Oil & Gas Valuation and the Impact of Income Taxes

Oil & Gas Valuation and the Impact of Income Taxes

We take a historical look at how income taxes, or lack thereof, influence the valuation of oil and gas properties, and also what the new tax bill means for E&Ps.

There is much deliberation about the role of income taxes in oil and gas asset valuation. The decision to burden (or not burden) future cash flows with income taxes would seem to materially impact the valuation conclusion.

Some believe strongly that oil and gas valuation must be done on an after-income-tax basis. These professionals are following the logic that income taxes are a real expense and therefore should be considered in any valid analysis. They also contend that valuation measures derived from publicly traded guideline companies (often taxable C corporations) should be properly matched with after-income-tax cash flows of the subject asset. Other professionals, particularly those active in the oil and gas property marketplace (the acquisitions and divestitures (A&D) market), tell us that they rarely model income taxes in their internal valuations because the income tax situation of potential buyers varies widely.

They say that the prospective buyer could include a C corporation that pays corporate income taxes or a pass-through entity that passes allocated income and losses to its owners. Thus, these professionals tend to apply before-income-tax (pretax) discount rates to pretax cash flows to develop valuations. We have seen numerous oil and gas property valuations – performed by sophisticated investment bankers, valuation firms, and petroleum engineers – that do not specifically consider income taxes.[1]

How can these differences of opinion, which would seem to result in materially different valuation conclusions, exist among valuation experts? Can these views be reconciled? We believe they can, and we will take a further look at the following:

- Property- or asset-level valuation, rather than entity-level valuation

- Working interest (or leasehold) valuation

- The discounted cash flow (DCF) method of valuation[2]

The income-tax-paying status of the assumed buyer can dictate how income taxes should be treated in the valuation analysis. If the expected buyer is ExxonMobil, then income taxes probably should be considered in the analysis as we show later. In contrast, if the expected buyer is a private equity-backed exploration and production (E&P) company organized as an income tax pass-through limited liability company (LLC) or limited partnership (LP), then income taxes may not have an impact on how the E&P company values the target asset.

This is because the A&D team buying the asset recognizes that the income-tax-paying status of their shareholder base (to which the income tax burden is passing through) can differ widely, from nontaxable public pensions to individuals taxed at the highest personal income tax rates. A one-size-fits-all income tax assumption does not work. In addition, property attributes are key in considering whether income taxes are material to a valuation analysis. Due to expensing of intangible drilling costs (IDCs), properties with high expected development costs typically have little to no taxable income for many years, and, therefore, income tax has little impact on the valuation.

Thus, the A&D marketplace, in which properties transact and where the exit price is ultimately determined, works primarily with pretax cash flows and pretax discount rates for valuation purposes. Real estate appraisers employ the same logic and do not project income taxes in their DCF valuation work.

Valuation Methodology

The traditional after-income-tax valuation methodology is based on the assumption that the likely buyer of an oil and gas asset is a C corporation (which pays federal and state income taxes at the entity level), such as an integrated[3] company (e.g., ExxonMobil or Chevron) or a major independent[4] (e.g., ConocoPhillips or Devon).

Field-level cash flows for producing and nonproducing properties, as appropriate, are projected for the subject asset typically based on a petroleum engineering analysis. Corporate office general and administrative expenses are likely deducted, then cash income taxes are projected and deducted from the cash flow stream. The cash income tax projections will assume a full step up in basis to fair value, and the unique tax benefits of IDCs (and recently revised, under the Trump tax reform, bonus depreciation on tangible assets) and depletion deductions, if applicable, will be modeled. Other tax assumptions[5] may also be considered in the valuation model.

The resulting taxable income is generally much lower than reported income, which gives rise to the often large deferred tax liabilities on seasoned C corporations’ balance sheets.

The resulting after-tax cash flow projection is then discounted to present value based on the buyer’s or public peer group’s weighted average cost of capital (WACC) to calculate an implied value of the subject asset. The WACC (or, in practice, the after-income-tax cash flows) must be appropriately risk adjusted so there is a proper matching of the risk of the subject asset cash flows with the assumptions embedded in the WACC. In our experience, there are numerous considerations in the WACC, and these considerations often vary among buyers, with certain buyers adjusting their WACC to consider items like their own cost of capital and internal A&D hurdle rates (which may vary significantly from public companies’ required returns), operational and development risks, and tax considerations.[6]

Has the World Changed Since the Traditional After-Tax Model Became the Standard?

In the past, the integrated and major independents were the dominant players in the A&D market. In contrast, there are now many more oil and gas property buyers that are not income-taxpaying entities. Private equity has spawned hundreds of private E&P companies in the past 20 years that are large players in the A&D market. The corporate form of these entities is almost always an LLC or LP, which are pass-through entities for federal income tax purposes. Public upstream master limited partnerships (MLPs), which are also pass-through entities, were very active buyers in the A&D market until 2015 and 2016, when many fi led for bankruptcy protection.

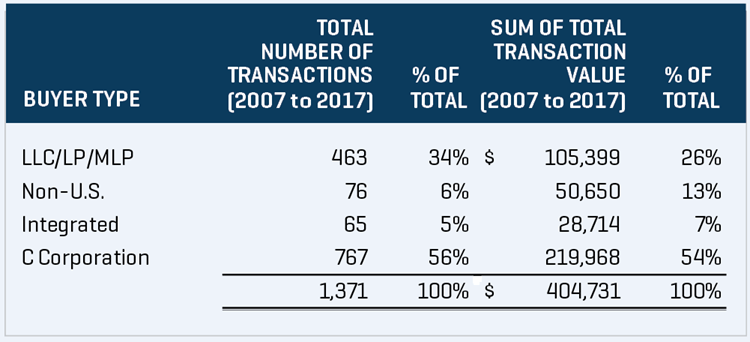

We looked back 11 years[7] for all transactions between $10 million and $10 billion in the A&D market with a single identified buyer to categorize the buyer’s income-tax-paying status. We found 1,371 transactions representing a cumulative total transaction value of $404.7 billion,[8] with an average and median deal size of $295 million and $105 million, respectively. As shown in Figure 1, we generally found that about 55% of the buyers were U.S. C corporations; 25% to 35% were LLCs, LPs, or MLPs; 5% to 15% were non-U.S. buyers; and only 5% were integrated oil companies, such as ExxonMobil.

FIGURE 1. Upstream Asset Sales of U.S. Properties ($ IN MILLIONS)

Source: IHS Connect From January 1, 2017, to December 31, 2017

Excluding transactions involving multiple or undisclosed buyers

Thus, in 25% to 35% of the transactions, buyers are pass-through, non-income-tax-paying entities which vary in their consideration of the income tax burden when acquiring a property. Furthermore, most of the publicly traded C corporations are paying almost no income taxes, as we will discuss later, and we question whether even these buyers explicitly consider income taxes when acquiring a property.

Cash Tax Rates of Publicly Traded Integrated and E&P C Corporations

In a November 6, 2017, Raymond James research report, analyst Pavel Molchanov stated that only a few (certain large-cap companies) of the E&P companies covered by Raymond James currently pay federal income tax, even though they book a provision for income tax expense on their financial statements. When asked to comment on the effects of Trump tax reform on E&P companies, Molchanov said, “Corporate income tax matters less for energy than just about any other sector of the U.S. economy.”

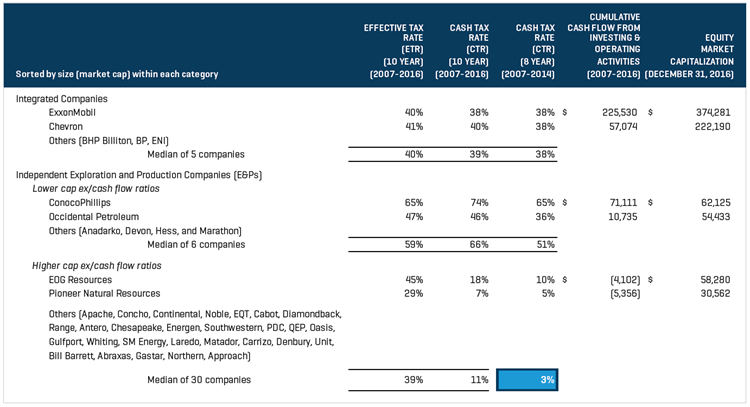

Using the S&P Capital IQ database for each company in our data set,[9] we examined the cash income tax paid and the reported income tax (provision for income taxes) for each company. We then compared these two figures with each company’s earnings before tax (EBT) to calculate the tax rates shown in Figure 2. We will refer to the former ratio as the cash tax rate (CTR) and the latter ratio as the effective tax rate (ETR). It is the cash income tax paid or CTR that is relevant for valuation purposes in a DCF method, not the reported income tax expense or ETR. We calculated these figures on a cumulative[10] basis during the 10 years ending in fiscal 2016 and the eight years ending in fiscal 2014.[11]

FIGURE 2. Analysis of Cash and Effective Tax Rates of Publicly Traded Oil and Gas C Corporations ($ IN MILLIONS)

Source: S&P Capital IQ, SEC Forms 10-K and 20-F

Cumulative data for fiscal years noted

As expected, the median 10-year CTR and ETR for integrated companies was about 40% (the combination of the 35% federal statutory rate and other local and foreign jurisdictional income tax rates). We believe the CTR and ETR are nearly the same for the integrated companies because federal income tax rules limit the benefits of IDC and depletion for them.[12] The integrated firms also have significant exposure to foreign operations and foreign taxes as well as profits from refining and retail sales of petroleum products.

We then grouped the publicly traded independent E&P companies by their level of capital expenditure activity relative to cash flow. The CTRs are generally high for the companies with relatively lower capital spending ratios, but we acknowledge that the data for the lower-spending companies is murkier. Numerous factors are influencing the data for such companies other than a lack of IDC benefits, including reorganizations, unusually large asset impairments, and foreign operations.

Most of the independent C corporations (30 companies) had high capital spending ratios and very low CTRs. Based on the cumulative 10-year period ending in fiscal 2016 (12 observations), the median 10-year CTR for the group was just 11%. Based on the cumulative eight-year period ending in 2014 which is more relevant (29 observations), the median eight-year CTR for the group was shockingly low at just 3%. Seven of the companies – those with very active drilling programs – effectively paid no federal cash income taxes during the cumulative eight-year period.[13]

Trump Tax Reform

So what impact will President Trump’s tax reform, commonly referred to as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, signed into law on December 22, 2017, have on valuation? The CTRs for the integrated companies will decline, enabling those companies to be more competitive oil and gas property buyers based on their lower costs of capital. Clearly, their equity became more valuable with the reduction in the corporate statutory income tax rate from 35% to 21% and the repeal of the corporate AMT. Because there were no major changes for IDC and depletion rules with the new law, we don’t expect any major changes in the CTRs for the companies that are heavily reinvesting cash flows. Tangible oil and gas property will now have the benefit of a full or near-full expensing of capital expenditures for a number of years.

Overall, we think the new tax law is slightly positive for oil and gas property valuation.

What Moves the Valuation Needle?

So what should oil and gas investors and valuation advisors take away from this information? It does not appear appropriate to assume that C corporation income taxes are relevant in every oil and gas asset valuation because C corporations are not the only buyers in the A&D market. Even after the demise of upstream MLPs, private equity-backed LLCs and LPs will continue to be active participants in the A&D market.

If the CTRs of many of the pure-play E&P companies, which are often used in asset valuation because they have a single basin focus, are extraordinarily low as shown herein, then pretax and after-income-tax cash flows and WACCs for these E&P companies are not very different, particularly for properties with high development levels.

It now makes sense why such divergent views can exist between oil and gas valuation professionals with regard to the income tax issue. If the likely buyer is an integrated or major independent, then income taxes may be a material aspect of the valuation. If one is valuing a property where the likely buyer is a tax pass-through entity, then explicit income tax considerations may not be appropriate to the valuation. (Mineral and royalty property buyers are almost always income-tax pass-through entities; we have never seen such buyers model income taxes in their valuation models.)

The major valuation needle movers will continue to be assumptions regarding developmental drilling pace, well type curves, and major operating and drilling costs, not income tax assumptions. Our experience and discussions with the top A&D advisory firms confirm this observation.

Use of the Market Approach, in addition to the DCF method, can clear confusion and add important corroborating evidence in the valuation exercise because this approach implicitly captures income tax (and other) assumptions, to the extent such assumptions are relevant.

The authors thank John Bradford, Shishir Khetan, Loretta Cross, and Matt Barnes for their valuable contributions to this article.

- In the June 2015 Survey of Parameters Used in Property Evaluation, published by the Society of Petroleum Evaluation Engineers, 90% of the 89 respondents said they do not consider income taxes in their valuation analysis. That is, they apply pretax discount rates to pretax cash flows.

- The Market Approach to valuation implicitly considers income taxes. For example, Delaware Basin acreage that transacted at $35,000 per net acre inherently incorporated the buyer’s assumed income tax (and other) assumptions in establishing the purchase price, to the extent such assumptions are relevant.

- The term integrated is a U.S. federal income tax designation and generally means the company is vertically integrated and includes refining operations. Typically, integrated companies do not have the same tax advantages as nonintegrated companies.

- The term independent typically means the company is not integrated.

- The alternative minimum tax (AMT) (under the pre-Trump tax reform structure but no longer applicable in 2018) and specific state income tax projections may or may not be considered based on the depth of analysis.

- While no entity-level tax is imposed on pass-throughs, we have observed the spectrum of tax treatment in property acquisitions by these entities, including the inclusion of discrete tax adjustments in the cash flows to applying pretax required rates of returns to pretax cash flows.

- From January 1, 2007, to December 31, 2017, using the IHS Connect upstream asset transaction database.

- Including nondisclosed buyers and properties bought by multiple entities, the total was 1,806 deals and $509 billion in total transaction value.

- Our data set consists of all publicly traded E&P companies in SIC 1311 with reported market caps in excess of $100 million as of December 31, 2016, and certain of the largest asset buyers listed for our study for Figure 1. We also required that a company have positive cumulative EBT from fiscal 2007 to 2016 and that the company report cash taxes paid and EBT for at least nine years prior to fiscal 2016 to be included in the study.

- We used a long-term cumulative approach to capture the cyclical highs and lows of the upstream oil and gas industry and capture the effect of a company using tax losses to reach back into prior years for refunds.

- It was important to also consider the eight years ending in fiscal 2014 to eliminate the anomalies caused by large impairments taken in 2015 and 2016 related to the major decline in oil prices beginning in late 2014.

- During this time period, federal income tax rules allowed only 70% of domestic IDC of an integrated company to be expensed per year. Generally, IDC incurred outside the U.S. does not receive any special benefits, such as a tax acceleration deduction. Generally, integrated oil companies do not qualify for the special tax benefits of percentage depletion.

- The federal income tax rules to incentivize the reinvestment of cash flow from operations back into drilling and exploration activities have succeeded from a public policy perspective. Generally, these smaller, nimble E&P companies were the industry pioneers that used the latest technology to unlock vast U.S. hydrocarbon resources over these past 20 years and enabled the U.S. to approach North American energy independence – an inconceivable prospect even less than 10 years ago.