Assessing the Fairness of PE Fund Transfers

Assessing the Fairness of PE Fund Transfers

The related-party nature of private equity fund-to-fund transfers drives the need for fairness opinions on these transactions.

When economic conditions turn south, private equity (PE) portfolios may take a hit. Not only can the value of the underlying companies decrease, but it also becomes more difficult to exit a business. Given these headwinds, PE firms might consider transferring assets from one of their funds to another, which may necessitate a fairness opinion.

Private equity firms generally raise funds from limited partners (LPs) to make controlling-interest investments in private companies. The stages of PE funds are fundraising, investment period, and harvest period. Firms set up multiple funds, and once the investment period for a particular fund nears its end, the harvest period for that fund begins and the fundraising process for the next fund starts. Funds often have a 10-year life with the option of two additional oneyear extensions. The investment period is typically the first five years, and the harvest period is the next five years, or an extended period if needed.

The general partners (GPs) of PE firms anticipate an investment holding period of approximately four to six years for each portfolio-company investment of the fund. That being said, holding periods of less than one year do occur, as do much longer holding periods with investments still being held at the end of the legal life of the fund. For example, the market downturn in 2002 and related bursting of the Internet bubble caused liquidity issues for private equity limited partners, as GPs had limited realizations due to poor market conditions. This generally caused PE holding periods to increase, which did not please many limited partners. Some large institutional limited partners (insurance companies, pension funds, etc.) began to package their PE holdings to sell to secondary investors at a discount to achieve liquidity. Others attempted, with limited success, to securitize their private equity portfolios and issue investment-grade bonds along with tranches of sub-investment-grade to avoid the discount required by other investors. Funds with vintage years of 2005 to 2007 have been experiencing similar issues as high premiums were paid for prefinancial crisis investments that have not performed up to expectations and have yet to be realized. These events have shown that the timing of a PE portfolio company’s liquidity event is far from certain.

Different circumstances can arise with PE fund holdings in which portfolio companies of different funds of the same PE firm may enter into transactions with one another, or one fund may seek to acquire another fund’s interest in a portfolio company. These transactions may drive the need to obtain a related-party fairness opinion.

Drivers

Situations that can drive the need for a related-party fairness opinion can include:

- A PE fund may be at the end of its legal life but still holds an investment. The GP would like to close down the fund to save on administrative costs. It may make financial sense for 1) a later-vintage fund to purchase the investment, or 2) a portfolio company of the latervintage fund to purchase it; or 3) the GP may purchase it to close the fund.

- A portfolio company held in a fund that has no more investable capital available may enter into an acquisition. To fund the equity portion of the acquisition, the PE sponsor may look to a later-vintage fund with uncalled capital to provide equity for the transaction. The fully invested fund and the later-vintage fund may have limited partner investor groups that are not identical.

- A portfolio company of a PE fund may enter into an agreement (e.g., management services) with another portfolio company of the sponsor that is held in a different fund, and the funds do not have identical investor bases.

The above situations give rise to a related-party transaction, and it is in the best interests of the GP to obtain a fairness opinion if the investor groups differ between the funds. The GP will want to obtain an opinion for each fund to evaluate the fairness to the “sell side” as well as the “buy side.” These fairness opinions should be completed by two separate, independent financial advisors to ensure that each side is treated fairly in the transaction.

Approach and Analysis

The approach to the preparation of a related-party fairness opinion involving a business enterprise is no different from that of an unrelated-party opinion. From a valuation perspective, the income and market approaches would be applicable. Stand-alone financial projections are appropriate to value the subject company. These projections would be used in the preparation of a discounted cash flow analysis. Under the market approach, guideline publicly traded companies would be selected to develop applicable valuation multiples, e.g., enterprise value to EBITDA. In addition, M&A transactions of businesses in the same or similar industries would be researched to develop applicable multiples.

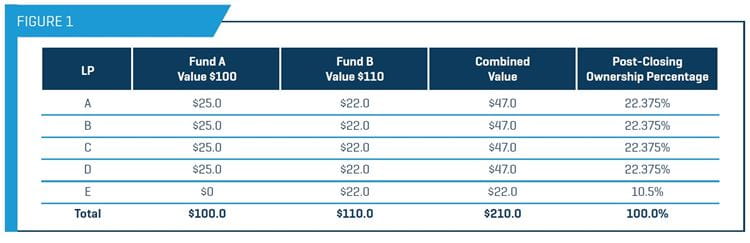

To show where things might become a bit more complicated and to demonstrate the need for an experienced financial advisor to assist, take the case illustrated in the first bullet point in the “Drivers” section, in which an existing portfolio company held in a fund that is at the end of its legal life (Fund A) will be purchased by a portfolio company in a later-vintage fund that has uncalled capital (Fund B) in order to close out Fund A. If the existing Fund B company has a standalone value of $100 and is acquiring the Fund A company for $100, this would imply that ownership would be allocated among the investor bases of the two funds on a 50%/50% basis and allocated accordingly to the LPs. However, in addition to the $100 price for the Fund A acquisition, let’s assume there are expected synergies of $10, and as such, going forward the company on a combined basis is worth $210.

Let’s assume the limited partnership interests are as follows:

As reflected above, LPs A, B, C, and D have interests in both funds, and LP E is the additional investor in Fund B. If independent financial advisors have been retained to issue an opinion to the investors of Fund A or Fund B as to the fairness of the post-transaction ownership structure and related value, the allocation of the synergies between Fund A and Fund B must be assessed.

The company owned by Fund B can realize operating synergies in the acquisition. Upon due diligence, it is determined that it is reasonable to allocate all the synergies to Fund B. This would result in the post-closing ownership split, as shown in Figure 1.

Based on Figure 1, if you were the financial advisor issuing the fairness opinion for Fund A, the LPs of Fund A (LPs A–D) should have ownership of the new combined company, which will now be held in Fund B, of 22.375% each. From the perspective of the Fund B investor (LP E) that is not involved in Fund A, a fair level of ownership would be 10.5%.

Benchmarks

The issuance of a fairness opinion for a related-party agreement among a single PE sponsor’s portfolio companies that are held in two separate funds has its own challenges. Information on the terms of other, similar agreements are generally private and not available. This makes comparing the terms of one related-party agreement to the terms of another market agreement entered into among unrelated parties at arm’s length difficult at best and impossible at worst. As such, depending on which side of the transaction the financial advisor is on, that advisor can look at other benchmarks to help assess the reasonableness and fairness of the terms.

For example, the following factors can be reviewed to aid in the analysis of the fairness of a related-party agreement:

If the agreement involves a real estate lease, market data is generally available to help assess the terms of the subject agreement.

If the agreement involves management services, the financial advisor can estimate what it would cost the paying company if such services were to be provided in-house. The financial advisor could also review the expected costs compared with the payments (revenue) to be received by the company providing the services in order to assess its profit margin, which can then be compared with the margins of publicly traded companies that provide similar services.

If the agreement involves certain manufacturing functions, the financial advisor can evaluate the paying company against the historical costs it has incurred on its own in performing such functions. Alternatively, the paying company may have other plant locations that may continue to perform the functions, and those costs can be used as benchmarks in the due diligence process. The financial advisor could also review the expected costs compared with the payments (revenue) to be received by the company providing these functions to assess its profit margin, which can then (again) be compared with the margins of publicly traded companies that provide similar manufacturing functions.

The Value of an Independent Opinion

Related-party fairness opinions for transactions involving portfolio companies of PE sponsors have the same challenges as unrelated-party opinions, but with some potential additional complications. Each situation will have its own unique set of circumstances that will need to be analyzed and addressed by the financial advisors to ensure that the parties to the transaction are each being treated fairly. In the end, the PE firm and the boards of the respective portfolio companies will be fulfilling their fiduciary duties to their limited partners and shareholders, respectively, by hiring a qualified advisor to provide an independent and well-thought-out opinion to support the subject transaction.