Dealing With Commodity Price Fluctuations

Dealing With Commodity Price Fluctuations

Global Demand Drives Price Fluctuations

Commodity prices have been in the news since 2007 when the economy was overheating and the demand for all raw materials far outweighed supply. The continued climb of commodity prices led many to believe that we were not experiencing a bubble, but rather a long-term shift in commodity prices driven by a growing proportion of the world population adopting Western-style consumption habits that left raw materials in permanent short supply. Despite a challenging year for commodity prices in 2012, the general premise behind long-term demand for raw materials remains intact.

The unprecedented drop in demand that occurred in late 2008 left many companies fighting other battles not directly related to commodity prices. Some managers wondered if commodity pricing was an addressable issue, and if it was, how could it be dealt with? Since then, however, commodity prices have continued on a volatile pace, which has led to the creation of numerous hedging strategies and products.

The cause of commodity price fluctuations is rooted in the development of a world market that is not yet adept in anticipating global fluctuations in demand. Price fluctuations are actually being exacerbated by the availability of information and the speed of communication. One may think that better information would reduce volatility, so this result seems counterintuitive. When commodity markets were more localized in nature, market participants had a much better feel for demand levels. This proximity to supply and demand factors allowed prices to follow more predictable patterns. However, the fact remains that the global market has been permanently opened, and this, in turn, has caused tremendous volatility. The unpredictability of price levels has led developing countries that understand their own long-term raw material shortages to enter and exit markets as prices reach certain levels. This activity, while it has increased the frequency of price movements, has actually decreased volatility in the sense of dampening highs and lows. Thus, while market participants see more frequent price movements, the end result is actually a certain level of price stability (i.e., move movements but within a narrower band), which lends itself well to hedging activity.

Supply chains that have not needed to worry as much about the volatility of input prices historically have made price fluctuations the responsibility of the supply chain participant best capable of dealing with them. For example, the initial response to commodity price volatility from automotive OEMs was to push the risk onto suppliers. (The other solution was to pass along the risk to the end consumer. It’s not likely that your average car buyer would feel comfortable with a scrap surcharge as they sit at the car dealership trying to get financing to buy a car!) In the end, the automotive supply base could not deal with the risk as effectively as the OEMs. The steel buying program created by the OEMs has allowed suppliers to focus on simply manufacturing products instead of trying to anticipate potential movements in steel prices when developing their (typical) five-year program pricing. Accordingly, raw material price volatility issues in the automotive industry have begun to abate as OEMs take on more commodity risk. Boeing has implemented similar procurement programs for its suppliers. Other industries will need to follow suit.

The first response by the investment community to the increased volatility of historically “stable” commodities was to create countless new derivative products that would provide raw material consumers with the ability to hedge their commodity risk. The new commodity contracts that have become available are primarily focused on ferrous materials, which include scrap metal, hot rolled steel coil, and steel billets. Many of these contracts will become more useful as liquidity improves due to greater trading volume. Many of these products are somewhat complicated to deal with, or represent imperfect hedges at best. Addressing the specific correlations of the derivative products relative to published commodity prices or how to structure the hedging is outside the scope of this article. However, suffice it to say, under GAAP accounting, a hedging instrument must reach a minimum threshold of 80% correlation to the underlying asset in order to qualify for hedge accounting treatment.

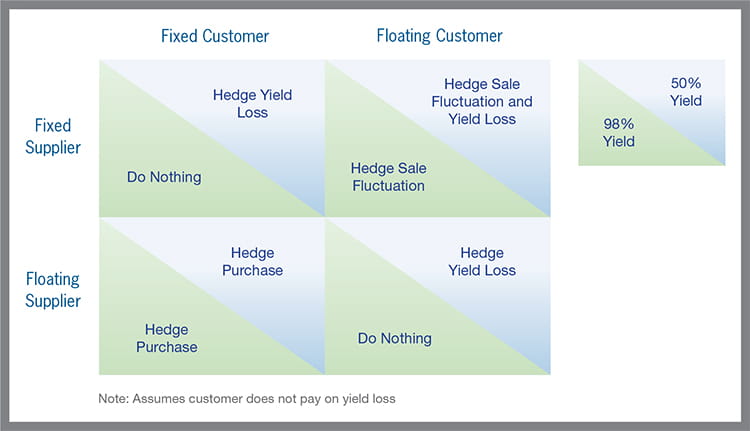

That leaves the most important question for any member of a supply chain: Should I be “hedging?” The quotation marksare used to emphasize that hedging commodity risk does not necessarily mean buying financial instruments on the London Metals Exchange or with the CME Group. We have developed a simplified chart to decide whether a company should consider hedging commodity risks. In several cases, the commodity risk may not be worth hedging or, more importantly, there may be a more cost-effective way of managing the risk.

The chart below provides a preliminary analysis on dealing with commodity risks.

The top of the chart depicts the way your customer buys from you: Either they are buying on a fixed price basis or a floating price basis (where such floating price is tied to your price of raw material input). The left-hand side of the chart depicts how you buy raw material from your suppliers: Either you can fix your purchase price or you are required to accept a floating price based on spot commodity prices. Each quadrant of the chart has a diagonal line that separates the response to price fluctuations. The lighter portion to the upper right provides the correct response assuming a low manufacturing yield (we have arbitrarily chosen 50% to make the point) and the lower left provides the solution if your manufacturing yield is quite high (we have chosen 98% to illustrate).

Example: A metal stamper has two different customers requesting two different products. Customer A is requesting a perfectly square stamped part that the stamper can produce with only a 2% scrap rate. Customer B is requesting a round part with hole cutouts that will result in a 50% scrap rate.

If Customer A will agree to a guaranteed price and the stamper can fix his raw material price from his supplier, there is no need for the stamper to hedge either its exposure to Customer A or the price it will get for its scrap. Both are known at time of pricing and thus can be built into the cost and revenue estimate.

However, Customer B will not agree to a fixed price, but would rather pay based upon whatever the market is for that particular product at the time of delivery. In this case, the stamper may want to protect itself against adverse changes in both the price Customer B will pay and what it will be able to sell its scrap for post-production, depending in part upon the time period between quote and delivery.

If the solution is to hedge, a small manufacturer need not open up a trading account with a brokerage firm. Many trading companies exist to provide solutions to hedging issues on a smaller scale, taking upon themselves (for a fee) the commodity price risk for small manufacturers. Using an outside trading company can be more expensive than hedging the exposure yourself, but the benefit can be greater flexibility and peace of mind that an experienced partner is handling the market transactions.

This chart provides a possible framework to hedge exposure in a typical manufacturing process. Each situation need to be analyzed independently. For example, manufacturers of products made with precious metals often do not even own the inventory in the manufacturing process. It is common for gold product producers to lease the material or borrow the metal from a commodity trading lending institution and purchase it upon shipment to their customer when the market price is set by the current trading price. They do not need to concern themselves with the cost of the raw material, except for how it affects demand.

Commodity price fluctuations are not going away anytime soon and volatility will likely increase before settling down. The issue of dealing with raw material cost volatility should not be ignored or passively accepted. Managing inventory and raw material price risk will be an important part of maintaining a healthy business for years to come.