M&A Facilitators: The Value of Earnouts

M&A Facilitators: The Value of Earnouts

Introduction

As the direction of the economy remains uncertain after the extreme volatility experienced over the past two years, corporate development and financial sponsor professionals may find earnouts and other forms of contingent consideration, such as clawbacks, to be effective tools to facilitate mergers and acquisitions (M&A). Employing an earnout, which generally represents additional payments in a deal that are contingent upon the achievement of future events, serves as an extremely useful tool to facilitate the consummation of transactions; sellers feel they are receiving appropriate value for their business and are able to participate in upside subsequent to closing, while buyers feel they are protected from overpaying and share performance risk with the seller.

The increasingly complex structures of contingent consideration as well as the changed financial reporting landscape, as a result of the issuance of Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) Topic 805, Business Combinations (FASB ASC 805), have created measurement challenges for financial reporting and audit and valuation professionals. Under FASB ASC 805, contingent consideration is required to be measured at fair value and recognized at the acquisition date as part of the purchase consideration.1 Pursuant to FASB ASC 805-10-20, contingent consideration is defined as either:

An obligation of the acquirer to transfer additional assets or equity interests to the former owners of an acquiree as part of the exchange for control of the acquiree if specified future events occur or conditions are met. (earnout)

or

The right to the return of previously transferred consideration if specified conditions are met. (clawback)

Deal Structures

Earnouts are commonly employed as a form of purchase consideration in deal structures when material uncertainties exist with respect to the target’s performance subsequent to closing. Purchase consideration contingent on achieving a desired outcome aides in “closing the gap” in the valuation expectations of buyers and sellers and is dependent on the analysis of risk from the perspective of the counterparties in a negotiated transaction. Therefore, the structure of earnouts can vary widely and is generally customized to each transaction.

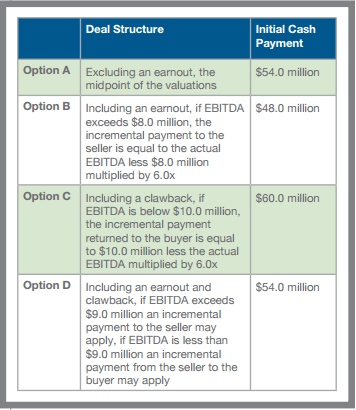

For example, consider a potential deal where industry multiples are deemed to be 6.0x earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA). The owners of the target company estimate its EBITDA, inclusive of various add-backs, to be $10.0 million. However, given the aggressive nature of the add-backs and the uncertainty that the target can maintain recent-period results, the buyer estimates the target’s EBITDA to be $8.0 million. Based on the industry multiple and absent any earnout or clawback provisions, the target prices the deal at $60.0 million, while the buyer prices the deal at $48.0 million. The following table illustrates potential deal structures to overcome this impasse:

While option A represents a compromise between the counterparties, it is limited in that the buyer is accepting increased risk related to overpayment and the seller is likely feeling undercompensated. Options B through D present more progressive purchase structures that better align the risk and return prerogatives of the buyer and seller.

Common components of earnout structures that will vary for each set of circumstances include:

- Financial thresholds (e.g., level of sales, gross margin, or EBITDA hurdles);

- Milestones (e.g., Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, product launch, stage of development completion, retention of a customer for a set period of time);

- Market performance hurdles (e.g., stock price internal rate of return tiers);

- Length of the term of the earnout period;

- Single period or clawback/cumulative features; and

- Capped or unlimited payments.

To further illustrate the potential for risk mitigation, the majority of purchase consideration for a deal involving a start-up enterprise may be structured to be contingent upon the achievement of future performance metrics. In contrast, a buyer may be more comfortable paying up-front for a mature target with an established market for its products or services and a history of consistent financial performance. Additionally, certain industries may be better candidates for using earnouts as a form of purchase consideration, particularly industries with evolving product innovation such as biotechnology, information technology, and pharmaceutical. For instance, in the pharmaceutical industry, it is common for purchase consideration to be contingent upon the approval of certain products in the research and development (R&D) pipeline. This structure protects the buyer from overpaying for a product not yet approved for sale and allows the seller the ability to participate in upside post-transaction, while providing incentive for the seller to remain committed to ensuring the product ultimately receives regulatory approval.

Accounting Treatment

Regardless of the structure, an understanding of the accounting treatment of contingent consideration is paramount for reporting entities given the significant balance sheet and income statement ramifications. As outlined in FASB ASC 805-30-25-5, the acquirer shall recognize the acquisition-date fair value of contingent consideration as part of the consideration transferred in exchange for the acquiree. Moreover, FASB ASC 805-30-25-6 provides that contingent consideration must be classified as an asset if the contingency is a clawback. If the contingency is an earnout, it must be classified as a liability if the settlement of the liability is tied to the issuance of a variable number of shares of common stock or is settled in cash. If the earnout is to be settled by a fixed number of shares, it is classified as equity. Because the asset or liability is required to be recognized at fair value, the amount initially recorded on the opening balance sheet will typically not tie to the amount specified in the purchase agreement.

The balance sheet classification of contingent consideration, as outlined in FASB ASC 805-30-35-1, determines whether it must be re-measured at each reporting period subsequent to initial recognition. Contingent consideration classified as equity does not require re-measurement and settlement is accounted for within the equity account. Contingent consideration classified as an asset or liability requires re-measurement at fair value at each reporting date until the contingency is extinguished. In this circumstance, changes in fair value are recognized on the income statement as a gain or loss.2

The accounting treatment for earnouts to many is counterintuitive. If the acquiree meets the performance hurdle, the acquirer must satisfy the earnout and likely incur an additional expense.3 In other words, if the initial measurement is less than the actual payment, a loss is recorded on the income statement (even though the business is actually performing better than expected). Whereas the failure to meet the performance threshold would result in income recognition as the liability is written off. In other words, if the initial measurement is greater than the actual payment, a gain is recorded on the income statement (even though the business is actually performing worse than expected). This treatment results in increased balance sheet and income statement volatility versus the prior standards. As a consequence, many reporting entities choose to prepare purchase price allocations contemporaneously with a potential transaction. This allows increased visibility as it pertains to future earnings-per-share ramifications for accretion/dilution modeling.

While it may appear that the accounting treatment provides an incentive for reporting entities to recognize a higher fair value measurement for earnouts through the potential to record a subsequent gain on the income statement if the earnout is not paid because of underperformance of the target, the countermeasures are the potential adverse impact on debt covenants (as the earnout may be considered a debt-like instrument if it is settled in cash or a variable number of shares) and the fact that any goodwill recorded as a result of the initial fair value measurement of the earnout will remain on the acquirer’s balance sheet even if no earnout payments are made. This could lead to goodwill impairment implications as an over-measurement in the fair value of an earnout will result in a greater amount of goodwill on the balance sheet than is supported by the financial performance of the target.

Valuation Methods

While plain-vanilla earnouts may be measured through a straightforward discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis, complexly structured earnouts may require more sophisticated methods, such as a probability weighted DCF analysis, Monte Carlo simulations, or an option approach. These methods are best applied to earnouts with financial or performance thresholds. Earnouts with milestone contingencies often require the implementation of real options analysis. Ultimately, the method applied should be based on the terms and provisions of the contingent consideration and best capture the economic conditions of the earnout structure.

1. Discounted Cash Flow Analysis

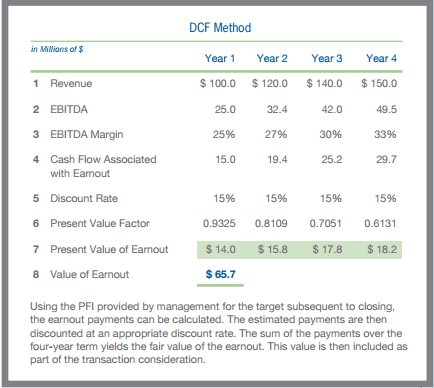

When measuring an earnout using a DCF analysis, the target’s prospective financial information (PFI) is forecasted and analyzed over the term of the earnout.4 The analyst compares the PFI to the financial targets of the earnout to determine the expected payments and associated timing, which are then discounted to a present-value equivalent as of the acquisition date. Despite the simplicity of this approach, it is limited to the analysis of a single scenario and is not well suited to capture the economics of cliff or tiered targets. For example, a DCF analysis may yield a zero value for an earnout where payment is made only if sales exceed $30 million, where the PFI sales are $29 million. This result does not reflect the fact that PFI should capture probability-weighted sales, where there is likely a non-zero probability that sales would exceed $30 million and trigger an earnout payment.

The following example highlights the application of a DCF analysis to measure an earnout with a four-year term and a structure that pays the seller 60% of EBITDA.

2. Probability-Based or Scenario Methods

When the volatility of PFI is great or where contingent payments are based on future events that will result in vastly different cash flows for the target, analyzing probability-weighted outcomes may be the most applicable method to measure the contingency. This form of scenario analysis is commonly referred to as the Probability-Weighted Expected Return Method (PWERM). PWERM estimates value based upon an analysis of various future outcomes.5 Under this method, concluded value is based upon the probability-weighted present values of expected future results, considering each of the possible outcomes available to the target. This method is more robust than the DCF analysis in regard to future outcomes; however, disadvantages include the inherent difficulty in projecting the timing and occurrence of future events, as well as the associated cash flows.

3. Monte Carlo Methods

Traditional DCF analysis has limitations with respect to the array of potential outcomes. Therefore, it may be beneficial to analyze a Monte Carlo simulation. A Monte Carlo simulation, which is a system that uses random numbers to measure possible outcomes and the likelihood of occurrence, allows an analyst to contemplate numerous outcomes related to future company performance that is not considered when analyzing deterministic PFI. In applying this method, assumptions must be made regarding the range of likely growth rates and earnings margins, as well as inputs related to minimum and maximum payouts under the earnout terms. Although these assumptions are incremental to a deterministic DCF analysis, the Monte Carlo simulation can provide useful insight, such as the expected value of the earnout, the range of potential earnout payments, and the frequency of earnout payments. Despite its benefits, Monte Carlo simulations are challenging to audit, and therefore, may be best applied to supplement or test the reasonableness of the results from application of a DCF or scenario analysis.

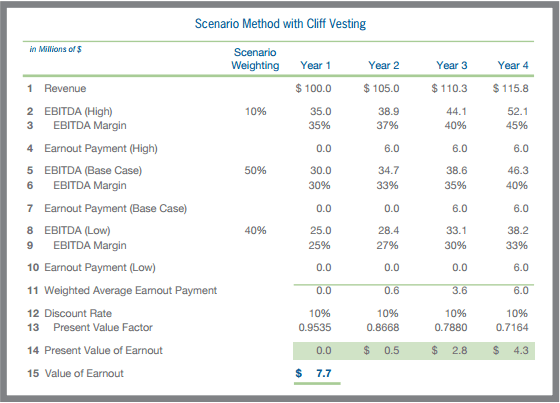

The example below illustrates two methods to value an earnout with cliff vesting and a four-year term. The subject earnout is structured such that a payment of $6 million is required in any year where EBITDA exceeds $37 million.

As presented, three scenarios of PFI were estimated. After determining if an earnout payment is triggered in each year for each scenario, the payments are weighted by the likelihood of occurrence. The probability weighted payments are then discounted to a present-value equivalent as of the measurement date.

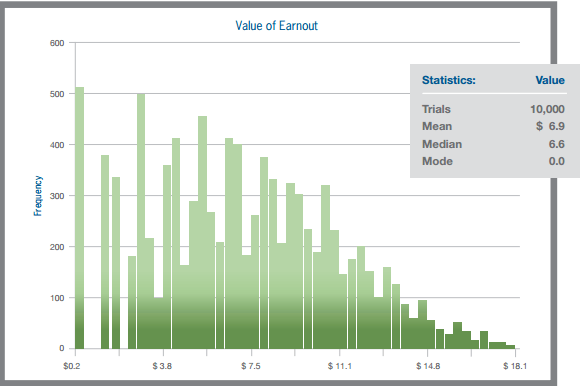

In addition to the probability-weighted DCF scenario analysis, a Monte Carlo simulation is employed. The Monte Carlo simulation analyzes thousands of scenarios to determine the most likely earnout payment.

Based on the projected base case revenue in years one through four, the following assumptions were employed:

- Annual revenue growth ranging from negative 10% to positive 10%, with the most likely scenario being 5%; and

- EBITDA margins ranging between 25% and 45% of revenue, with the high expectation at 45% of revenue, the low expectation at 25% of revenue, and the base case increasing from 30% to 40% of revenue.

The simulation software applies the range of assumptions to calculate thousands of possible future EBITDA levels and corresponding values for the earnout. Moreover, the simulation software produces a probability distribution of the outcomes (as illustrated in the chart above) as well as confidence intervals related to projected EBITDA and a median and mean expected value for the earnout. These results can be used to conclude on a fair value measurement or as support for the fair value measurement derived from application of the DCF scenario analysis or other approaches.

4. Option Methods

Because an earnout essentially represents a call option on the future performance of a target, option pricing models such as the Black-Scholes Option Pricing Model (Black-Scholes Model) or a lattice model may be employed to measure fair value. The Black-Scholes Model calculates the price of a traditional call option by analyzing the volatility and opportunity cost of investing in the underlying asset. A lattice model utilizes a “pricing tree” whereby future movement in a target variable is estimated based on a volatility factor. In each time period, the model assumes that at least two movements are possible (up or down). The lattice represents the evolution in the value of the target variable. In the case of an earnout, the strike price would be equal to the earnout hurdle (e.g., a tiered level of sales) and the underlying asset would represent acquisition date asset value (i.e., the trailing 12 months sales prior to the acquisition date).

Correspondingly, the economic nature of milestone earnout structures (e.g., payments contingent on FDA approval) may be best captured through application of real options. Real options, which represent the right, but not the obligation, to take action at a predetermined cost for a predetermined period of time, recognize that today’s investments give investors future choices. If conditions are favorable, further investment will be pursued. If conditions are unfavorable or have deteriorated, the original investment may be abandoned. Real options are complex to implement and

require significant supporting documentation related to future events and the decisions and financial outcomes contingent upon those events.

Discount Rates

After selecting the appropriate method, an applicable discount rate must be estimated to convert the future contingent payments to a present-value equivalent as of the measurement date. There is a wide spectrum of potential discount rates to be employed to capture the risk associated with earnouts and clawbacks. The ultimate conclusion requires a detailed analysis of the factors that influence the subject earnout’s measurement and credit risk.

The earnout or cash flow volatility is the key driver to analyze in the determination of an applicable discount rate. The lowest possible rate that could apply in order to capture the time value of money is a risk-free rate of return. However, because credit risk applies for even AAA-rated acquirers, the cost of debt adjusted for the acquirer’s credit risk may be most applicable for an earnout with highly certain payments. In other words, if there is close to a 100% probability that the earnout will be paid, the economics of the structure essentially represent financing a portion of the transaction consideration with debt.

On the other end of the spectrum, highly uncertain earnouts, such as those associated with in-process research and development projects, may require discount rates that approximate venture capital rates of return. For earnouts structured as a sharing ratio of EBITDA between the buyer and seller, the overall business risk or weighted average cost of capital may be the most applicable discount rate. Finally, it is important to consider the fact that an applied scenario analysis may quantify measurement risk. In this circumstance, it may not be appropriate to incorporate additional risk over-and-above an adjusted credit risk in the application of a discount rate to the probability-weighted earnout payments.

Conclusion

By understanding the applicable valuation methods and subsequent accounting treatment of earnouts, reporting entities can more effectively structure purchase agreements and better identify and disclose the long-term financial statement ramifications of these instruments. While it may appear that the accounting treatment provides an incentive for reporting entities to recognize a higher fair value measurement for earnouts through the potential to record a subsequent gain on the income statement if the earnout is not paid because of underperformance of the target, the countermeasures are the potential adverse impact on debt covenants and the fact that any goodwill recorded as a result of the initial fair value measurement of the earnout will remain on the acquirer’s balance sheet even if no earnout payments are made. This could lead to goodwill impairment implications as an over-measurement in the fair value of an earnout will result in a greater amount of goodwill on the balance sheet than is supported by the financial performance of the target.

1 It should be noted that the new guidance did not change the accounting treatment with respect to earnouts tied to future services, which are required to be expensed. Under prior guidance (SFAS 141), contingent consideration was generally recognized as incurred and resulted in an increase to goodwill.

2 The FASB regulations also allow for modifications to the fair value measurement based on new information related to the facts and circumstances of the contingency that existed at the acquisition date that were identified after that date, but not longer than one year subsequent to the acquisition date. Such changes are defined as measurement period adjustments and do not impact the income statement.

3 The potential for additional expense results from the inconsistency between the amounts recorded at initial measurement at the acquisition date and the actual payment (even if the estimated payment exactly matches the actual payment) because of the use of present value factors in measuring fair value.

4 It is important to note that the PFI used to value the earnout may differ from the cash flows utilized to value the assets acquired in a transaction. Specifically, the PFI used to measure the assets acquired should reflect market-participant assumptions, while the PFI used to measure the earnout should reflect buyer-specific assumptions.