Readings from the Book of Wisdom: Ex Post versus Ex Ante Damages

Readings from the Book of Wisdom: Ex Post versus Ex Ante Damages

The intent of an award of compensatory damages in many commercial civil litigation matters is to make the plaintiff(s) whole. The damages expert in such matters is often presented with the challenge of developing a damages model that reasonably calculates the plaintiff’s economic position but-for the alleged acts of the defendant. Where projections of “but-for” earnings are involved, as they frequently are in lost earnings or lost profits matters, the methodology of present-value discounting and associated variables and assumptions are frequently the subject of scrutiny, debate, and differences among the experts. One such fundamental difference among experts is the use of ex-post discounting versus ex-ante discounting of the lost profits.

The differences between these two approaches arise as a result of the passage of time between the breach date and the date of analysis (the end date, or date of trial).1 [For purposes of this article, we will define this time period between breach date and trial date as the “Interim Period.”] In simple terms, the two approaches can be summarized as follows:

- Ex Ante Approach – In an ex ante analysis, all damages projected after the date of the breach are present-value discounted back to the breach date to arrive at a damages amount as of that date. Interest is then applied to that amount from the breach date forward to the date of trial to determine a lump sum award as of the date of trial.2

- Ex Post Approach – In an ex post analysis, rather than present-value discounting back to the date of breach, projected damages are instead present-valued to the date of trial. For the portion of damages between the breach date and the trial date (the Interim Period damages), a time-value of money factor is applied forward to the trial date;3 and the projected damages after the trial date (the Post-Interim Period damages) are present-value discounted back to the date of trial.

The treatment of the Interim Period damages is the foremost issue in creating complexity and debate among damages theorists. The debate centers on whether the analyst should rely solely on information known or knowable at the time of the injury versus also relying on information which only becomes available during the interim period. Additional differences between the two approaches include the measurement date and how future damages are discounted.4

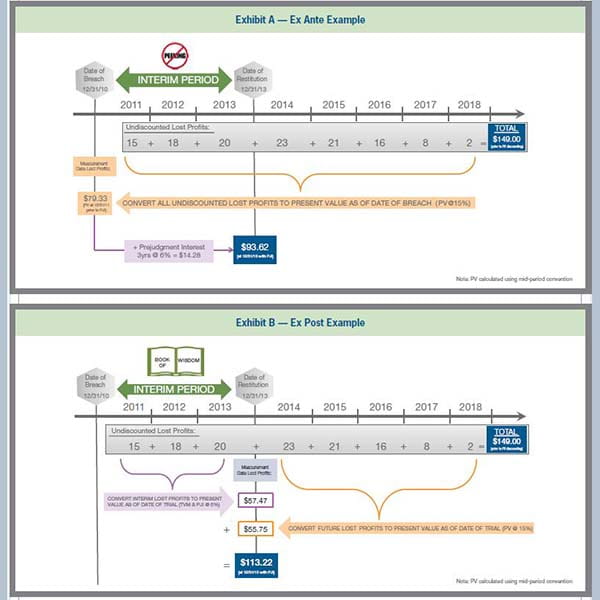

Exhibits A and B highlight the differences between the two approaches. Exhibit A illustrates an ex ante example, and Exhibit B illustrates an ex post example. In both examples, the projection of damages totals $149 over a period of eight years, including three years of Interim Period damages and five years of post-Interim Period damages. Under the ex ante analysis In Exhibit A, all damages after the date of breach are discounted back to the breach date (at a 15% present value discount rate), resulting in total damages of $79.33 as of the measurement date. Prejudgment interest at 6% is applied over the three-year Interim Period, bringing the total damages as of the trial date to $93.62 including prejudgment interest.

In the Exhibit B, Interim Period damages are not discounted back, but rather a time value of money factor is applied forward to the trial date (in this example, the same 6% rate as the ex-ante example’s prejudgment interest rate). Damages after the trial date are present-value discounted back to the date of trial. The result in total damages as of the trial date is $113.22.

The differing results from these two examples illustrate the impact of the application of discounting approach. In this case, even though both examples use the same discount rate (15%) and the same time-value of money/prejudgment interest rate (6%), the ex ante approach produces a nearly 20% lower total damages amount. This difference in result is largely because under the ex ante approach all eight years of projected earnings are discounted for three additional years at 15%, and the impact of the extra present value discounting is only partially offset by the application of 6% prejudgment interest over three years.5 Understanding the factors and considerations behind each approach is critical to defending or critiquing damages analyses employing either approach.

Ex Ante Damages Theory

Applying the ex ante approach to damages analyses, the expert typically only considers information that was known or knowable contemporaneously with the date of injury.6 This approach’s objective is for the analyst to place himself or herself in the shoes of the subject (the plaintiff) as of the valuation date (the date of the breach), and to consider only information known or knowable on that date. The purpose of this perspective is to prepare a projection that only considers that which was reasonably foreseeable at the time of injury, in order to properly model the risks and uncertainties that the plaintiff faced prior to the breach with respect to the projection of hypothetical future “but-for” earnings.7 In its strictest implementation, this approach requires “no peeking” into the future, even though the analyst by the time of trial has the benefit of subsequent knowledge and information that has come to light during the Interim Period. The result is an opinion of damages based on expectations at the time of the breach (e.g., what was the discounted present value of this expected Cash Flow stream on the day of the breach, not knowing what would happen later). Proponents of this approach argue that it correctly values what was lost at the time it was lost and avoids unanticipated windfalls or losses which would become relevant to the plaintiff during the Interim Period. A corollary to this argument is that the ex ante approach appropriately allocates risk between the plaintiff and the defendant, with neither party bearing excess or insufficient risk via the results of the projection and the resulting quantum of damages.

The challenge for an ex ante analysis is that ignoring subsequent information may artificially ignore actual impacts to the plaintiff that, if considered, would result in a more precise estimate of the plaintiff’s loss. This may be particularly apparent in cases where the defendant’s gain is at the expense of the plaintiff, and the expert is analyzing both the plaintiff’s lost profits as well as the defendant’s ill-gotten gains. The defendant’s actual earnings or profits during the Interim Period have a greater degree of certainty than the estimate of the plaintiff’s but-for earnings or profits, and incorporating those amounts as well as the accompanying economic conditions and associated variables may provide a more realistic but-for analysis than employing a strict “no peeking” rule.

Ex Post Damages Theory

In contrast, an expert applying an ex post damages approach typically considers information known and knowable subsequent to the date of injury. If forecasts are used in the damages analysis for future lost profits beyond the trial date, the most recent forecasts are appropriate.8 Any mitigation efforts pursued by the injured party between the date of injury and the date of trial are taken into account.9 This includes the results of mitigation and the costs to mitigate.10

An expert applying an ex post damages approach uses the analysis date or trial date (date of restitution) as the measurement date (rather than the date of breach), as illustrated in Exhibit B.11 Interim Period Cash Flows generated from the date of injury to the date of restitution are considered, and a time-value of money factor is applied to actual and but-for Cash Flows/profits forward to the date of trial.12 In contrast with the ex ante approach’s “expectation” damages, the ex post approach produces damages based, in part, on actual outcomes. In other words, while an ex ante approach attempts to put the plaintiff in the position he or she would have been in on the date of the breach, an ex post approach effectively attempts to put the plaintiff in the position he or she would have been in on the date of trial but-for the actions of the defendant.

Risk and Uncertainty in the Projection and in the Discount Rate

An important related consideration for the damages analyst is the extent of certainty associated with projected Cash Flows. Often, damages analyses require an expert to forecast future expected actual Cash Flows (and estimate future but-for Cash Flows) using contemporaneous information.13 Rarely, if ever, are the estimated Cash Flows assigned 100% certainty. As such, the estimated Cash Flows in damages calculations may be adjusted based upon probability-weighting of the likelihood of the outcome of each year’s Cash Flows. The result is a risk-adjusted stream of Cash Flows (lost profits),14 to which a combination of time-value of money factors are applied forward (prejudgment interest) and/or back (present-value discounted) to the measurement date15 thereby calculating the lump sum present value of the damages.16 Because of the significance of the interplay of risk, uncertainty, and probability, the selection of an ex ante or ex post approach should consider the manner in which these factors have been incorporated into the analysis—either reflected in the projected income stream itself, or reflected in the present-value discount factor. Underlying this can be other considerations of the risk of overly rewarding the plaintiff by eliminating his or her risk; allowing the defendant to reap excess rewards with “unclean hands”; arbitrage theories and who should rightly bear either the risk or the reward, and to what degree. Indeed, any evaluation of the merits of a particular present-value discounting approach requires consideration of the discount rates selected, as well as the extent to which risk and uncertainty are factored into the projected income stream.

Focus on the Interim Period

In evaluating the advantages and disadvantages of an ex ante or ex post approach, the expert should consider the effect of Interim Period events on the plaintiff. For example, did the actual economic events of the Interim Period affect the outcome of the projection risk that the plaintiff faced at the time of the breach? If so, an ex ante approach will not incorporate that effect, and an ex ante approach will differ from an ex post approach. If not, an ex ante approach will likely not be affected by Interim Period events. This does not mean the two approaches would result in identical damages awards. The differences in application of discounting and prejudgment interest would still result in varying damages calculations, as illustrated in the examples at Exhibits A and B.

Suppose the economy was in a downturn during the Interim Period, and a variety of economic factors negatively affected the performance of the plaintiff. An ex ante approach would not consider these factors, and the “no peeking” projection of the hypothetical but-for results of the plaintiff would likely be more optimistic and result in a larger damages amount. An ex post approach would incorporate the actual economic factors that impacted the plaintiff subsequent to the breach. Even so, either approach could be reasonable based upon the facts of the case and the argument of counsel. However, one should carefully consider the conceptual underpinnings of these two approaches when applying them to the facts of each case.

The Book of Wisdom and The Wrongdoer’s Rule

Applying the “Book of Wisdom” concept allows the expert to look past the date of injury and apply facts established in the Interim Period to the damages model. Its origin dates back to 1933 in Sinclair Ref. Co. v. Jenkins Petroleum Co. in which the Supreme Court stated that “Experience is … available to correct uncertain prophecy. Here is a book of wisdom that courts may not neglect. We find no rule of law that sets a clasp upon its pages, and forbids us to look within.”17

Does the incorporation of actual interim economic events result in the plaintiff being either 1) overly shielded from the risk they bore at the date of injury, or 2) overly exposed to the risk that they bore at the date of injury? Application of the Wrongdoer’s Rule, which limits a defendant who has been found liable from assailing the uncertainty of a plaintiff’s damages estimates, allows for the plaintiff to receive the benefit of the doubt and shifts the burden onto the defendant in arguing any uncertainty. In Story Parchment Co. v. Paterson Parchment Paper Co. et al., the Supreme Court ruled that “whatever … uncertainty there may be in [a] mode of estimating damages, it is an uncertainty caused by the defendant’s own wrong act; and justice and sound public policy alike require that he should bear the risk of the uncertainty thus produced.”18

Applying The Book of Wisdom to the Ex Ante/Ex Post Debate

While each approach has relative merits, there is no clear guidance on which is the superior approach, and both have been accepted by the courts. A hybrid approach, incorporating elements of both ex ante and ex post, has also found favor in cases where the expert can support the rationale for his or her use of the particular features of each.

In some cases, such as tortious interference, theft of trade secrets, and other anti-competitive behaviors, the defendant’s actions may harm the plaintiff to the benefit of the defendant either directly or indirectly. Arguments that a plaintiff may be overcompensated via an ex post analysis in these cases may not carry as much weight as if the defendant had not gained at the expense of the plaintiff, such as in breach of contract cases. However, a damages award that returns the plaintiff to its economic position contemporaneous with the date of injury, but leaves the defendant with a gain as a result of its action, may not deter future unlawful acts. Thus, an ex post approach may be appropriate in cases where the defendant has gained as a result of the injury.

The reference to the “Book of Wisdom” should be of particular importance to the damages expert, as it suggests that the consideration of subsequent information should be incorporated with reason. Indeed, present-value discounting requires the careful consideration of approach (ex ante versus ex post); discount rate; risk, uncertainty and probability in the projected income stream; and their integration together in a manner appropriate to the facts and circumstances of the matter at hand.

1 Depending on the situation, the end date may be the expert’s report date, the date of trial, or the date of judgment. For simplicity, I refer herein to trial date as the end date of the expert’s analysis.

2 The applicable interest factor in an ex ante analysis is typically a prejudgment interest rate, which in many state jurisdictions may be set by statute at a fixed or index-based percentage and formula (simple interest versus compounding). Federal courts, however, typically allow greater latitude and tend to follow principles of returning the plaintiff to the position it would have been in if the defendant had compensated it immediately upon injury.

3 Various theories of selecting a time-value of money factor focus on concepts of the damages representing effectively a coerced loan from the plaintiff to the defendant, while the plaintiff has foregone the risk of the projected but-for earnings. Consequently, the time value of money factor to bring interim period damages forward often utilizes either the defendant’s debt rate or the plaintiff’s cost of capital; or some other rate based on the risk of the defendant’s default, or even a simple prejudgment interest rate.

4 Weil, Roman et al., Litigation Services Handbook: The Role of the Financial Expert. 5th edition. (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2012) 5-2.

5 This example uses the same discount rates and time-value of money/prejudgment interest rates in both the ex post and the ex ante illustrations. However, there may be reasons to utilize differing rates under an ex post approach versus an ex ante approach to account for the differences in risk and uncertainty between the two. The subject of deriving an appropriate rate is beyond the scope of this article.

6 Weil, et al., 5-2.

7 Franklin M. Fisher and R. Craig Romaine, Janis Joplin’s Yearbook and the Theory of Damages, Journal of Accounting Auditing and Finance, Volume 5, No. 1, Winter 1990, pp. 145-157.

8 Weil et al. 5-7.

9 Ibid. See also Holzman, Eric. “Battle of the Exes: Understanding the Effect of the Ex Ante and Ex Post Approaches on Damage Calculations.” FVS Consulting Digest (2011) 9.

10 Weil et al. 5-8.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Weil et al. 5-2.

14 Dunn, Robert L. and Everett P. Harry. “Modeling and Discounting Future Damages.” Journal of Accountancy Online (2002) 3.

15 Per the United States Court of Federal Claims “To prevent unjust enrichment of the plaintiff, the damages that would have arisen after the date of judgment (‘future lost profits’) must be

discounted” (Pratt and Grabowski 102).

16 It should be noted that some experts forego calculating risk adjusted lost profits in favor of applying a higher discount rate designed to incorporate the same risks that would have otherwise been included in a risk adjusted lost profits analysis. See Dunn and Harry 3-8 for further discussions regarding the relative tradeoffs of this approach.

17 Sinclair Ref. Co. v. Jenkins Petroleum Co., 289 U.S. 689, 698-99, 53 S. Ct. 736, 77 L. Ed. 1449 (1933).

18 Weil et al. 5-13.