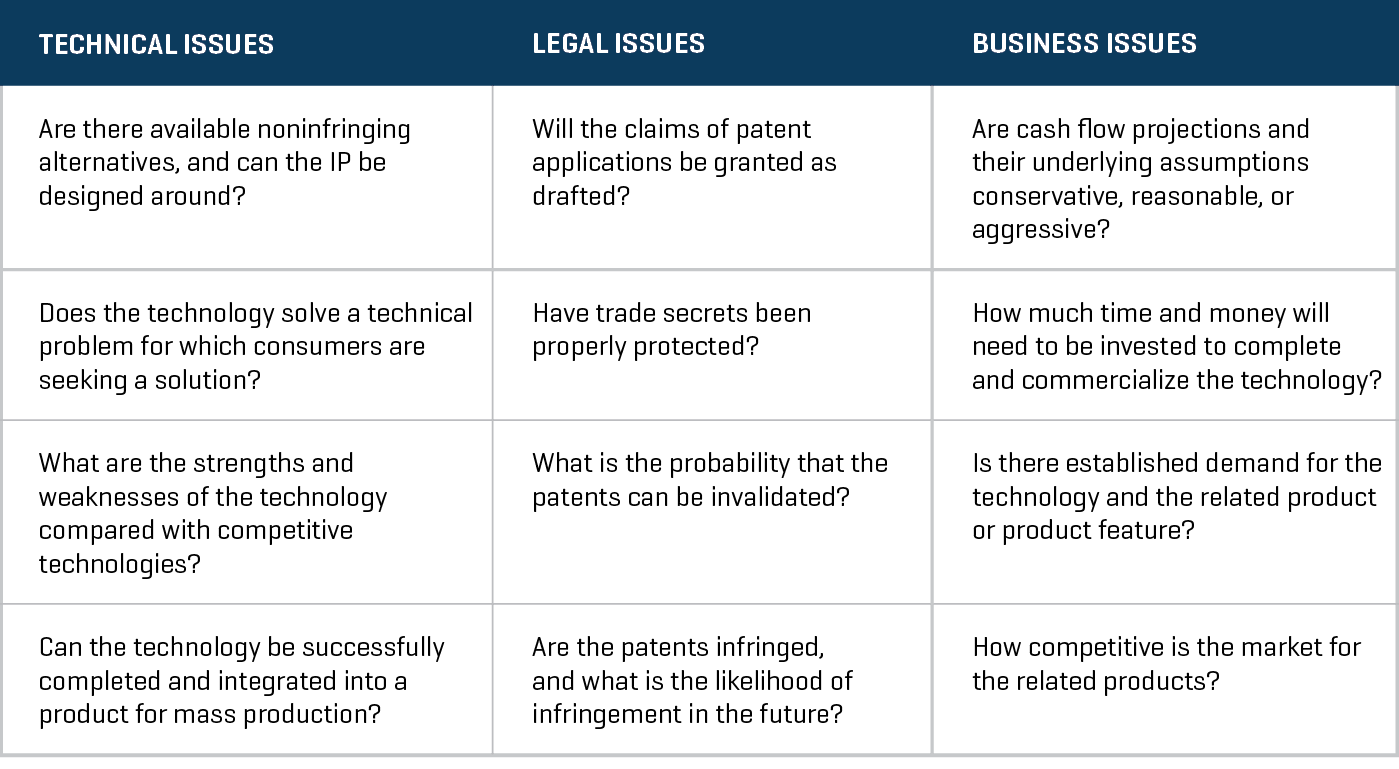

The primary identification of risk as characterized by the various studies referenced earlier relates to the stage of development of the company and/or technology. Additional risks to be considered by the analyst include those related to technical, legal, and business issues associated with the IP being valued. Figure 1 illustrates some issues to consider when identifying risks.

FIGURE 1. Considerations When Identifying Risks

The due diligence process employed during the valuation process should be performed such that it allows the valuation analyst to competently develop solid reasoning around how risk can be characterized in the context of the valuation. This is a key step not only in selecting a discount rate but also in being able to explain or defend the selection of the discount rate.

When ultimately selecting a discount rate to value early-stage IP, the valuation analyst should typically try to understand the company’s WACC, if available, as a starting point. Such information may provide context to the ultimate discount rate determination. The analyst should next look to the various studies identified earlier to determine a range of discount rates that may be applicable to the valuation. The valuation analyst may next be tasked with selecting a single discount rate within the reasonable range of rates identified from the studies. This step requires a significant amount of judgment by the valuation analyst, and, in reality, there is no single correct answer. However, with the due diligence completed, the risk profile developed, and the comparison with available benchmarks made, the valuation analyst should be in a strong position to select and substantiate the final discount rate selection.

- International Glossary of Business Valuation Terms.

- For purposes of this article, “early-stage IP” will be used to describe a situation in which the IP assets being valued relate either to technology that 1) has not yet been commercialized as of the valuation date but is expected to be incorporated into a product in the future or 2) has very recently been incorporated into a product that is being sold as of the valuation date.

- Shannon Pratt and Alina V. Niculita, Valuing a Business: The Analysis and Appraisal of Closely Held companies, 5th ed., New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008.

- International Glossary of Business Valuation Terms.